Scientific American Celebrates 180 Years with Stories of Scientific U-turns

In honor of SciAm’s 180th birthday, we’re spotlighting the biggest “wait, what?” moments in science history.

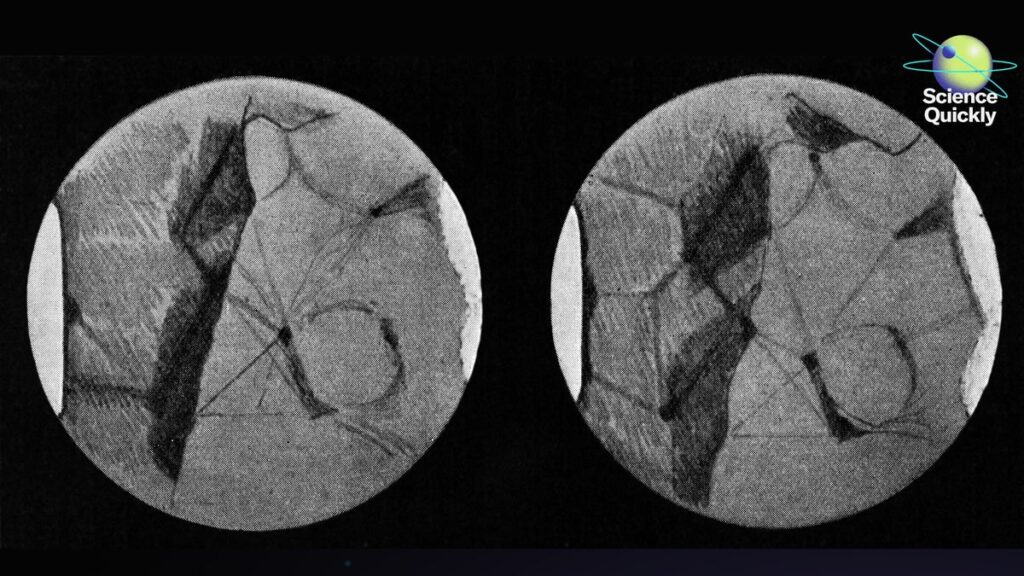

Drawings of Mars showing its ‘canals’ and polar ice caps in drawings created from observations made at the Lowell Observatory in 1907.

Photo by Ann Ronan Pictures/Print Collector/Getty Images

Rachel Feltman: Happy Monday, listeners! For Scientific American’s Science Quickly, I’m Rachel Feltman.

Today we’re doing something a little different from our usual weekly news roundup. Scientific American turns 180 this year, and we recently celebrated with a collection of print features about times in history when science has seemingly done a complete pivot—a 180-degree turn, if you will. We thought it would be fun to take you on a tour of a few highlights from that package.

First up, we have a story from freelance health and life sciences journalist Diana Kwon about nerve regeneration. For millennia doctors and scientists believed that any damage to the nerve cells that carry signals throughout the body must be irreversible. While many instances of nerve damage are, indeed, difficult to treat, scientists have realized over the past couple of centuries that nerves can and do regenerate.

On supporting science journalism

If you’re enjoying this article, consider supporting our award-winning journalism by subscribing. By purchasing a subscription you are helping to ensure the future of impactful stories about the discoveries and ideas shaping our world today.

Throughout this evolution in our understanding of nerves it was still widely believed that neurons within the central nervous system, composed of the brain and spinal cord,were incapable of healing. Now we know that even these most precious neurons can regenerate under the right conditions.

As research continues into exactly which mechanisms encourage (or block) neural regeneration throughout the body, scientists are also engaged in another debate: whether human brains are capable of producing new neurons throughout adulthood. The phenomenon of adult neurogenesis would have been unfathomable mere decades ago, but a growing body of evidence now supports it. Just imagine what secrets we’ll have uncovered about the nervous system 180 years from now.

In another example of a scientific turnabout, Scientific American senior features editor Jen Schwartz reminds readers that plastic was, ironically, invented as a sustainable alternative to another material: ivory. In fact, back in 1864 Scientific American published news of a contest from billiard-table manufacturing company Phelan & Collender seeking an alternative for vanishing elephant tusks, which, at the time, were used to make pool balls. The company offered $10,000 as a reward for this feat of materials science.

A printer from Albany, New York, named John Wesley Hyatt came up with celluloid in response, though he chose to patent the invention for himself rather than accepting the prize money. His celluloid billiard ball has been called “the founding object of the plastics industry.” Unfortunately, as Jen’s article for SciAm explains, while the demand for ivory in the billiard industry dropped with the introduction of celluloid, elephants were still targeted for their tusks for other products. And as we now know the invention of plastic radically changed the way we produce and consume goods—and not always for the better.

In another scientific 180, detailed by Scientific American contributing editor Sarah Scoles, we learn how the search for alien life has periodically been turned on its head. (So maybe multiple 180s?)

In the late 19th century an Italian astronomer observed groovelike markings on Mars, which convinced an American astronomer that the Red Planet hosted a whole civilization. In 1906 that second astronomer, Percival Lowell, wrote a book positing that Martians had carved out a sophisticated network of watery canals. Even when a closer look at Mars in 1909 revealed that those canal-like markings had actually been an optical illusion, Lowell’s theories persisted. In 1916 a Scientific American managing editor wrote in New York Times letters to the editor that he still believed Mars held sophisticated life and an irrigation system to prove it. Of course, when the Mariner 4 spacecraft gave us our first flyby view of Mars in 1965, we saw our planetary neighbor for the desolate world it is.

While we’re unlikely to do another 180 on the existence of intelligent life in our solar system anytime soon, scientists have recently become aware of the abundant potential opportunities for microbial life in our cosmic backyard and beyond. We may not be peering up at Mars hoping to see aliens traveling around by gondola anymore, but in some ways the hunt for alien life is more optimistic than ever.

Those are just a few of the 180-degree pivots you can learn about in the latest issue of Scientific American. Check out our 180th-anniversary issue on newsstands, or go to ScientificAmerican.com for more fascinating stories of scientific swerves. We’ll have additional anniversary treats popping up online in the next few weeks, too, so stay tuned.

If you want to help us celebrate our birthday, join our #SciAmInTheWild photo challenge by September 5. Just snap a pic of any Scientific American print issue in a setting that reflects or complements the cover theme. Then share it on social media using #SciAmInTheWild. Make sure to tag Scientific American, and include your name and location. Or if you prefer to stay off social media, email your photo to contests@sciam.com. You could win a one-year Unlimited subscription, plus a bundle of awesome gadgets and gear. Terms and conditions apply. You can find the official rules at SciAm.com/180contest.

That’s all for today’s episode. We’ll be back on Wednesday to explore one of the most intriguing mysteries of the deep sea: the phenomenon known as “dark oxygen.” And on Friday, we’re reflecting on another major historical milestone: the 20th anniversary of Hurricane Katrina. Our usual science news roundup will be back next week.

Science Quickly is produced by me, Rachel Feltman, along with Fonda Mwangi, Kelso Harper and Jeff DelViscio. This episode was edited by Alex Sugiura. Shayna Posses and Aaron Shattuck fact-check our show. Our theme music was composed by Dominic Smith. Subscribe to Scientific American for more up-to-date and in-depth science news.

For Scientific American, this is Rachel Feltman. Have a great week!

It’s Time to Stand Up for Science

If you enjoyed this article, I’d like to ask for your support. Scientific American has served as an advocate for science and industry for 180 years, and right now may be the most critical moment in that two-century history.

I’ve been a Scientific American subscriber since I was 12 years old, and it helped shape the way I look at the world. SciAm always educates and delights me, and inspires a sense of awe for our vast, beautiful universe. I hope it does that for you, too.

If you subscribe to Scientific American, you help ensure that our coverage is centered on meaningful research and discovery; that we have the resources to report on the decisions that threaten labs across the U.S.; and that we support both budding and working scientists at a time when the value of science itself too often goes unrecognized.

In return, you get essential news, captivating podcasts, brilliant infographics, can’t-miss newsletters, must-watch videos, challenging games, and the science world’s best writing and reporting.

There has never been a more important time for us to stand up and show why science matters. I hope you’ll support us in that mission.