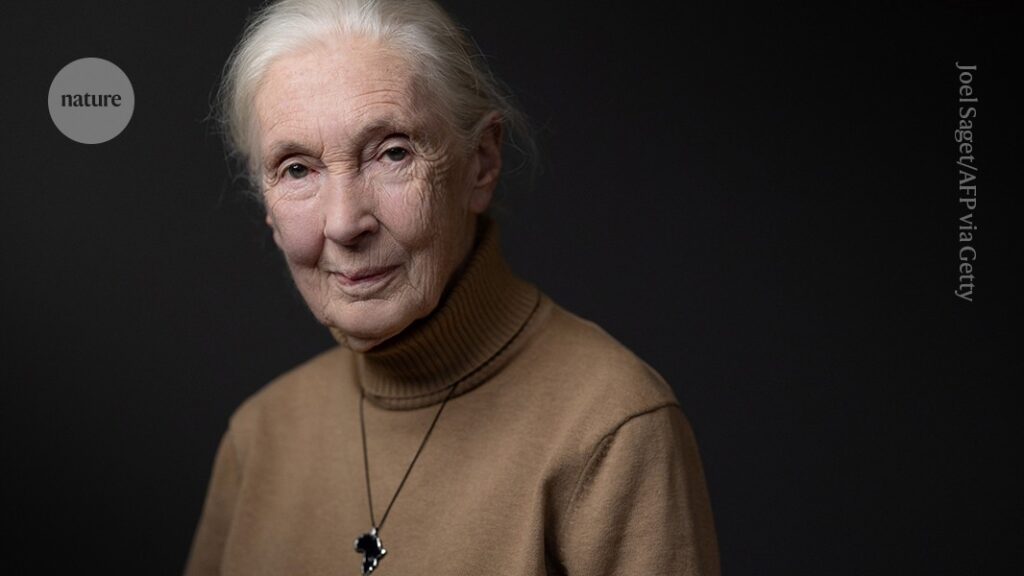

In the 1960s, scientists classed chimpanzees, bonobos, gorillas and orangutans as a distinct family (Pongidae), thinking that these great apes had long diverged from humans. Few scholars expected that, in nature, these apes would display strikingly human-like behaviour. Jane Goodall, who has died aged 91, overturned this view with her groundbreaking observations of wild chimpanzees (Pan troglodytes).

Jane Goodall’s legacy: three ways she changed science

Her discoveries foreshadowed the genetic evidence showing that chimpanzees, bonobos (Pan paniscus) and humans are more closely related to one another than to gorillas (Gorilla spp.) and orangutans (Pongo spp.). The findings had a major role in shifting perceptions towards recognizing the importance of emotions, personalities and complex cognition, reshaping scientific and public understanding of human evolution. She was a tireless advocate for conservation, the welfare of captive chimpanzees and the protection of habitats — work now carried forwards through the Jane Goodall Institute in Washington, DC.

Her fascination with animals began early. Born in north London in 1934, she famously disappeared during a Second World War air raid when she was around six years old, only to be found sitting quietly in a chicken coop, watching a hen lay an egg. She often told this story to illustrate the patience and curiosity that defined her life’s work.

In 1957, after working as a secretary for some years, Goodall accepted a friend’s invitation to visit Kenya. In Nairobi, she sought out the renowned palaeontologist Louis Leakey, who invited her to join him and his wife Mary on a fossil-hunting expedition in Olduvai Gorge in northern Tanzania, known as the Cradle of Humankind for its rich deposit of early hominid fossils and stone tools. During the trip, she committed to studying chimpanzees in what is now called Gombe National Park in Tanzania — a small, 35-square-kilometre patch of forest that Leakey had long hoped to investigate.

Biggest ever study of primate genomes has surprises for humanity

To prepare, she persuaded John Napier, a leading anthropologist, to tutor her privately in primatology. She was dismayed to learn that the main chimpanzee study of the time, conducted in 1929–30, had lasted for only four months and had been done by a large, intrusive expedition operating in classic colonial excess. She was not surprised that it had produced few results.

By contrast, when she arrived in Gombe in July 1960, she spent many months patiently tracking chimpanzees in the hills, sometimes sleeping alone in the park. By her fourth month, she had made her first world-shaking discoveries: chimpanzees not only ate and shared meat but also fashioned tools. The tools were modified grass stems that were then used to extract edible termites from their mounds (J. Goodall Nature 201, 1264–1266; 1964).

Her findings earned her long-term support. In 1961, she began a PhD at the University of Cambridge, UK, under zoologist Robert Hinde, who encouraged her to focus on social relationships, individual personalities and the expression of emotions. She gained intimate access to chimpanzees by providing them with bananas, which allowed her to document their lives in unprecedented detail. She observed their political manoeuvring, deception, coalitional aggression and cooperation outside family groups — behaviours that indicated previously unsuspected levels of social intelligence.