September 10, 2025

3 min read

At the Peak of Hurricane Season, the Atlantic Is Quiet. Here’s Why

Hurricane activity in the Atlantic basin is historically at its peak on September 10—but not this year

In May, as Atlantic hurricane season loomed, meteorologists worried that above-average tropical activity, combined with cuts to the federal government’s weather agency, could result in disaster. But so far, the season’s effects have been mild. And although September 10 has historically marked the peak of Atlantic hurricane activity, the basin has gone nearly two weeks with nary a tropical storm in sight—and none expected during the coming week either.

Still, experts caution that the current lull in tropical activity doesn’t mean that this year’s threat of hurricanes has passed or that forecasters’ predictions about this season were wrong. Here’s what you should know about hurricane activity right now and this year in general.

The most recent tropical storm, Fernand, dissipated on August 28, nearly two weeks ago. Earlier this month, meteorologists were closely monitoring a system that they thought had the potential to turn into a serious storm, but it hit a patch of dry air and fell apart—not a particularly unusual scenario for a would-be storm at such an early stage.

On supporting science journalism

If you’re enjoying this article, consider supporting our award-winning journalism by subscribing. By purchasing a subscription you are helping to ensure the future of impactful stories about the discoveries and ideas shaping our world today.

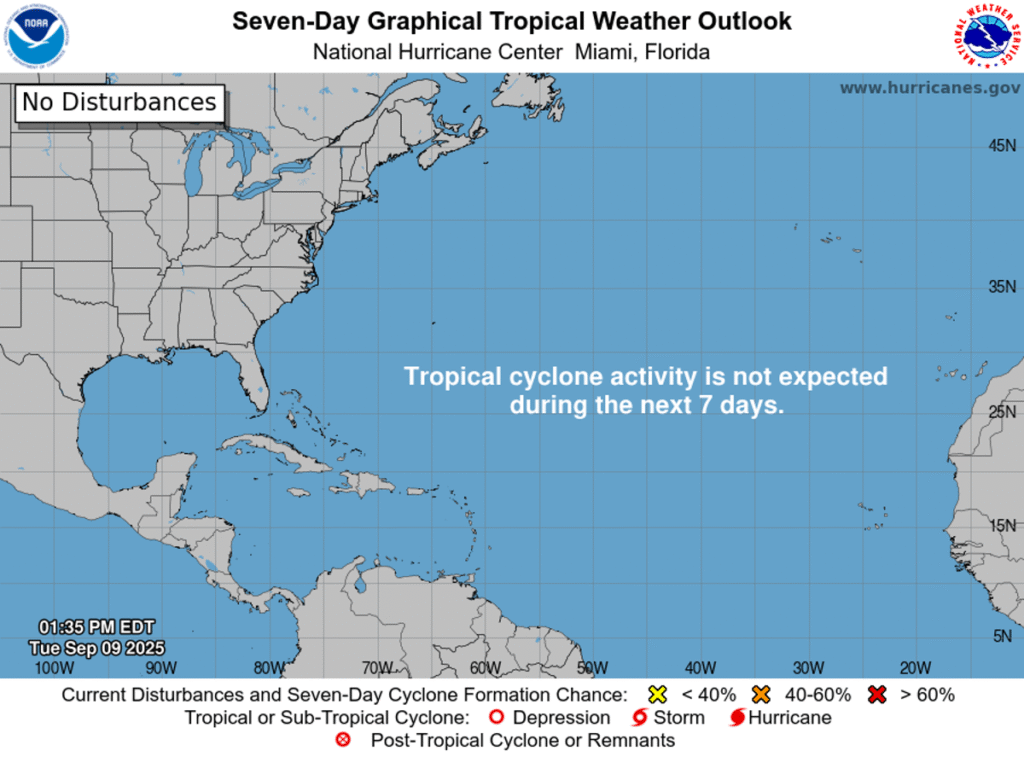

And today the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration’s National Hurricane Center displays that most optimistic of Atlantic basin forecasts: an empty map labeled “no disturbances”—an indication that meteorologists don’t expect any tropical activity of note within the next seven days.

READ MORE: Hurricane Science Has a Lot of Jargon—Here’s What It All Means

Such a stretch of tropical quiet isn’t particularly strange, says Matthew Rosencrans, a meteorologist and lead hurricane season forecaster at the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration’s National Centers for Environmental Prediction, but it’s rarer to see such a lull right over the traditional peak of hurricane season. Rosencrans says that the last September 10 with no tropical storm activity at all was in 2016.

Rosencrans and Brian McNoldy, a hurricane researcher at the University of Miami, agree that the lull is primarily linked to a global atmospheric phenomenon called the Madden-Julian Oscillation (MJO), which moves high-pressure air masses eastward around the planet every month or two. High-pressure air tends to be drier—hardly conducive to moisture-fueled hurricanes—and to sink, making it harder for a storm system to develop convection, the upward movement of warmth that feeds tropical storms.

The state of the MJO last month was such that low-pressure air, which can foster tropical activity, was positioned over the Atlantic Ocean. And sure enough, Hurricane Erin formed and then exploded into a Category 5 storm, albeit one that predominantly stayed over the ocean. By late August, the cycle had brought high-pressure air over the Atlantic, leading to the current lull.

Meteorologists forecast that within the next 10 to 14 days, the global cycle will bring low-pressure conditions back over the Atlantic Ocean, making the atmosphere more prone to tropical activity again.

And besides atmospheric pressure, many of the key factors for hurricane formation are present. Any tropical storm must begin as a seed storm, and seeds storms are still forming at their usual rate. Further, hurricanes feed off hot ocean water, which has been plentiful this year. “The ocean conditions are absolutely ready for anything,” McNoldy says. Wind shear—in which winds at different heights point in different directions, a phenomenon that can tear apart a brewing storm—has been a little high but not enough to prevent serious tropical activity if other factors align.

READ MORE: 20 Years after Katrina, Major Hurricane Forecasting Advances Could Erode

That means it’s far too early to write off this hurricane season, Rosencrans and McNoldy agree.

In May meteorologists at the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration announced their outlook for this season: a total of 13 to 19 tropical storms and hurricanes combined, including between six and 10 hurricanes and three to five major hurricanes of Category 3 or higher. So far a total of six tropical storms have formed. Of those six, only Erin became a hurricane, although it did reach a peak intensity of Category 5.

That means the season overall—which officially runs from June 1 to November 30—is unfolding to be about as strong as predicted—and has plenty potential risk remaining.

Even just last year offers a cautionary tale, Rosencrans says: after a similar lull in late August and early September, tropical activity spiked to the highest on record for late September and onward, including the deadly hurricanes Helene and Milton.

“It’s still hurricane season,” McNoldy says. “We have half the season left, so I have no doubt at all we’ll be watching storms sooner than we want to be.”

It’s Time to Stand Up for Science

If you enjoyed this article, I’d like to ask for your support. Scientific American has served as an advocate for science and industry for 180 years, and right now may be the most critical moment in that two-century history.

I’ve been a Scientific American subscriber since I was 12 years old, and it helped shape the way I look at the world. SciAm always educates and delights me, and inspires a sense of awe for our vast, beautiful universe. I hope it does that for you, too.

If you subscribe to Scientific American, you help ensure that our coverage is centered on meaningful research and discovery; that we have the resources to report on the decisions that threaten labs across the U.S.; and that we support both budding and working scientists at a time when the value of science itself too often goes unrecognized.

In return, you get essential news, captivating podcasts, brilliant infographics, can’t-miss newsletters, must-watch videos, challenging games, and the science world’s best writing and reporting. You can even gift someone a subscription.

There has never been a more important time for us to stand up and show why science matters. I hope you’ll support us in that mission.