On August 19 Hurricane Erin is crawling past the Bahamas as a strong Category 2 storm and is due to head toward the Carolinas and then veer northeast over the open Atlantic Ocean. Although the storm’s eye may never come within 300 miles of the mainland U.S., most of the East Coast—from Miami to Maine—is under a moderate or high risk of rip currents.

U.S. rip current risk map for August 18-19, 2025. Red indicates life-threatening rip currents are likely. Swimming conditions are unsafe for all levels of swimmers. Stay out of the water. Always follow advice from the local beach patrol and flag warning systems.

In the U.S. rip currents cause about 100 fatal drownings each year and are responsible for four out of five beach rescues, according to a 2019 study. Here’s the science behind how rip currents work, why hurricanes can cause them at such great distances from land and what beachgoers need to know about the threat.

On supporting science journalism

If you’re enjoying this article, consider supporting our award-winning journalism by subscribing. By purchasing a subscription you are helping to ensure the future of impactful stories about the discoveries and ideas shaping our world today.

Rip Currents Explained

Rip currents are a common phenomenon even without a hurricane roiling the distant ocean, says Melissa Moulton, a coastal physical oceanographer at the University of Washington. “Rip currents are strong seaward currents that are caused by breaking waves,” she says. “They can be as narrow as an alleyway or as wide as a multilane highway; they can last for just a few minutes or sometimes a number of hours.” At their fastest, they can beat an Olympic swimmer.

These currents are an inevitable by-product of ocean physics on a complex shoreline, says Chris Houser, a coastal geomorphologist at the University of Waterloo in Ontario. Waves “are constantly moving water toward that shoreline,” Houser says. That might sound obvious, but there’s a corollary people may not think about too carefully, he adds: all that water has “got to go somewhere.”

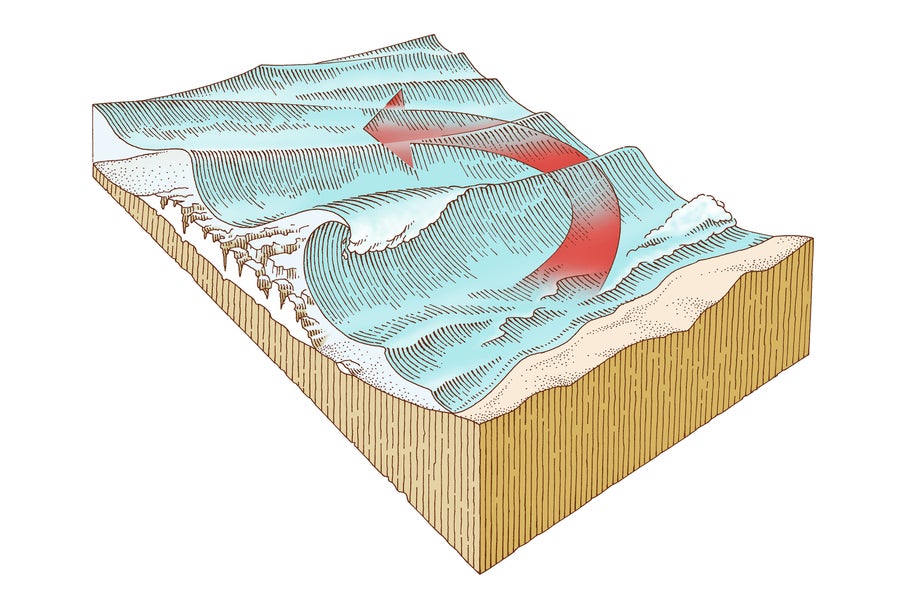

That “where” is back out to sea, and rip currents are one of the key routes by which water gets there. A rip current develops from variations in how waves break along a coastline, causing water from crashing waves to stay at the surface and flow sideways, then out to sea. (If the water instead travels down and straight back out, it forms an undertow, although the two terms are sometimes conflated.)

READ MORE: Why Storm Surge Is Dangerous—And Becoming More Frequent

Rip currents are more likely to develop when a coastline is more complex, in terms of either the visible shore—a feature such as a jetty or a rocky point can trigger rip currents—or the underwater topography of sandbars that raise the ocean floor. “Over a shallow sandbar, you’re getting larger breaking waves compared to, say, over a channel or a deeper spot,” says Greg Dusek, a coastal physical oceanographer at the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. That creates variation in breaking waves and funnels outgoing water toward deeper areas that can form rip currents.

Where the coastline is shallower, larger waves can form, pushing more water onto shore. This water can then be forced back out to sea where the underwater topography is deeper, forming a rip current (red arrow).

Gary Hincks/Science Source

The result is a misleading picture at the beach. “You’re looking along the shoreline, and you see areas of waves that are breaking and areas that are not breaking,” Houser says. “You might actually think that the calm water is safest. It’s probably a rip current.” (Although that doesn’t mean the breaking waves are safe either.)

Why Distant Hurricanes Trigger Rip Currents

The picture becomes even more confusing when a hurricane passes far from shore, as Hurricane Erin is doing this week. With the stormy winds hundreds of miles away, conditions onshore might be gorgeous—but a hurricane can still make its presence known.

Just as an earthquake can trigger a tsunami that crosses an entire ocean, even a distant hurricane can whip up beach surf. “You might be standing on the beach, and it’s a sunny day, no strong winds,” Moulton says. “Because waves transport energy over very long distances very efficiently, we’re not seeing the winds or anything from the hurricane, but we will see the wave energy.”

The sizes of waves produced by a hurricane are determined by the sustained windspeeds inside the storm, the amount of ocean that the storm covers and the speed at which it travels. In general, faster winds, a larger area and slower movement tend to lead to taller waves that travel farther. When those waves hit a shoreline, they’re more likely to trigger rip currents. “The bigger the waves, the stronger the rip—if you have the physical conditions present for rips to be there,” Houser says.

Hurricane Erin, swirling through the Atlantic Ocean on August 18, 2025.

And the risk of rip currents can linger long after a storm has passed, Dusek warns. That’s in part because the storm may have reshaped the visible or underwater topography of a beach. And when a distant storm is creating waves that are six or 10 feet tall, people typically know to stay out of the ocean. But when waves become a little less dramatic and local conditions are beautiful, it’s more difficult to see the dangers of rip currents.

Dusek expects that rip current risks along the East Coast could remain high through the rest of the week and perhaps into the weekend. That’s particularly dangerous toward the end of summer, when people flock to the beach. “In the wintertime, we have lots of winter storms up and down the East Coast, but rip currents aren’t typically a concern because no one’s swimming,” he says.

How to Stay Safe from Rip Currents

Moulton, Houser and Dusek all agree that staying safe from rip currents means following two guidelines: only swim at beaches where a lifeguard is present and obey any warnings from lifeguards or local officials about staying out of the water.

“If they have a red flag flying, it’s not because they’re being overly cautious,” Houser says. “They are seeing something that you can’t.”

If you do happen to get caught in a rip current, Houser says, advice on what to do has changed in recent years. Officials used to recommend people try to swim parallel to shore to “break the grip of the rip.” But in the heat of the moment, it’s difficult to know which way is which, he says. So officials have pivoted to “flip, float, follow.”

“Flip means don’t put your feet down; flip so that your head is up and you are floating on your back,” Houser says. “Then you start to follow the rip current. Allow it to take you slightly.” He’s done this and says that, even with a floatation device, it’s terrifying. But instead of wasting your strength against a fierce current, the strategy allows you to get your bearings and signal to a lifeguard while reducing the risk of drowning.