An unexpected connection on LinkedIn. An offer of work from a headhunter, most likely a young woman, based in China. The chance to earn perhaps £20,000 part-time writing a handful of geopolitical reports for a Chinese company peppered with “non-public” or “insider” insights. Payment in cryptocurrency or cash preferred.

It may seem obvious, on this telling, that something about this approach would be amiss. Nevertheless, China’s powerful Ministry of State Security (MSS) still considers it worthwhile to deploy recruitment consultants to try it – leading MI5 to warn repeatedly about their activity online.

In 2023, MI5 chief Ken McCallum said Chinese agents were approaching Britons on LinkedIn on an extraordinary scale, at a rate of 10,000 over the preceding two and a half years, seeking political, industrial, military and technological secrets. But a fresh campaign aimed at politicians and parliament has led the spy agency to act again.

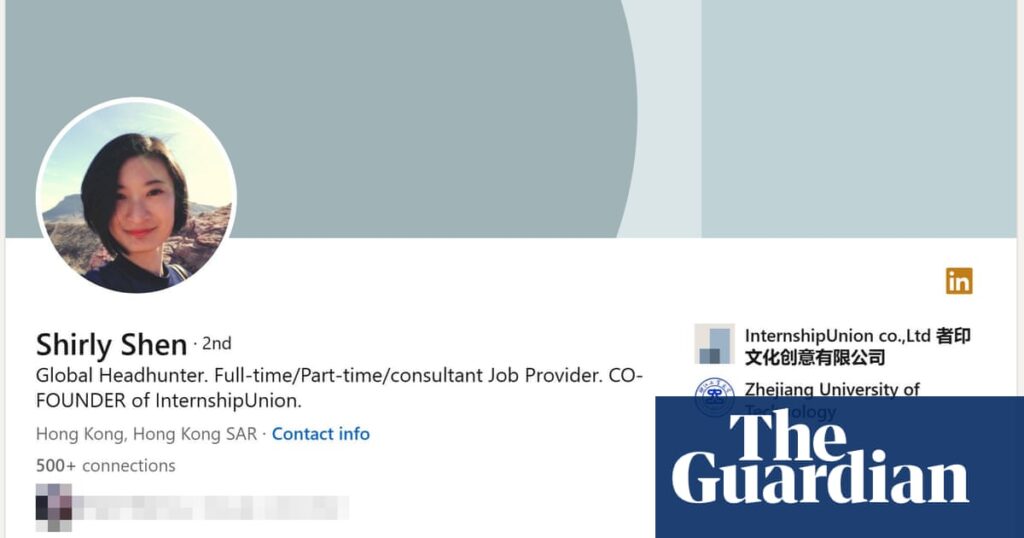

An espionage alert was issued on Tuesday via the offices of Lindsay Hoyle, the Commons speaker, and his Lords equivalent: a single slide after the repeated efforts of Shirly Shen and Amanda Qiu to contact MPs, peers, their staffers, economists, thinktanks – anybody who might become a source.

In the curious manner of British intelligence, there was no publication of the security advice from MI5 or the Home Office. But the agency knew its briefing note would leak once it was emailed out to parliament. Republishing it in the media helps the wider public better identify interactions with a fraudulent intent.

The alert has the effect of flushing out more information from in and around Westminster, though that is not MI5’s primary purpose. The agency wants people in public life to recognise that just because interactions on LinkedIn are not as toxic as on X or Facebook, it does not mean they are without risk.

Nor is the domestic spy agency understood to have been reacting to any specific incident in parliament, though the burst of activity does come after the embarrassing collapse of the prosecution of a former parliamentary aide Christopher Cash and his friend Christopher Berry on a technicality earlier in the autumn.

The two had been accused of spying for China – a charge they denied – but failure to complete a prosecution under the now repealed Official Secrets Act led to warnings that British democracy had been left unprotected.

The law has now been changed, and the MI5 slide contains a reminder of its replacement: “Those engaging in espionage activity risk significant criminal penalties under the National Security Act.” It is a crime if somebody engages in conduct that is or is likely to “materially assist a foreign intelligence service”.

An obvious question, though, is what Beijing has to gain. A politician who is not a government minister will have limited knowledge of classified material, and an associate of theirs less so. But Beijing is also interested in parliament: for a period, in 2020 and 2021, the UK’s China policy on issues such as Huawei or the Uyghur repression or genocide was being driven by MPs.

To a degree there are cultural differences too. Autocratic regimes like China’s export information gathering methods and the scale of its intelligence apparatus is vast, employing 300,000 people. Chris Inglis, a US national cyber director under president Joe Biden, said it was sometimes estimated that “the Chinese have more English speakers engaged in this than we [western intelligence] have English speakers”.

Beijing is willing to cultivate people over the long term and at times even the agencies have struggled to distinguish between legitimate relationships and espionage. “China has a low threshold for what information is considered to be of value,” security minister Dan Jarvis told MPs on Wednesday, but a sudden turn in the political cycle may mean someone rapidly peripheral becomes significant.

Another way to think about the relentless efforts at covert information gathering is in the wider context of the geopolitical contest between China and the west at a threshold below the level of outright war. China has stepped up its hacking efforts, with the Salt Typhoon penetration of phone and data networks in 80 countries, and the Volt Typhoon compromise of millions of internet devices.

Beijing is engaged in relentless efforts to find covert sources on British democracy online because it wants to be provocative, to display power and because it can.