You have full access to this article via your institution.

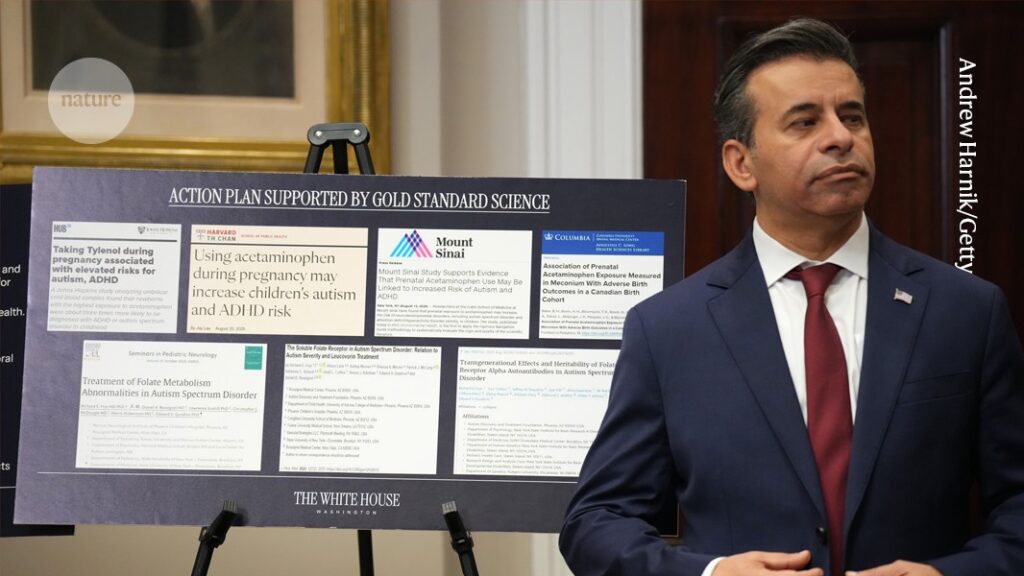

Head of the US Food and Drugs Administration Marty Makary at the White House on 22 September.Credit: Andrew Harnik/Getty

On 22 September, the United States’ top public-health officials stood alongside President Donald Trump at the White House and delivered a message that went around the world in an instant. The US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) said it intends to change its guidance on acetaminophen — also known as paracetamol — a household painkiller marketed in the United States as Tylenol. The FDA published a statement saying that the agency is initiating a change to its labelling “to reflect evidence suggesting that the use of acetaminophen by pregnant women may be associated with an increased risk of neurological conditions such as autism and [attention deficit hyperactivity disorder] in children”. What is disconcerting is that this proposed action from the US drug regulator does not accurately represent the spectrum of research findings, nor the consensus among researchers. That consensus must be expressed with nuance, because of the uncertainty that always exists in scientific research. By making definitive statements such as “Don’t take Tylenol” and “Fight like hell not to take it”, Trump risks weaponizing that uncertainty to the detriment of public health.

Trump links autism and Tylenol: is there any truth to it?

In pregnancy, paracetamol is typically recommended for pain and for fevers, at the lowest possible dose and for the shortest period of time, under the guidance of a qualified medical professional. It is recommended because it relieves pain with minimal risks, and because untreated fevers can cause harm to unborn babies. Medicines regulators overwhelmingly agree that there is no consistent body of evidence to suggest that this guidance should change. And last week, they were quick to say so.

National regulators and public-health bodies are not rushing to change their guidelines. On the contrary, the World Health Organization issued a statement saying that “there is currently no conclusive scientific evidence confirming a possible link between autism and use of acetaminophen during pregnancy”. The European Medicines Agency said its guidance is also unchanged — that there is: “no evidence that taking paracetamol during pregnancy causes autism in children”. It was the same message from national regulators across the world, from Australia to the United Kingdom, and from state-level bodies in the United States, too, along with professional societies that represent researchers and clinicians in autism spectrum disorder, obstetrics and gynaecology.

It’s a welcome development that public-health organizations have quickly countered these inaccurate claims. Correcting misinformation matters now more than ever because of the speed at which it spreads. What the United States says and does matters to people both inside and beyond its borders, because of its considerable influence on health and science policies. It is therefore crucial for trusted organizations with expertise and for those in positions of responsibility in global public health to quickly correct the record, and have their messages amplified.

Cherry picking

Although a small number of studies report an association between paracetamol and autism, public-health bodies around the world agree that these findings are not conclusive, and are outweighed by other, more robust findings that have found no corresponding link. The FDA’s statement does acknowledge that “a causal relationship has not been established and there are contrary studies in the scientific literature”. However, a White House statement published on the same day does not mention this.

What happens if pregnant women stop taking Tylenol?

One of the largest studies1, involving data from nearly 2.5 million children born in Sweden, did not find conclusive evidence of an association. Public-health research Viktor Ahlqvist at the Karolinska Institute in Stockholm and his colleagues examined health records for children born between 1995 and 2019. The researchers examined data on paracetamol use during pregnancies and subsequent autism diagnoses among the children. They also analysed sibling pairs in which one had been exposed to paracetamol and the other hadn’t, to control for confounding factors. There was no evidence of an association in the sibling study.

A birth-cohort study2 in Japan (also including siblings) also found no conclusive link. Yusuke Okubo, a public-health researcher at the National Center for Child Health and Development in Tokyo, and his colleagues examined records from around 200,000 children.

The White House statement cites a study3 by epidemiologist Diddier Prada at the Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai in New York City and his colleagues. However, it neglects to mention that the study says an association between acetaminophen and autism “warrants caution”. The study authors also “recommend judicious acetaminophen use — lowest effective dose, shortest duration — under medical guidance”.

Trump team backs an unproven drug for autism — but does it work?

As we have written in these pages before, the regulation of medicines always requires a careful risk–benefit calculation. Drugs are never risk-free. When medicines and other therapeutics are approved by regulators, it is because researchers and other specialists working for regulatory agencies have taken the time to evaluate all of the available evidence on safety and efficacy and have judged that the benefits outweigh the risks.

In public health, as in science more broadly, decisions are made by regularly assessing all of the available evidence, taking into account the quality of studies, and not just by citing those statements that support one view over others. If new evidence emerges, recommendations are reconsidered and, if necessary, revised. That is how the world’s public-health bodies operate because they agree there is, for now, no better way to improve health care and reduce risks. The fact that the US federal agencies are now moving away from this approach poses real dangers to the health of people living there and around the world.

Public-health bodies everywhere must continue to correct the record, and do so quickly when required. The risks of inaction are too great. In science, there is almost always uncertainty. The responsible thing to do is communicate studies in a way that represents the fullness of their findings; and in public health to ensure that decisions are made in line with the consensus of experts.