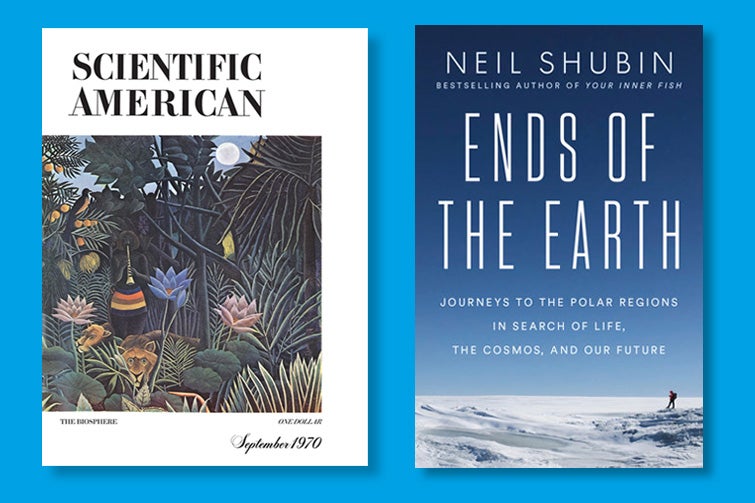

Selecting a book to read can sometimes be overwhelming: countless books are published every year, and there are countless more published years ago that we haven’t gotten around to. If you’d like to incorporate some science books into your TBR (to-be-read) list, Scientific American has been reviewing books for well more than 100 years. Below is a collection of some of our favorite (and sometimes downright snarky) book reviews over the past century. We’ve paired each title with a recently published book on the same topic that a modern-day reader might enjoy. Maybe you read this book from 2025 or that book from the 1930s. Either way, the past 100 years of science writing are a treasure trove.

Health

On supporting science journalism

If you’re enjoying this article, consider supporting our award-winning journalism by subscribing. By purchasing a subscription you are helping to ensure the future of impactful stories about the discoveries and ideas shaping our world today.

Tuberculosis: Its Cause, Prevention, and Care by Frank H. Livingston

Macmillan, 1930

Everything Is Tuberculosis

by John Green

Crash Course Books, 2025

In March 1931 Scientific American reviewed Frank H. Livingston’s 1930 book Tuberculosis 12 years before a cure for the eponymous disease was found. We noted that the book had a “layman” author and said “although entirely non-professional we recommend it highly for its common sense and helpful spirit”— pretty high praise from us back then! Published in March 2025, author John Green’s latest book, Everything Is Tuberculosis, arrived at a vastly different historical moment:tuberculosis cures are readily available. Though he’s a “nonprofessional” as well, Green’s commonsense view illuminates how inequity in treatment around the world allows the disease to persist.

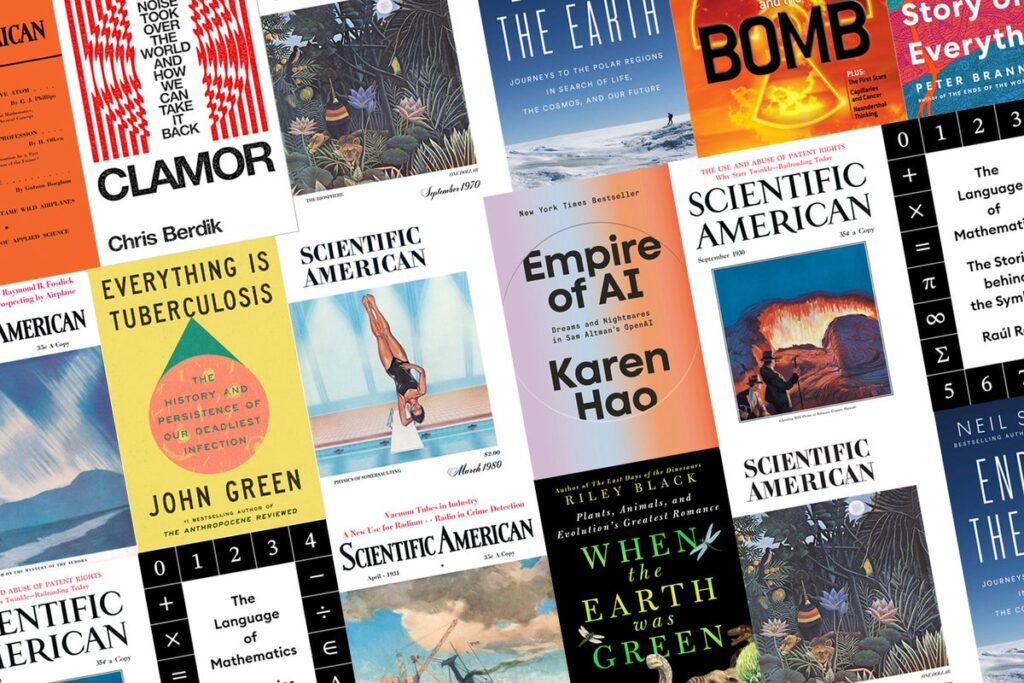

Your Hearing: How to Preserve and Aid It

by W. C. Phillips and H. G. Rowell

D. Appleton and Company, 1932

Clamor: How Noise Took Over the World—And How We Can Take It Back

by Chris Berdik

W. W. Norton, 2025

In January 1933 Scientific American reviewers found W. C. Phillips and H. G. Rowell to be two “outstanding authorities” on human hearing. Their 1932 book Your Hearing neatly explained “mechanical aids” to hearing, later referred to as hearing aids, and a “systematic hygiene for the conservation of hearing,” also known as cleaning your ears. Nearly 100 years later, hearing is still a vital health care concern, and Chris Berdik’s new book Clamor offers a deep dive into how sound can affect humans and other animals on the planet. The racket constantly echoing around Earth has real effects on animal health and behavior.

Life on Earth

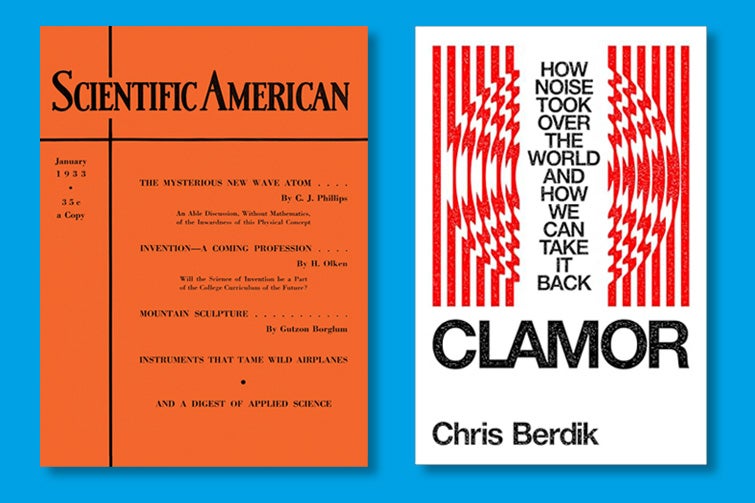

The Science of Life

by H. G. Wells, Julian Huxley and G. P. Wells

Doubleday, Doran & Company, 1931

When the Earth Was Green

by Riley Black

St. Martin’s Press, 2025

We were beside ourselves in April 1931 when we saw a copy of The Science of Life co-written by none other than celebrated author H. G. Wells himself, along with his son G. P. Wells and Julian Huxley (the “grandson of the great Huxley of Darwin’s day” and a “well-known professor of zoology,”) we enthused). We opened our review with “What a work!” and went on to rave about the book’s scope and length (nearly 1,500 pages), exclaiming that the 300 pages dedicated to evolution “cover every nook and cranny of the subject.” In their latest book, When the Earth Was Green, modern-day science writer Riley Black offers another beautiful and insightful exploration of the evolution of life on Earth. Black effortlessly brings readers billions of years into the past while maintaining the brevity, humor and gentle guidance that all science writing so desperately craves.

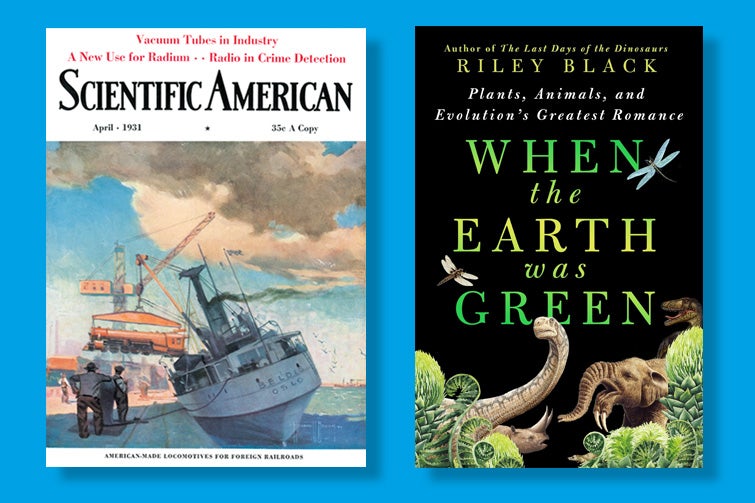

Antarctic Ecology, Vol. I and II

edited by M. W. Holdgate

Academic Press, 1970

Ends of the Earth: Journeys to the Polar Regions in Search of Life, the Cosmos, and our Future

by Neil Shubin

Dutton, 2025

In September 1970 Scientific American reviewed M. W. Holdgate’s impressive two-volume exploration of Antarctic ecology. The first part, we wrote, offered an “an appraisal of the geologic past … to the fishes and birds of the shore … to the soil and the vegetation and the land fauna.” And we noted that the second volume discussed conservation efforts to protect all this precious life. We thought “the most poignant graph in the book” was one showing “the terrible decline in the total mass of the baleen whales.” In the past 55 years, the Arctic environment has continued to change, documented by evolutionary biologist Neil Shubin’s latest book, Ends of the Earth. His sweeping overview of life and ice at the northernmost latitudes offers a crucial exploration of the Arctic of our time and the things that scientists are still learning from it.

Oxygen: A Play in 2 Acts

by Carl Djerassi and Roald Hoffmann

Wiley-VCH, 2001

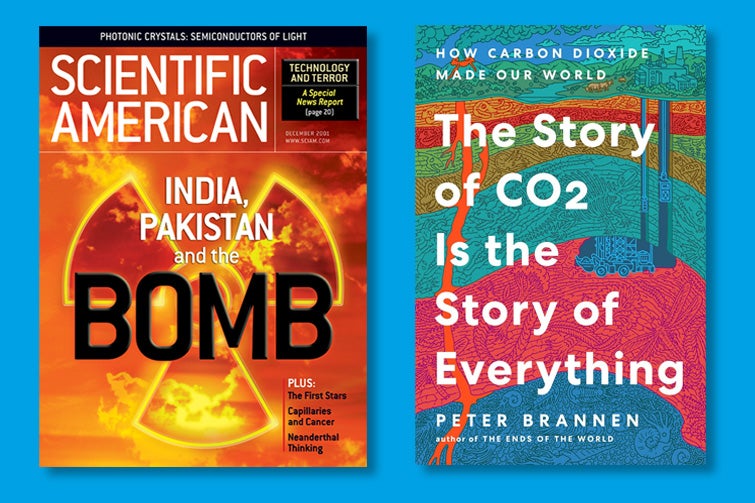

The Story of CO2 Is the Story of Everything: How Carbon Dioxide Made Our World

by Peter Brannen

Ecco, 2025

In July 2001 we expanded our books coverage to include plays, specifically off-beat plays written by scientists. With Oxygen, chemistry professors Carl Djerassi (“perhaps best known as the inventor of the birth-control pill,” we noted) and Roald Hoffmann applied their career experience to theater: In their play, the Nobel Prize Committee decides to retroactively honor the discovery of oxygen, and the drama begins as the committee members decide who to award the prize to. Molecular building blocks of our world are just as important in 2025. Peter Brannen’s latest book, CO2 Is the Story of Everything, makes a striking case that carbon dioxide is the most important—but perhaps misunderstood—chemical compound on Earth, in the galaxy and in us carbon-based life-forms.

Artificial Intelligence

Machines Who Think: A Personal Inquiry into the History and Prospects of Artificial Intelligence

by Pamela McCorduck

W. H. Freeman and Company, 1979

Empire of AI: Dreams and Nightmares in Sam Altman’s OpenAI

by Karen Hao

Penguin Press, 2025

In March 1980 Scientific American reviewed author Pamela McCorduck’s 1979 book Machines Who Think and found that it offered a real insight into the power players of machine learning, specifically “what they do, say and plan.” At the same time, we lamented the lack of figures and wished there were photographs of father of machine intelligence Alan Turing. Machine learning is even more relevant today, evidenced by this year’s breakout book: Empire of AI, by journalist Karen Hao. She offers readers a modern-day peak into artificial intelligence moguls of our time, including Sam Altman, Elon Musk and Peter Thiel. Both books wrestle with similar questions: while McCorduck asked whether a machine should think, Hao asks: What have these machines already been taught to think, and what will they think to do next?

Math

Number: The Language of Science

by Tobias Dantzig

Macmillan, 1930

The Language of Mathematics: The Stories behind the Symbols

by Raúl Rojas

Princeton University Press, 2025

In September 1930 Scientific American recommended Tobias Dantzig’s book Number, the Language of Science because “it [wasn’t] a mere schoolbook on algebra, geometry, calculus, or any other horrible kind of formal mathematical torture.” Instead it offered readers insight into surprisingly interesting mathematical topics such as the origin of zero and the history of the infinity symbol. We were so certain that our readers would enjoy this one that we predicted that any reader would “exclaim at least once per page, ‘Well, I never thought of that before.’” Mathematician Raul Rojas’s book about math symbols, published in January 2025 by Princeton University Press, offers the numeral nerds among us a guide to the fascinating history of mathematical symbols, some of which have become commonplace in everyday life.