Thirty years ago this week, two Swiss astronomers announced that they had spotted the first known planet orbiting a Sun-like star. The Nobel-winning discovery, later published in the pages of Nature, was the culmination of centuries of dreaming, and decades of searching, for worlds beyond the Solar System.

It was also the start of a whirlwind of discovery. Astronomers have since found more than 6,000 exoplanets, plus hints of thousands more. Many were detected by NASA’s Kepler and Transiting Exoplanet Survey Satellite (TESS) missions, with other telescopes also contributing (see graphic below).

The exoplanetary zoo hosts a diversity of beasts. There are ‘hot Jupiters’ that whirl closely around their stars, including the planet discovered 30 years ago, which is orbiting the star 51 Pegasi. There are ‘super-Earths’ and ‘mini-Neptunes’ — categorized because of how their masses compare with those of planets in the Solar System — which are some of the most common exoplanets found so far. There are systems crammed with multiple planets that move in almost musical rhythms with one another; rogue planets floating freely in the Galaxy; and alien worlds that circle two stars at once, just like the fictional Star Wars planet Tatooine.

On supporting science journalism

If you’re enjoying this article, consider supporting our award-winning journalism by subscribing. By purchasing a subscription you are helping to ensure the future of impactful stories about the discoveries and ideas shaping our world today.

“Each is a whole brand-new world, brimming with possibility and potential, usually unlike anything we’ve seen before and challenging our notions of what ‘normal’ planets and planetary systems look like,” says Jessie Christiansen, an astronomer at the California Institute of Technology in Pasadena.

Nature asked some astronomers about their favourite exoplanets — and got a wide range of suggestions.

Proxima Centauri: Nearby and visitable

At the top of many recommendation lists are the two — or possibly three — small planets that orbit Proxima Centauri, which is the closest star to the Sun — just 1.3 parsecs away in the constellation Centaurus.

The first Proxima planet was found in 2016 using the European Southern Observatory in Chile. It is probably Earth-sized and orbits within its star’s habitable zone, the distance at which liquid water could exist on its surface. A second confirmed planet lies just outside the habitable zone and is probably a little smaller than Earth.

The nearness of Proxima Centauri means that these planets are the best choices for an interstellar spacecraft to visit, says Jean Schneider, an astronomer at the Paris Observatory in France. The first effort to develop such a craft — a US$100-million project known as Breakthrough Starshot — has reportedly floundered.

Still, “before the end of the century we will go there,” Schneider says.

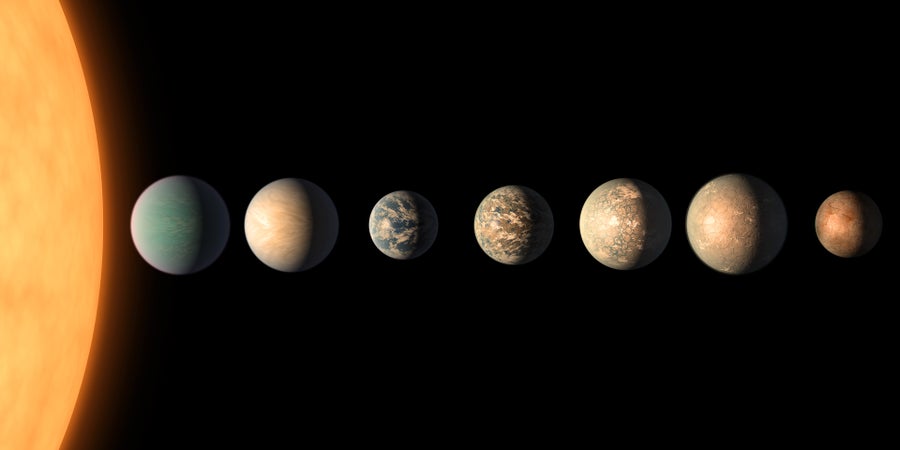

There are seven Earth-sized planets in the TRAPPIST-1 system.

NASA/JPL-Caltech/R. Hurt, T. Pyle (IPAC)

TRAPPIST-1: Earth worlds all in a row

Another favourite is the planetary system around the star TRAPPIST-1, which lies around 12 parsecs from Earth in the constellation Aquarius. Seven Earth-sized worlds orbit the star, discovered in 2016 and 2017.

Some of the TRAPPIST-1 planets lie in the habitable zone, making the system an ideal laboratory for exploring the evolution of Earth-sized planets at different distances from their star. The James Webb Space Telescope (JWST), in particular, has been scouring the TRAPPIST-1 planets for any sign of an atmosphere. So far, the news has been mostly negative — perhaps not surprisingly, because the star is extremely active.

But astronomers say there’s plenty to learn about the conditions that could lead to habitable conditions on some of the TRAPPIST-1 planets. Last month, for instance, astronomers using JWST reported that planet ‘e’ still has a chance of having an atmosphere.

“Plus, if you were on its surface, the other planets would look like moons in its sky,” says Néstor Espinoza, an astronomer at the Space Telescope Science Institute in Baltimore, Maryland. “Isn’t that just beyond sci-fi?”

K2-138: Musical resonances

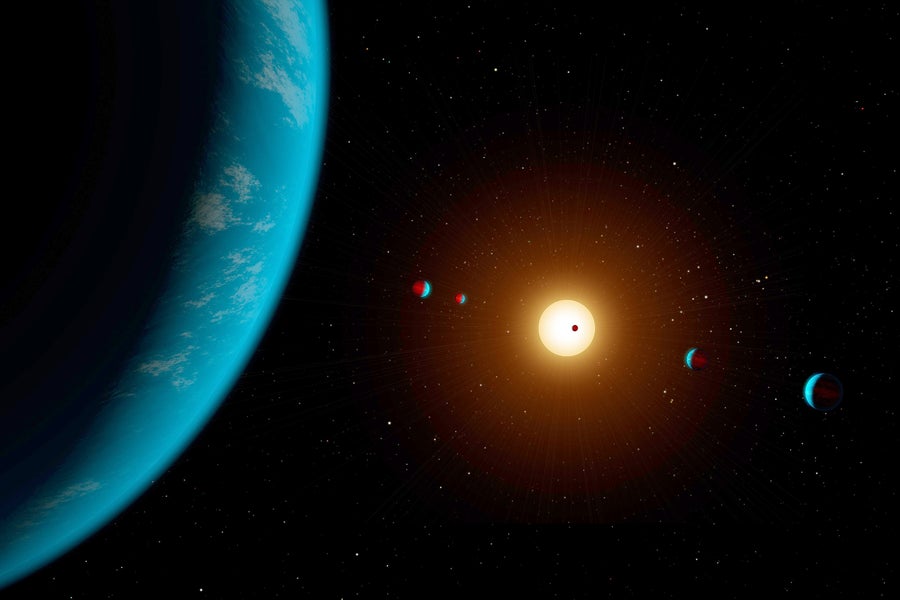

The planetary system K2-138 has six planets lined up around its star, around 200 parsecs away in the constellation Aquarius.

First discovered by citizen scientists who were trawling through data from NASA’s Kepler mission, the K2-138 planets move in a series of 3:2 resonances. That means that some planets orbit the star three times in the same time it takes others to orbit twice. Researchers have turned this resonance, which is similar to the perfect fifth interval in music, into a sonification of the planets.

The existence of the resonances suggests that the planets ended up in their final configurations through some slow, gradual process, Christiansen says. Many other planetary systems, including the Solar System, have experienced violent and chaotic reshuffling that destroyed such resonances. K2-138 thus preserves rare clues about the formation of planetary systems, she says.

The motions of the planets orbiting K2-138 can be converted into musical rhythms.

NASA/JPL-Caltech/R. Hurt (IPAC)

TOI-178: The power of multiple telescopes

Around 63 parsecs away in the constellation Sculptor lies a group of six planets packed tightly around their star, TOI-178. All six, if they were in the Solar System, would lie inside the orbit of Mercury, the closest planet to the Sun.

Theory predicts that such tightly packed systems could form when planets shuffle around a great deal during their early years. So the discovery of the TOI-178 system was “a great success of predictive theory”, says Christopher Broeg, an astronomer at the University of Bern in Switzerland.

The finding also underscores a common theme in exoplanet discovery: how multiple telescopes can work together to find, confirm and study planets. NASA’s TESS satellite was the first to spot signs of planets around TOI-178, but it took the European Space Agency’s Cheops satellite, which Broeg works on, to help confirm their details.

Kepler-47: Twin suns

It turns out that planets don’t have to orbit just one star. Astronomers know of at least two dozen ‘circumbinary’ systems, in which at least one planet orbits two stars.

Of these, the Kepler-47 planets are the favourite of Nader Haghighipour, an astronomer at the University of Hawai’i in Mānoa. The Kepler mission detected these three planets orbiting a pair of stars just over 1,000 parsecs away, in the constellation Cygnus. At least one of the planets lies in the habitable zone of both stars — although the chances of alien life there are tiny.

Still, the very existence of this system “confirms the idea that planet formation in circumbinary disks can proceed similar to that around single stars,” Haghighipour says. “That is a very important finding.”

This article is reproduced with permission and was first published on October 2, 2025.