For thousands of years traditional Chinese medicine (TCM) practitioners have checked patients’ tongues as part of a full examination, carefully scrutinizing their color, shape and coating in an attempt to detect illness. TCM considers a tongue’s color especially telling—and now some researchers, encouraged by recent studies pointing toward a measurable association with health factors, are working to adapt this ancient diagnostic approach to today’s AI-based technology.

TCM remains a controversial topic in the global scientific community. The World Health Organization officially added TCM diagnoses to the 11th revision of the International Classification of Diseases, the global standard for health-information classification, in 2022. But most high-profile studies have treated the topic warily. “Despite the expanding TCM usage and the recognition of its therapeutic benefits worldwide, the lack of robust evidence from the EBM [evidence-based medicine] perspective is hindering acceptance of TCM by the Western medicine community and its integration into mainstream healthcare,” wrote the authors of a 2015 review article on TCM’s prospects. Still, pockets of strong academic interest persist.

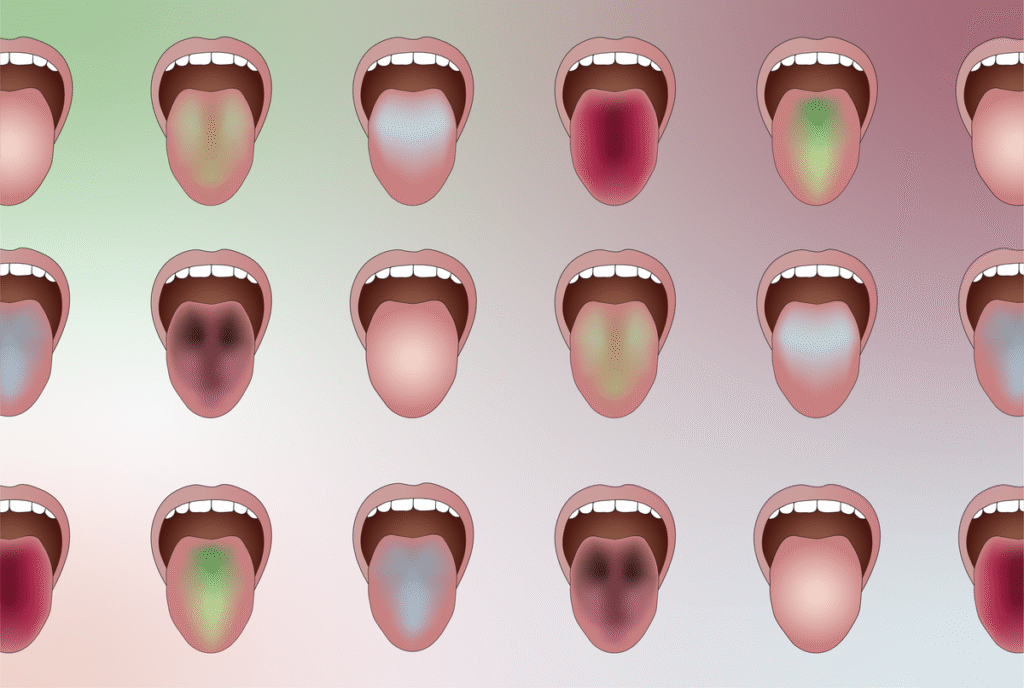

In TCM, tongue color “is closely linked to the condition of the blood and qi [a Chinese term often translated into English as ‘vital energy’], making it a primary indicator for TCM practitioners in assessing a patient’s overall health,” says Dong Xu, whose research at the University of Missouri focuses on computational biology and bioinformatics and who co-authored a 2022 study on analyzing digital tongue images. But tongue examination can be highly subjective: it relies entirely on an individual practitioner’s color perception and analysis.

On supporting science journalism

If you’re enjoying this article, consider supporting our award-winning journalism by subscribing. By purchasing a subscription you are helping to ensure the future of impactful stories about the discoveries and ideas shaping our world today.

Frank Scannapieco, a periodontist, microbiologist and oral biologist at the University at Buffalo, says that in Western medicine, no standardized clinical system is routinely used to monitor tongue features, although defined lesions on the tongue can serve as indicators for certain cancers—and some studies have linked tongue appearance to particular diseases such as breast cancer and psoriasis. Elizabeth Alpert, a dental health expert at the Harvard School of Dental Medicine, adds that tongue examination is often part of a routine screening for oral cancer by dentists and hygienists, but its accuracy depends on providers’ education and experience in clinical settings.

Massive developments in computing technology are causing some TCM-inspired medical researchers to take a new look at the tongue, however. The authors of a 2024 study in Technologies used machine-learning models to classify tongue colors and predict several associated conditions—including diabetes, asthma, COVID and anemia—with a testing accuracy of 96.6 percent.

A major challenge in previous tongue-imaging studies has been perception bias caused by varying light conditions, says the recent study’s co-author Javaan Chahl, a roboticist and joint chair of sensor systems at the University of South Australia. “There have been studies where people tried to [diagnose via tongue color] without a controlled lighting environment, but the color is very subjective,” Chahl says.

To address this issue, Chahl and his team developed a standardized lighting system within a kiosk setup. Patients placed their heads in a box illuminated by LED lights, which emitted a stable and controllable wavelength of light, and exposed their tongues.

Chahl and his colleagues collected 5,260 images—both real tongue photographs found on the Internet and additional color-gradient images. They used them to train machine-learning models to recognize seven specific colors (red, yellow, green, blue, gray, white and pink) at different saturation levels and in different light conditions.

The researchers confirmed that a healthy tongue usually appears pink with a thin white film; they found that a whiter-looking tongue may indicate a lack of iron in the blood. Diabetes patients often have a bluish-yellow tongue coating. A purple tongue with a thick, fatty layer could indicate certain cancers. COVID intensity (in people already diagnosed) can also influence overall tongue color, they found, with faint pink seen in mild cases, crimson in moderate infections and deep red in serious cases.

Next they applied the most accurate of six tested machine-learning models to 60 tongue images, all taken using the team’s standardized kiosk setup at two hospitals in Iraq in 2022 and 2023. They then compared the experimental diagnoses with the patients’ medical records. “The system correctly identified 58 out of 60 images,” says study co-author Ali Al-Naji, now a medical engineering professor at the Middle Technical University in Iraq.

Al-Naji is now working on narrowing the focus for diagnosis to the tongue’s center and tip. His group is also using a new tongue dataset of 750 Internet images to examine tongue shape and oral conditions such as ulcers and cracks with the deep-learning algorithm YOLO. Eventually Chahl would like to analyze more than just the tongue—perhaps the whole face.

Tongue color may possibly serve as a helpful biological marker of a person’s health state, but Xu cautions that it cannot stand on its own when it comes to making accurate clinical decisions. “The most fundamental limitation of current tongue-imaging systems is that tongue analysis represents only one component of a complete TCM diagnosis,” he says. And because image labeling is not widely standardized for this type of experiment, he adds, it’s harder to reproduce research findings.

The team has seen commercial interest in its system, Chahl says, but collecting usable data remains the biggest limitation to scaling up the research: “you need to have a lot of different people onboard with the process” to gather data with a kiosk in a large hospital, for instance, and to get consent to access patients’ medical records.

Scannapieco also highlights the challenges in standardizing tongue examination in a clinical or research setting. He says broad AI-based tongue analysis would require massive investment and huge databases of images and medical histories. “Until then, I think the field will develop by accretion of small studies that reveal correlations between tongue appearance and specific conditions,” Scannapieco says. “Of course, many diseases show no change in tongue appearance.” He adds that such a tool would be only one of many used for diagnosis.

Meanwhile online AI tools for tongue analysis have been quietly gaining popularity among consumers. Early this year Xu, his current Ph.D. student Jiacheng Xie of the University of Missouri, and their colleagues launched a GPT-based AI application, BenCao. Users can upload tongue images and receive personalized health guidance based on TCM concepts.

For now the app is designed and marketed only as a “wellness” tool, rather than a clinical diagnostic system, because giving out medical diagnoses requires far more caution. “We provide only some food and lifestyle recommendations,” Xie says. To bring it to the next level, his team aims to collaborate with clinical physicians, comparing the diagnosis outputs from machine-learning models and human doctors to identify the differences and performance gaps.