After more than a decade of planning, the launch of the African Medicines Agency (AMA) is being celebrated in Mombasa, Kenya, this week at the Seventh Biennial Scientific Conference on Medical Products Regulation in Africa. The agency’s establishment marks a pivotal moment in Africa’s public health, at a time when the need for biomedical research conducted in Africa, focused on African health problems, has never been greater.

Africa holds higher levels of human genetic diversity than anywhere else on Earth, but this diversity has not been adequately studied. And many globally approved treatments and vaccines for diseases such as HIV/AIDS, malaria and tuberculosis are less effective, and can even be harmful in some people of African ancestry1,2.

Africa: tackle HIV and COVID-19 together

This year, cuts of billions of US dollars in international funding for biomedical research and health services in Africa have left millions of people without access to life-saving treatments or, in the case of researchers and health-care workers, unemployed. This demonstrates the immense vulnerability that comes with relying on funding from external donors.

What’s more, Africa’s phenomenal population growth and pace of urbanization is bringing fresh challenges — as well as opportunities — around health and disease. In Africa’s cities today, the inhabitants of increasingly affluent neighbourhoods are demanding high-quality medicines and health care. But in low-income areas, high population density, inadequate housing and poor sanitation are facilitating the spread of respiratory and diarrhoeal infections3. And everywhere, inadequate diets, air pollution, smoking and physical inactivity are driving increased rates of cardiovascular disease, diabetes and cancer4. By 2100, Africa is expected to host 13 of the world’s 20 largest cities5, and such inequalities are likely to worsen.

In the context of all these challenges, the AMA is more than just another regulatory body. It represents a test of whether Africa can claim its rightful place in shaping the science that will help to determine the health of its growing population.

If the AMA ensures that preclinical models for drug testing reflect African biology, that African genomes are woven into drug discovery from the start, and that clinical trials conducted on the continent are rigorous, it will improve the health of billions of people of African ancestry. By helping to generate a more complete picture of human genetic diversity and the links between genetic variation, disease and treatments, it will also redefine standards around drug development and clinical trials globally.

Drug discovery for Africa

Multiple studies spanning three decades have shown that individuals from different regions and ethnic backgrounds respond to medicines differently6. But although Africa holds around 18% of the world’s population and accounts for 25% of the global disease burden7, the continent’s genetic diversity is rarely considered in preclinical or clinical research8.

African biomedical data sets are hugely under-represented. Only 4% of the data in the Pharmacogenomics Knowledgebase (PharmGKB), a public database that provides information on the links between genes, drugs and diseases, come from individuals of African ancestry, for instance.

Likewise, to test drugs, researchers globally are increasingly relying on in vitro models developed from human cells or tissues. These include 3D cell cultures called organoids that mimic the structure and function of specific organs or tissues, and liver microsomes, which are collections of subcellular fragments derived from liver cells. But most of these tools have been derived from samples obtained from individuals of European ancestry9.

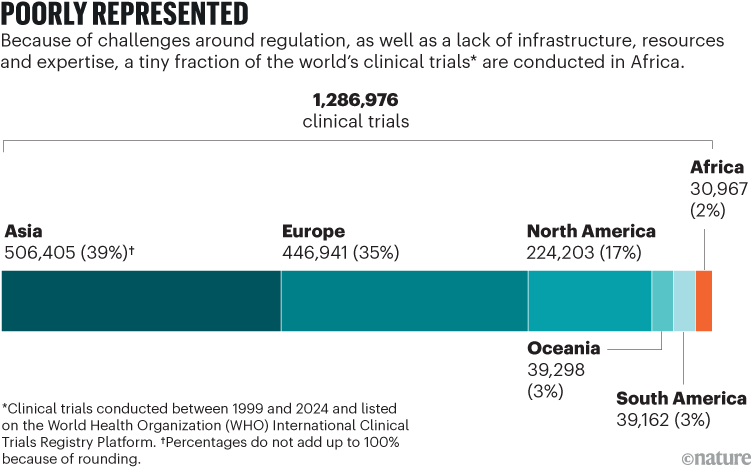

And when it comes to clinical trials, under 3% of them are conducted in Africa (see ‘Poorly represented’). A study published last year found that, between 2015 and 2023, out of tens of thousands of phase I trials (which assess the safety, side effects and optimal dosing regimen of treatments) conducted around the world, only 17 were conducted in Kenya, only 12 in Nigeria and only 3 in Ethiopia10, despite these countries being among the leaders in clinical research in sub-Saharan Africa.

Source: WHO International Clinical Trials Registry Platform

The result of all of this is the development of treatments that are ineffective or even detrimental for certain African populations. A compound called efavirenz, for example, was the key ingredient of first-line antiretroviral treatment in Africa and around the world until 201811. But Zimbabwean people with HIV who harbour certain genetic polymorphisms in CYP2B6, the enzyme responsible for metabolizing efavirenz, experience numbness in their feet and other symptoms of neurotoxicity when taking the drug12.

What’s more, diseases that disproportionately affect African populations, such as sickle-cell disease — which affects roughly 1 in 100 people living in West Africa, compared with 1 in 15,000 people living in Western Europe13 — have tended to be neglected.

Both sickle-cell disease and Parkinson’s disease contribute to about the same number of deaths globally each year, but whereas nearly 50,000 studies on Parkinson’s disease have been published in the past five years (according to a PubMed search), only around 7,800 studies on sickle-cell disease were published in the same period. (Deaths from Parkinson’s disease occur mainly in Asia, Europe and North America.)

Could Africa be the future for genomics research?

To ensure that African genomic diversity — and African needs — are better embedded into all stages of drug discovery and development, the AMA must ensure that African pharmacogenomic data (genetic information that signals how individuals will respond to medications) are integrated into drug discovery. It must mandate or incentivize the use of in vitro models derived from cells or tissues obtained from individuals of African ancestry9,14. And it must incentivize drug developers to focus on interventions for diseases that disproportionately affect African populations.

To do this, the AMA should require that applicants for regulatory approval demonstrate how they have considered genetic variability relevant to African populations in preclinical and clinical trials. Variants in the cytochrome P450 (CYP) gene family can affect the metabolism of drugs and toxins, for instance; variants in transporter proteins can influence how drugs are absorbed by, distributed in and eliminated from the body; and some variants of some genes, such as APOL1, increase people’s risk of developing a disease. (The APOL1 variants G1 and G2 are more common in individuals of African ancestry and a major risk factor for chronic kidney disease.)

The AMA should require that investigators use models derived from cells or tissues from individuals of African ancestry in all toxicity, efficacy, drug-metabolism and pharmacokinetic studies (which examine what the body does to drugs over time) submitted to it for approval. Or, to incentivize those applying for regulatory approval to take their treatment to the next phase of testing, the agency should offer expedited review pathways or reduced application fees when preclinical studies use ‘Africa-relevant’ tools.

An educator gives a talk on reproductive health in Harare, Zimbabwe.Credit: Jekesai Njikizana/AFP via Getty

In collaboration with African research institutions and global consortia, such as the Innovative Medicines Initiative, a public–private partnership involving the European Union and European life-science industries, the AMA should promote the creation of continent-wide pharmacogenomic databases.

Through partnering with African academic institutions, such as the Holistic Drug Discovery and Development Centre at the University of Cape Town in South Africa, and global funders, such as the Gates Foundation, the agency can help to drive the development of biobanks across Africa — facilities that collect, store and manage human biological samples. This would give more researchers across the continent access to Africa-relevant preclinical tools.

Ultimately, pharmaceutical companies, both in Africa and worldwide, could use these data and resources, in conjunction with artificial intelligence and other computational tools, to make predictions about how certain compounds will affect a given population. In fact, to encourage multinational drug developers to use such data sets and biorepositories, the AMA could help to ensure that open-access African data sets are interoperable with other platforms used in drug development, such as PharmGKB.

Harmonizing regulation

Alongside these steps to make biomedical research and drug discovery more relevant to African populations, the AMA needs to make it much easier for drug developers to conduct clinical trials on the continent.

Currently, drug developers wanting to work in Africa are hampered by insufficient or inadequate laboratories and infrastructure, a shortage of trained scientists who can run clinical trials, a lack of experts in research ethics and regulation, and variability in countries’ laws and standards around the handling of biological samples.

The AMA can help to increase the number of phase I trials being conducted in Africa by fostering partnerships between Africa-based research institutions, such as the Kenya Medical Research Institute in Nairobi, and international funders. It could also work with some of Africa’s continent-wide organizations, such as the International Vaccine Institute’s Africa Regional Office, which was established last year in Kigali, Rwanda, to boost research and development (R&D) of vaccines on the continent.

To ensure that efforts in different countries are coordinated, the agency must help to develop a central database for clinical trials conducted in Africa, perhaps building on the work of the Clinical Trials Community Africa Network. This group of African research-ethics bodies, research institutions and pharmaceutical companies is coordinating a network of clinical trial sites and laboratories to harmonize clinical trials conducted in Africa.

Africa’s rapid population growth is posing fresh health challenges.Credit: Olasunkanmi Ariyo/Getty

As a central, umbrella organization, the AMA should coordinate the reviews of applications for clinical trials and thereby facilitate the design of large-scale, multicountry phase II studies, which assess the efficacy and safety of treatments. Such studies, when conducted independently in any one country, often lack the sample sizes needed to reveal clinically meaningful differences in how genetic subpopulations differ in their response to a treatment.

By harmonizing the regulatory environment across the continent, the AMA can help to facilitate phase III clinical trials (which aim to provide evidence of therapeutic efficacy and safety in thousands of patients in multiple countries), phase IV studies (evaluations of treatments in real-world settings), and the monitoring of fake medicines, too.

Five traps to avoid

To promote a healthy ecosystem for biomedical research and drug and vaccine development in Africa, the AMA must beware some of the pitfalls that have hampered efforts of other continent-wide health initiatives, including the European Medicines Agency (EMA) in its early years.

First, the AMA must not let Africa’s diverse countries pull in different directions and erode people’s trust in it or the medical products it approves.