October 6, 2025

4 min read

See Stunning Feline Photography Revealing the Science of Cats

Tim Flach captures his fascination with the science of cats in stunning photographs from his new book Feline

Cats with pale blue eyes carry a mutation that prevents color pigments from forming and spreading through the body before birth. In eyes without pigments, light can only bounce off tiny stray particles in the iris that reflect only blue light’s very short wavelengths.

Photographer Tim Flach’s new book is unusually personal: it includes images not only of his cat—a regal orange-and-white former barn kitten named Loki—but also of his brain, thanks to MRI scans gathered as he looked at cute images.

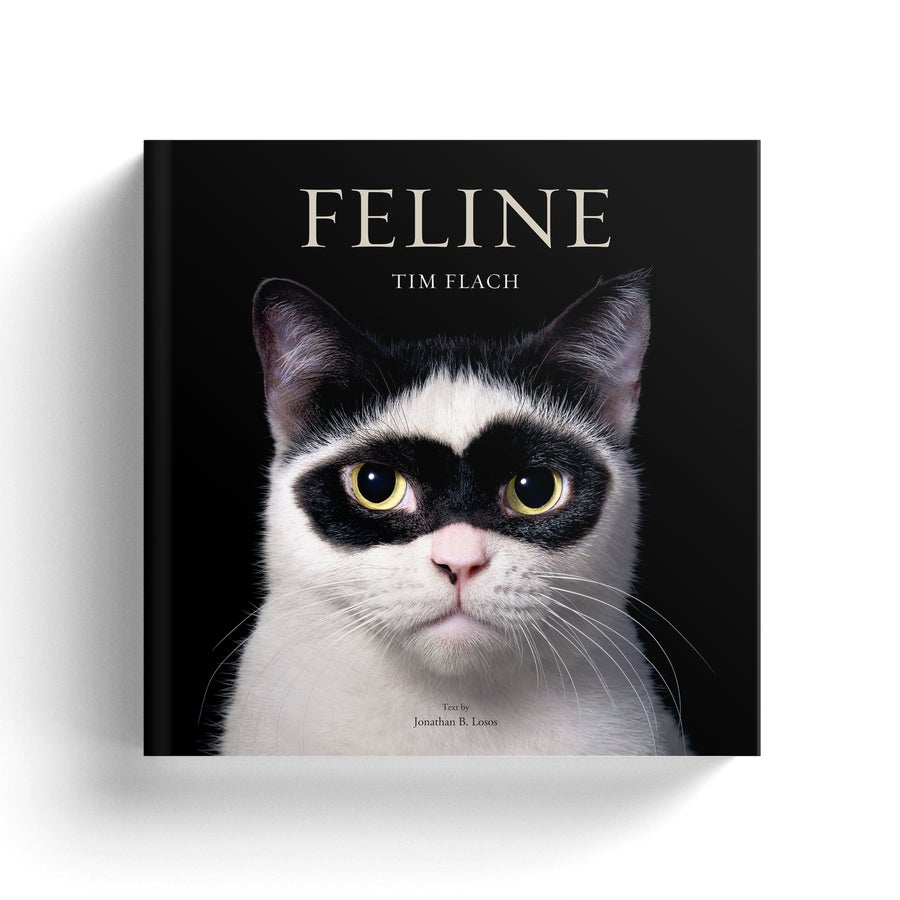

The photographer has dedicated previous books to horses, dogs and endangered species—and shot photos of songbirds for Scientific American—but had been hesitant to take on the notoriously uncooperative felines. “My publishers from day one have been wanting me to do a cat book,” Flach says. “My problem was, how can I do a cat book and come out with dignity?” But he persevered, producing a book called Feline (Abrams) that combines his images with text by Jonathan Losos, an evolutionary biologist at Washington University in St. Louis.

As the book came together, Flach was fascinated to learn what science knows—and doesn’t know—about felines of all forms and the long evolutionary history of cats. “Thirty million years back, we’d have recognized a cat,” he says, “whereas we wouldn’t recognize [human ancestors] somewhere, arboreally going up some tree.”

On supporting science journalism

If you’re enjoying this article, consider supporting our award-winning journalism by subscribing. By purchasing a subscription you are helping to ensure the future of impactful stories about the discoveries and ideas shaping our world today.

READ MORE: Cats Are Perfect. An Evolutionary Biologist Explains Why

The book also nods to conversations about photo manipulation and generation, including by artificial intelligence, as Flach and the rest of us attempt to navigate a world of doctored images.

“The problem in the past used to be just getting the cat to stay on the table,” he says. “Now the problem is proving it was ever there in the first place.”

This Persian cat named Atchoum became an Internet star because of his hypertrichosis, a condition that causes excess hair growth and claw thickening. The condition more often occurs in humans—it can be either genetic or a side effect of certain medications.

This image shows off the talents of athletic Savannah, a cross of the domestic cat with a small African cat called a serval, nicknamed the “giraffe cat.”

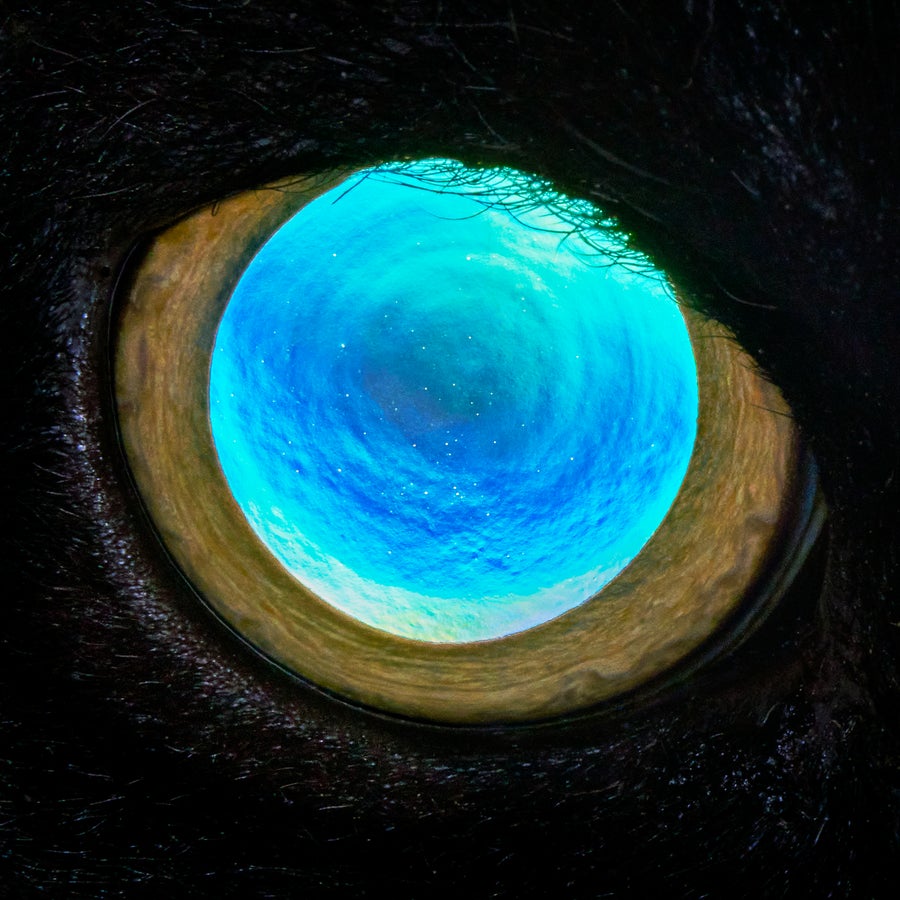

Flach worked with a Devon Rex cat named Gobbilino—and a rare camera lens he says he had to fly in just for the shoot—to capture this unique image highlighting the tapetum lucidum, a sheet of reflective cells behind the retina of the cat’s eye. These specialized cells contain crystals that reflect the light that reaches them back into the retina, increasing the amount of light the eyes can absorb. The tapetum lucidum also produces the eerie “eyeshine” that makes a cat’s eyes appear to glow in the dark—this is the light reflected off the crystals that is not absorbed by the retina. The image also shows how dramatically a cat can dilate its pupil, with the thin golden ring of the iris circling its vast extent.

Feline includes images of both beloved house cats and their wild compatriots, such as the Pallas’s cat (Otocolobus manul) pictured here. These cats range across Central Asia (they are called “manul” in the Kyrgyz language) and are specialized for life in in cold habitats, including at elevations as high as 16,000 feet. The Pallas’s cat is about the same size as a domestic cat but has particularly densely packed hairs that are the longest of any feline species, which make it appear larger. Another adaptation to their climate is the small size of their ears, which reduces heat loss.

Flach also traveled to South America’s massive Pantanal wetlands to photograph perhaps the region’s most regal resident: the jaguar (Panthera onca). The animals turned out to be surprisingly cooperative, Flach says. Traditionally nocturnal, these cats have lately become visible in the Pantanal during the day because they have learned the value of hunting local sunbathing reptiles called caimans, he says. “I got more shots in a day than I did of the domestic cats,” Flach says of the jaguars he photographed.

A litter of six 10-week-old Devon Rex kittens. The breed, which some say inspired the cinematic alien E.T., is known for expressive tail wags as well as furry legs and ears. The kittens are born with a plush “kitten coat” that they lose by around 11 weeks old, leaving them temporarily bald until their adult fur grows in.

Flach enlisted his assistant April Ironside’s cat Poppy, who enjoys drinking from the faucet, to show off the feline tongue. Cat tongues are characterized by tiny spines called papillae, which are made of the same compound as human fingernails, keratin.

Flach has extensively photographed wild species, especially for his previous book Endangered. One of his core aims is connecting viewers with the natural world. “It’s not about a distant nonhuman world,” he says. “It’s about making it personal, characterful and relatable.”

All cats are cute, but some are particularly cute—such as this Scottish fold named George, whose tiny ears and rounded face are exaggerated features that humans find appealing. (George appears in the same section of the book as the scans of Flach’s brain as he viewed baby photos.)

Gracing the cover of Feline is a cat named Boy, who lives in Indonesia and has found Internet fame because of his facial markings, which give him the appearance of a masked hero. “We’re unmasking what it is to be feline [in this book], and he seemed the perfect model,” Flach said in a video on his website in which he shared the experience of photographing the feline celebrity. “Boy was pretty professional,” he said. “I feel very, very lucky to have such a cool cat on the cover of my book.”

It’s Time to Stand Up for Science

If you enjoyed this article, I’d like to ask for your support. Scientific American has served as an advocate for science and industry for 180 years, and right now may be the most critical moment in that two-century history.

I’ve been a Scientific American subscriber since I was 12 years old, and it helped shape the way I look at the world. SciAm always educates and delights me, and inspires a sense of awe for our vast, beautiful universe. I hope it does that for you, too.

If you subscribe to Scientific American, you help ensure that our coverage is centered on meaningful research and discovery; that we have the resources to report on the decisions that threaten labs across the U.S.; and that we support both budding and working scientists at a time when the value of science itself too often goes unrecognized.

In return, you get essential news, captivating podcasts, brilliant infographics, can’t-miss newsletters, must-watch videos, challenging games, and the science world’s best writing and reporting. You can even gift someone a subscription.

There has never been a more important time for us to stand up and show why science matters. I hope you’ll support us in that mission.