Some Lactobacillus species are thought to be beneficial to the eye.Credit: SCIMAT/Science Photo Library

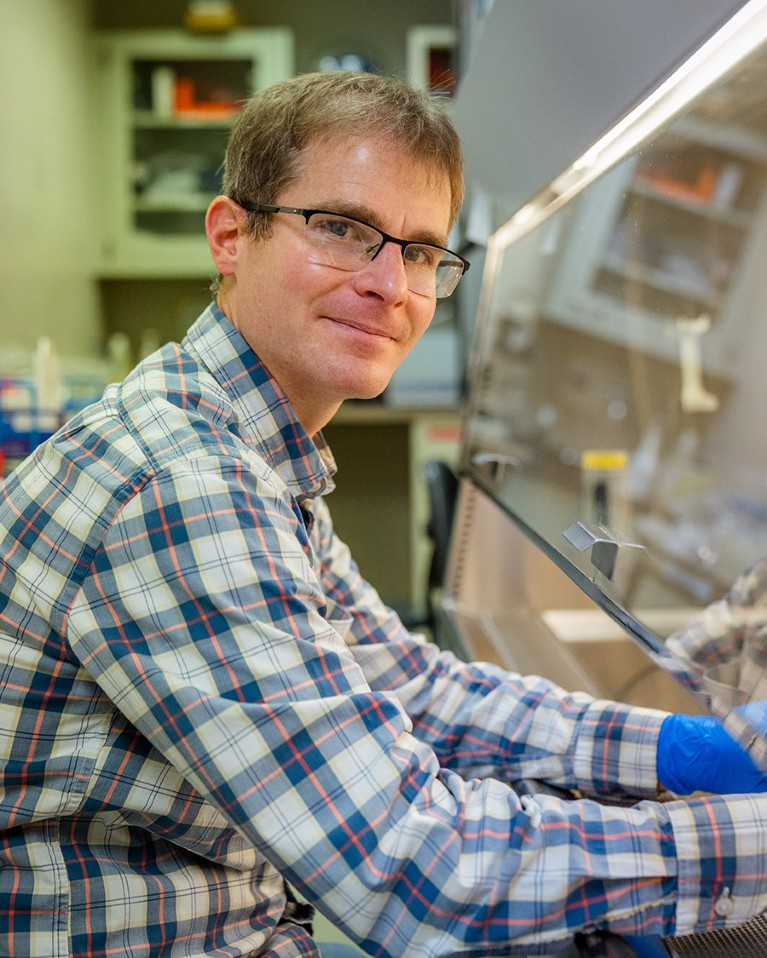

Science is full of happy little accidents, as Anthony St Leger and his research team have learnt. They were trying to study the microorganisms that live on the surfaces of the eyes of mice, but were having trouble getting the bacteria to grow in the laboratory. Then, there was a moment of serendipity. “We were culturing bacteria and we forgot a plate in a chamber,” explains St Leger, an ocular immunologist at the University of Pittsburgh in Pennsylvania.

Nature Outlook: The human microbiome

When the team discovered the plate a week later, the researchers found that a bacterium was growing on it. Initially, St Leger thought that the plate had been contaminated. But his team repeated the scenario from scratch, this time allowing the microbes to multiply for a week. Once again, the bacterium of interest — Corynebacterium mastitidis — grew.

The bacterium was simply slow-growing and needed more time to multiply. “I say that my whole research programme hinges on that one forgotten plate,” St Leger jokes.

For many years, the eyes were thought to be sterile. But dogged attempts to grow bacteria from tiny samples from around ocular surfaces — and advances in genetic sequencing that can deliver readouts of microbial DNA or RNA without the need to grow the organisms in dishes first — have shown that the eye has its own microbiome.

On the eye surface, there are only around 6 bacteria for every 100 human cells. By contrast, the human colon has an estimated 39 trillion bacteria — the highest density in the body. Some ophthalmologists call the eye ‘paucibacterial’, meaning little or few bacteria. Even so, microbes could have a marked affect on ocular health.

Some types of bacterium, such as Staphylococcus, Streptococcus, Propionibacterium and Corynebacterium, are emerging as influential members of the ocular microbiome. And considerable effort is being put into understanding how microbes in the gut and other areas of the body, affect ocular health. Together, these insights could pave the way for more effective treatments in a range of conditions, including painful dry eye and disorders that cause blindness, such as glaucoma.

Prime suspects

Researchers exploring the ocular microbiome focus mostly on the eye surfaces. These include the clear layer of tissue covering the white of the eye, called the conjunctiva, and the cornea, which covers the iris and pupil. Metagenomic analysis — an approach to sequence a vast range of microbes without culturing them in the lab — has been used to study the fluid inside the eyes, but scientists are still uncertain about whether populations of microbes, the microbiota, exist in that internal space. “Attempts to characterize an intraocular microbiome really, to date, haven’t yielded any convincing colonization,” says Russell Van Gelder, an ophthalmologist at the University of Washington in Seattle.

Anthony St Leger, and his team, identified a microbe in the eye.Credit: Eye & Ear Foundation

The identity and quantity of bacteria on the eye surfaces seems to influence the health of the human host. Some bacteria genera, including Staphylococcus, Corynebacterium and Lactobacillus, are thought to be beneficial. “In healthy eyes, they contribute to the stability of the ocular surface,” says Marco Zeppieri, an ophthalmologist at the University Hospital of Udine in Italy. If the microbiota becomes unbalanced — known as dysbiosis — then problems can occur. People with glaucoma, for example, have a higher presence of Pseudomonas and Acinetobacter in their eyes. This shift, Zeppieri says, could lead to inflammation and contribute to the progression of the disease, which increases pressure in the eye and can ultimately damage the optic nerve. And an overgrowth even of seemingly beneficial bacteria can lead to sight-threatening infections, such as microbial keratitis.

Dysbiosis of the ocular surface can also lead to blepharitis (a condition that causes swelling of the eyelids) and conjunctivitis. The latter can lead to scarring of the eye in severe cases and is commonly linked to viruses that can be detected in the ocular microbiome. “Most conjunctivitis, probably better than three-quarters in the United States, is viral,” Van Gelder says.

Van Gelder is part of an initiative, launched in 2023 by the US National Eye Institute, known as the Ocular Microbiome Project. This consortium of labs is working to understand the eye’s microbial environment. Using advanced sequencing techniques, Van Gelder and his collaborators characterized an adenovirus that they found in people with conjunctivitis, and studied the subtle genetic variability of that virus from person to person. “The short conclusion, which was completely unexpected to us, is that you could predict whose cornea was going to scar solely from the viral sequence,” he says. “The host didn’t matter.”

The ocular microbiome also includes fungi. And just as with bacteria and viruses, fungal dysbiosis can lead to serious eye disease. An infection of the cornea known as keratomycosis, for example, can be caused by an overgrowth of Aspergillus or Candida. Meanwhile, a lack of fungal diversity on the surface of the eye seems to correlate with worsening symptoms in conditions such as Sjögren’s syndrome — an autoimmune disorder that affects fluid-producing glands. People with the condition have dry eye, in which the ocular surface is not adequately lubricated by tears. “Their eyes burn and sting, and it drives them nuts,” Van Gelder says.

The bigger picture

Research into Sjögren’s syndrome has also revealed how microbiota elsewhere in the body can influence ocular health. “These patients have a different gut microbiome from healthy controls,” says Laura Schaefer, a microbiologist at Baylor College of Medicine in Houston, Texas.

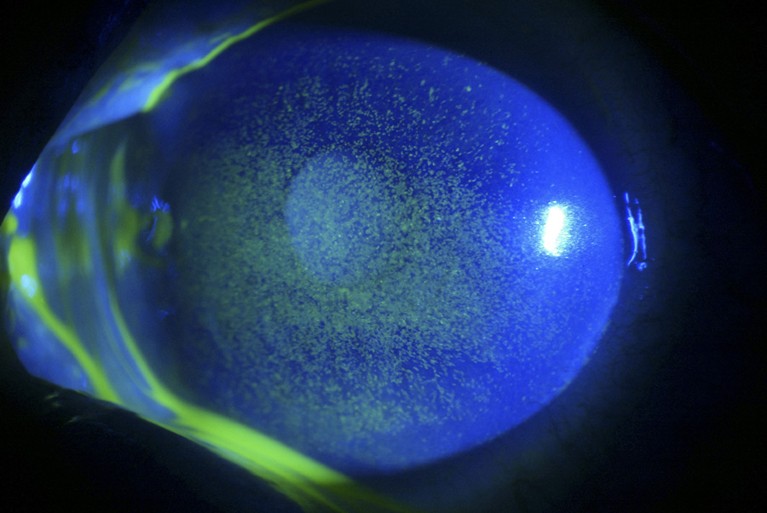

Dry eye can cause inflammation and ulceration (green) of the cornea and conjunctiva.Credit: Barraquer, Barcelona/ Science Photo Library

She and her collaborators explored the link between the gut microbiome and dry eye using mice raised in sterile conditions1. The lower digestive tracts of the mice were colonized with human gut bacteria using a fluid mixture with faecal content. Some of the rodents received gut bacteria from people with Sjögren’s syndrome, whereas others received those from healthy individuals. When exposed to triggers of dry eye, such as constantly blowing dry air, the mice with the microbes from people with Sjögren’s syndrome had greater signs of damage on the surface of their corneas than did the controls.

Schaefer and her colleagues aren’t yet sure how gut bacteria influence the integrity of eye membranes. One possibility is that molecular signals generated in the gut might cause immune cells to become overactive in other parts of the body, such as the eyes. Dry eye is also a feature of other autoimmune conditions, including lupus. A team including Zeppieri has suggested that the microbiome might contribute to this symptom in lupus, too2.

Researchers have proposed a mechanism by which gut dysbiosis contributes to the malfunction of intestinal barriers3. This enables bacteria and their metabolites to leave the gut and travel through the bloodstream or lymphatic vessels to the retina and optic nerve, potentially causing tissue degeneration and inflammation of nerve systems.

Van Gelder says that the gut dysbiosis link could be behind otherwise unexplained dry eye. Molecular tests on the tears of people with such symptoms, he says, show higher-than-normal levels of inflammatory markers known as interleukins and cytokines.

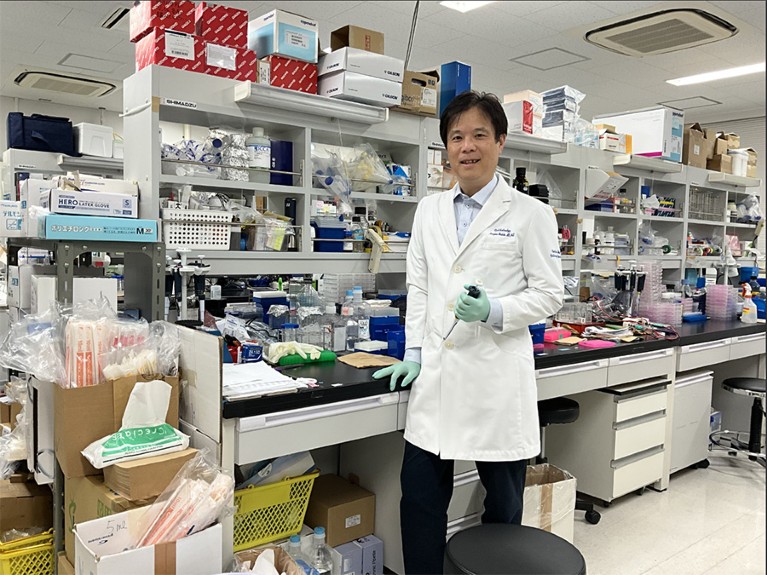

Dry eye affects around 10% of adults in the United States, and as many as 30% in other countries. Unravelling the mystery of it, therefore, is no small feat. “If you experience discomfort from eye strain or dry eyes, it can lead to a persistent feeling of being off all day,” says Noriyasu Hashida, an ophthalmologist at the University of Osaka in Japan who studies the eye microbiome.

The gut microbiome has also been implicated in age-related macular degeneration. The condition is a leading cause of blindness and affects around 200 million people worldwide. Although there have been conflicting results about which bacteria are more prevalent or depleted in the gut of people with the condition, researchers have found some correlations between inflammation-promoting bacterial changes in the gut and the eye condition4.

More clues about the connection between the gut microbiome and the health of the eye, known as the gut–eye axis, come from individuals with inflammatory bowel disease (IBD). Around 10% of people with IBD who develop symptoms beyond the digestive tract experience eye problems, including conjunctivitis, uveitis (inflammation of the middle layer of tissue of the eye) and episcleritis (inflammation between the eyelid and the white of the eye).

Some scientists are also investigating potential crosstalk between the lungs and eyes. For example, glaucoma and the lung condition chronic obstructive pulmonary disease share some underlying mechanisms, such as blood-vessel dysfunction and increased oxidative stress. Others are investigating whether the act of putting in contact lenses transfers bacteria from the skin to the surface of the eye or whether the lens material itself might alter the ocular microbiome.

Vision of the future

Discerning whether eye diseases are a direct result of ocular infections or are linked to microbe-induced inflammation — either in the eye or in other regions — could point to better therapies, Hashida says. Current treatments for eye conditions include lubricants, steroids, antivirals and antibiotics, all of which can cause side effects, as well as more invasive procedures such corneal transplants. But if specific microbial culprits can be identified for certain eye ailments, this could pave the way for therapies that treat the causes, rather than just the symptoms.

Noriyasu Hashida studies the eye microbiome.Credit: Noriyasu Hashida

One goal for researchers is to be able to find more molecular signals that link bacteria, viruses and fungi that reside on the eye to specific diseases that affect vision. Zeppieri explains that biomarkers of this nature could be useful for diagnosing, treating and managing eye disease, as well as preventing it to begin with.

If the Ocular Microbiome Project, which St Leger, Van Gelder and Schaefer are part of, can define the core microbial constituents of the eye microbiome, it will provide an essential reference framework for scientists studying vision-related disorders. But Zeppieri stresses that more research is needed to work out the roles of the microbes that have been identified.

Part of the mystery these scientists hope to unravel is how the eye maintains a healthy local environment. “How does a tissue that is fully exposed to the environment manage to not be massively colonized?” Van Gelder asks. Studies suggest that the eyes might get help from commensal microbes to fend off invaders by marshalling a first line of immune defence.

The bacterium that St Leger’s group identified through the serendipitous lab experiment, C. mastitidis, seems to be one such bacterium. “It’s fascinating that they actually found something that persisted on the eye, or at least the mouse eye,” Schaefer says.

In a mouse experiment, St Leger and his collaborators demonstrated that C. mastitidis induced immune cells in the eye’s surface tissue to release a molecule called interleukin-17. This messenger molecule prompted the recruitment of white blood cells to help fight infection, and caused the release of the antimicrobial ‘alarmin’ peptide into tears, which puts the immune system on alert for invaders. Ultimately, the presence of C. mastitidis protected the rodents’ eyes from infection when exposed to the pathogenic microbes Candida albicans and Pseudomonas aeruginosa5.

St Leger has set his sights on engineering eye-colonizing bacteria that are capable of delivering immunity-modifying molecules over the long term. His team has successfully genetically engineered C. mastitidis to secrete interleukin-10, which suppresses runaway inflammation and improves wound healing. In a preprint6, the team showed that this biotherapeutic microbe improved the healing capacity of mouse cornea.

St Leger thinks that biologists are learning so much about the eye microbiome that, in the future, they might be able to influence its composition. “You know how you take probiotics for your gut? We’re trying to create probiotics for the eye, essentially,” he says.

Schaefer and her colleagues have also explored the idea of probiotic treatments for eye disease. In 2023, they presented data at the annual meeting of the American Society for Microbiology showing that mice with dry eyes that consumed a ‘friendly’ strain of Limosilactobacillus reuteri bacteria had healthier and more intact corneal surfaces than did those that did not receive the probiotic. Schaefer notes that in other rodent experiments, a by-product of gut bacteria known as butyrate also seemed to help the eyes. “If you give our mice butyrate, which is a short-chain fatty acid, it’s protective of the ocular surface,” she says.

Although the eye isn’t host to as many microbes as the gut, scientists are learning more each day about their role in vision — and how best to harness this.