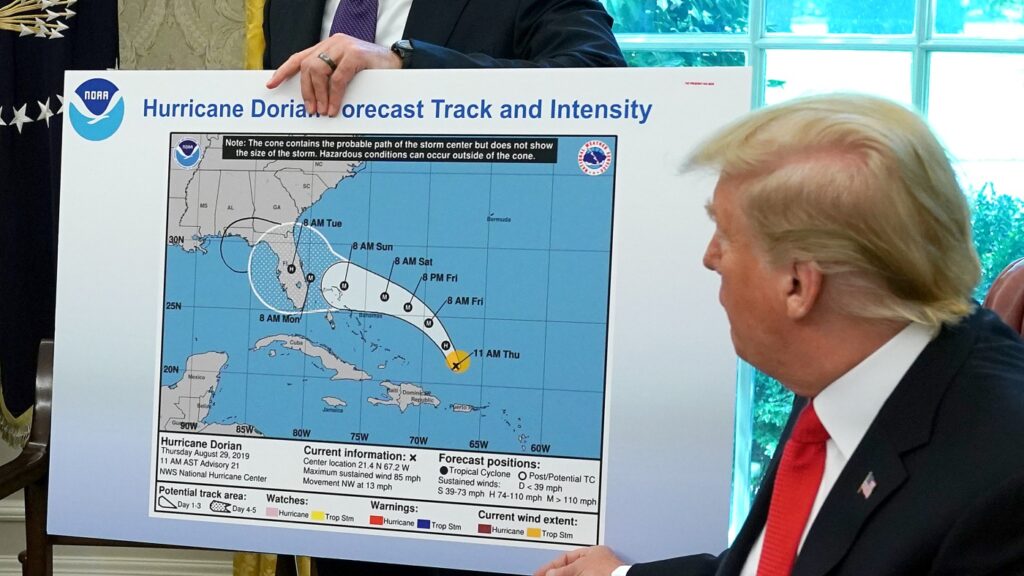

President Trump references a map while talking to reporters about Hurricane Dorian on Sept. 4, 2019. The map appears to have been altered by a black marker to extend the hurricane’s range to include Alabama.

Chip Somodevilla/Getty Images

hide caption

toggle caption

Chip Somodevilla/Getty Images

The White House plans to break up a key weather and climate research center in Colorado, a move experts say could jeopardize the accuracy of forecasting and prediction systems.

It’s the latest climate-related move by President Trump, who has called climate change a hoax, cut funding for climate research, and removed climate and weather scientists from their posts across the federal government. During his first term, Trump famously contradicted the nation’s weather forecasting service by redrawing a Hurricane Dorian’s path on a map with a Sharpie.

White House Office of Management and Budget Director Russ Vought, in a post Tuesday on X, announced the plan to dismantle the National Center for Atmospheric Research (NCAR) in Boulder, calling it “one of the largest sources of climate alarmism in the country.” NCAR was founded more than six decades ago to provide universities with expertise and resources for collaborative research on global weather, water, and climate challenges.

Vought said the center was undergoing a “comprehensive review” and that any “vital activities such as weather research will be moved to another entity or location.”

Antonio Busalacchi, who heads the University Corporation for Atmospheric Research, a nonprofit consortium of 129 U.S. universities that oversees the Boulder facility, told NPR he received no prior notice before the announcement and believes the decision “is entirely political.”

NCAR’s job is to study both climate and weather, and Busalacchi says the two cannot be understood separately. “Our job is to state what the science is, and it’s for others to interpret what the significance of that science is,” he says. “We’re very careful not to cross over that line to advocacy or policy prescription.”

Plan faces a political backlash

Vought’s announcement drew an immediate response from Colorado Gov. Jared Polis, a Democrat, who said in a statement that if the White House goes ahead with the plan, “public safety is at risk and science is being attacked.”

Sen. Michael Bennet, D-Colo., and Rep. Joe Neguse, a Democrat whose district includes Boulder, have suggested that the proposed NCAR closure amounts to political brinkmanship by the White House in response to Colorado’s refusal to release Tina Peters. Peters, a former Mesa County clerk, is serving a nine-year prison sentence for illegally accessing voting machines after the 2020 election. A Republican, Peters was recently pardoned by Trump, a largely symbolic action since she has neither been charged nor convicted in federal court.

“The judgement is that this is very much about Tina Peters,” Bennet told local media in Colorado. And that the president attempted to get his way through intimidation and he hasn’t gotten his way and he is trying to punish Colorado as a result.” In a joint statement, Bennett, Neguse and U.S. Sen. John Hickenlooper called the administration’s plan “deeply dangerous and blatantly retaliatory.”

NPR reached out to Vought’s Office of Management and Budget, but received no response. The White House press office did not answer specific questions, including one asking if “breaking up” NCAR meant it would be closed. But in a statement, the White House said “NCAR’s activities veer far from strong or useful science,” adding that the center was being dismantled “to eliminate Green New Scam research activities.”

American Meteorological Society President David Stensrud says he has used NCAR weather models throughout his career. “I think the work that I and others have done have led to the improvements that we see [in] … weather predictions,” he says. “Losing that [will cause] a great deal of hurt in terms of our ability to continue to improve forecasts and the future.”

The “beating heart” of climate and weather science

Among NCAR’s many contributions, in the 1960s, it developed dropsondes — tube-shaped instruments released from aircraft, including hurricane hunters, to measure temperature, pressure, humidity and wind. In the 1980s, the center helped develop and refine technology to monitor wind shear at airports.

Busalacchi says these efforts have contributed to decades without passenger plane crashes caused by wind shear or downbursts. “We’ve had zero loss of life from these weather events that can be directly attributed to our research. And that’s what we’re talking about losing” if NCAR shuts down, he says.

NCAR, which employs about 830 people, is also known for developing and maintaining tools such as the Weather Research and Forecasting Model (WRF), which is used around the world to predict everything from thunderstorms to large-scale systems, including hurricanes and frontal systems. NCAR’s Community Earth Systems Model (CESM) is also widely used by scientists, including Jason Furtado, an associate professor of meteorology at the University of Oklahoma.

Furtado says he and his colleagues have used the model to run experiments “to look for where in the atmosphere and ocean we get long-range signals for extreme cold air outbreaks” such as the February 2021 event that hit the midsection of the country, resulting in sub-zero temperatures for days and the total breakdown of the electrical grid in central Texas. “We’ve used [CESM] and come up with some really important research,” Furtado says.

He calls NCAR “a world-envied research center for atmospheric science” and “a beating heart for the atmospheric science community.” He says his research and that of many other scientists would simply not be possible without the Boulder center. “In some way every atmospheric scientist has a connection to NCAR, whether they’ve directly been to the building or they have not,” he says.

Ken Davis, a professor of atmospheric and climate science at Penn State, did research at NCAR from the time he was a graduate student until after his postdoc. He says NCAR plays a critical role in providing its members with cutting-edge computing resources, observational resources and scientific expertise “which no university can provide on its own.”

“If any investigator anywhere in the country wants to request a research aircraft … NCAR will take a look at that proposal and say, ‘Yeah, we can do that,’ ” Davis says. “As a university investigator, I can show up with an instrumented C-130 [aircraft] to do a whole bunch of airborne research, which would be totally impossible without this facility to support the community.”

This isn’t the first time the Trump administration has found itself at odds with the science community. In April, the administration dismissed scientists working on the country’s flagship climate report and then removed the report from a government website.

In 2019, Trump landed himself in a scandal known as “Sharpiegate,” in which he contradicted official National Weather Service forecasts for Hurricane Dorian by insisting the storm directly threatened Alabama. He later displayed an Oval Office map showing an altered storm path that appeared to have been drawn with a black marker. Earlier this year, the Senate approved the nomination of Neil Jacobs, a National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) official cited for misconduct related to the episode, to lead the agency.

In its 2026 budget plan, the White House has also proposed cutting NOAA’s budget by about 27% and eliminating NOAA’s Office of Oceanic and Atmospheric Research, the agency’s core climate and weather research branch. The administration has also rolled back National Science Foundation funding for climate science.

Ultimately, closing NCAR wouldn’t have an immediate impact on weather forecasting, Furtado says. Instead, he says, it would slowly erode the scientific community’s ability to make further progress on understanding weather and climate.

“We can either accept the facts and work on ways to mitigate and adapt, or ignore the data and not be ready for the changing world we have,” Furtado says.

“Having less accurate forecasts and being more in the dark about what is coming puts lives and property at risk,” he says.