During her training in anthropology, Dorsa Amir, now at Duke University, became fascinated with the Müller-Lyer illusion. The illusion is simple: one long horizontal line is flanked by arrowheads on either side. Whether the arrowheads are pointing inward or outward dramatically changes the perceived length of the line—people tend to see it as longer when the arrowheads point in and as shorter when they point out.

The Müller-Lyer illusion.

Franz Carl Müller-Lyer, restyled by Eve Lu

Most intriguingly, psychologists in the 1960s had apparently discovered something remarkable about the illusion: only European and American urbanites fell for the trick. The illusion worked less well, or didn’t work at all, on groups surveyed across Africa and the Philippines.

On supporting science journalism

If you’re enjoying this article, consider supporting our award-winning journalism by subscribing. By purchasing a subscription you are helping to ensure the future of impactful stories about the discoveries and ideas shaping our world today.

The idea that this simple illusion supposedly only worked in some cultures but not others compelled Amir, who now studies how culture shapes the mind. “I always thought it was so cool, right, that this basic thing that you think is just so obvious is the type of thing that might vary across cultures,” Amir says.

But this foundational research—and the hypothesis that arose to explain it, called the “carpentered-world” hypothesis—is now widely disputed, including by Amir herself. This has left researchers like her questioning what we can truly know about how culture shapes how we see the world.

When researcher Marshall Segall and his colleagues conducted the cross-cultural experiment on the Müller-Lyer illusion in the 1960s, they came up with a hypothesis to explain the strange results: difference in building styles. The researchers theorized that the prevalence of carpentry features, such as rectangular spaces and right angles, trained the visual systems of people in more wealthy, industrialized cultures to perceive these angles in a way that make them more prone to the Müller-Lyer illusion.

The carpentered-world hypothesis took off. Psychologists tested other illusions involving straight lines and linear perspective across cultures and found similar results, suggesting that the culture or environment in which someone grows up could shape their brain’s visual system and literally affect how they see the world. This is also known as the “cultural by-product hypothesis.”

It turns out that the story wasn’t so simple. After connecting with Chaz Firestone, now a cognitive scientist at Johns Hopkins University, Amir learned that other studies of the Müller-Lyer illusion contradicted the anthropological explanations she had been given in grad school. The two researchers recently compiled a slew of evidence against this claim, publishing their argument in Psychological Review. For starters, the illusion still works when the lines are curved or even when there are no lines at all and dots take their place, suggesting the illusion’s effect isn’t reliant on hallmarks of carpentry. Even more convincing, kids who have been blind their whole life and undergo lens replacement surgery are susceptible to the illusion shortly after gaining sight. And even some animals, such as birds, fish, reptiles, insects and nonhuman mammals, seem to fall for the trick. It seems that our susceptibility to the Müller-Lyer illusion comes not from shared visual environments but from something more innate.

So what explains the results in the seminal carpentered-world studies? It’s possible—or rather quite likely—that these were the results of “research practices now recognized to be problematic by modern methodological standards (including discarding inconvenient data points, and failing to conduct appropriate statistical tests),” Amir and Firestone wrote. Even then, the results were highly inconsistent across studies, the researchers found.

Many psychologists now think it’s unlikely that culture or environment could affect brain processes as ancient and foundational as the basic features of vision, such as the detection of depth, contrast and lines. But culture might affect how we see the world at a higher level. Some results suggest that more complex cognitive capacities such as memory and attention are guided by our upbringing, which can impact what we report seeing in the world around us, Amir says.

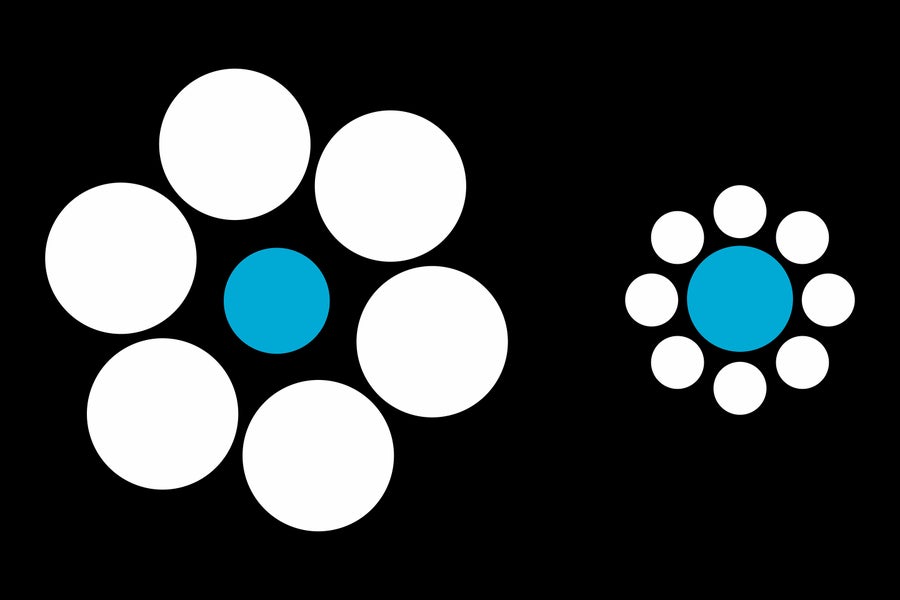

In a recent study, Michael Frank, a developmental psychologist at Stanford University, and his team studied perceptual and cognitive differences between people in the U.S. and China. The results, published last year in the Journal of Experimental Psychology: General, were a mixed bag. The researchers found no strong cultural differences in the Ebbinghaus illusion, in which the perceived size of a circle is affected by the size of circles around it.

Neslihan Gorucu/Getty Images

But they did find cultural differences in visual tasks that relied more on attention and interpretation. When Chinese participants were asked to describe an image they had just seen, they tended to describe the background more than the objects in the foreground, whereas U.S. participants did the opposite. For example, given an image of a red bike set against the background of a vibrant lawn, Chinese participants would focus on providing detail about the green grass, whereas U.S. participants would describe the red bike.

“The tasks that yielded differences in our study tended to tap into linguistic descriptions and slow, effortful reasoning processes,” Frank explains.

It’s challenging for researchers to pinpoint what aspects of culture are driving these higher-level differences. Some cross-cultural psychologists point to Eastern collectivism and Western individualism to explain such results, but Frank remains agnostic. So does Sumita Chatterjee, a research consultant, who earned a Ph.D. studying the influence of culture on visual perception at the University of Glasgow.

Linking the behaviors of specific cultural groups to larger concepts always comes “with the risk of overgeneralization,” Chatterjee says. “Stringently ascribing a list of behaviors to specific categories like ‘East’ and ‘West’ can blind us to the true reasons behind the differences in behavior.”

Similarly, Amir says that when tying a perceptual difference to a specific aspect of culture, such as carpentry or collectivism, researchers should think hard about what they are truly measuring and avoid making too many assumptions, especially those that involve cultures outside their own.

For example, in one recent preprint paper that has not yet been peer-reviewed by other researchers, a team found differences in both visual attention and perception between members of the Himba tribe in rural Namibia and participants from urban parts of the U.K. and the U.S. When viewing a complex black-and-white image called the Coffer illusion, Himba participants focused on circular parts of the image while urban participants picked out the rectangular parts first. More research would be needed, however, to ascribe this difference causally to disparities between the shapes of each group’s buildings.

“I do think the general call to arms to study cognition across cultures is really important,” Amir says. “Some things might vary, and some things might not, but careful studies can potentially reveal both.”

Some initiatives are attempting to do just that. Frank and his colleagues began the Learning Variability Network Exchange (LEVANTE) project to improve cross-cultural comparison of learning and cognition across development. He also participates in large team science initiatives, such as ManyBabies, that bring together research groups from around the world to share methods and data. “Critically, in all of these efforts, there is ‘local’ representation, meaning that the research team includes individuals from the groups being studied,” Frank says. “These issues are super tricky, but I’m excited that we are moving forward as a field.”