September 22, 2025

3 min read

Deep-Earth Diamonds Reveal ‘Almost Impossible’ Chemistry

Seemingly contradictory materials are trapped together in two glittering diamonds from South Africa, shedding light on how diamonds form

Yael Kempe and Yakov Weiss

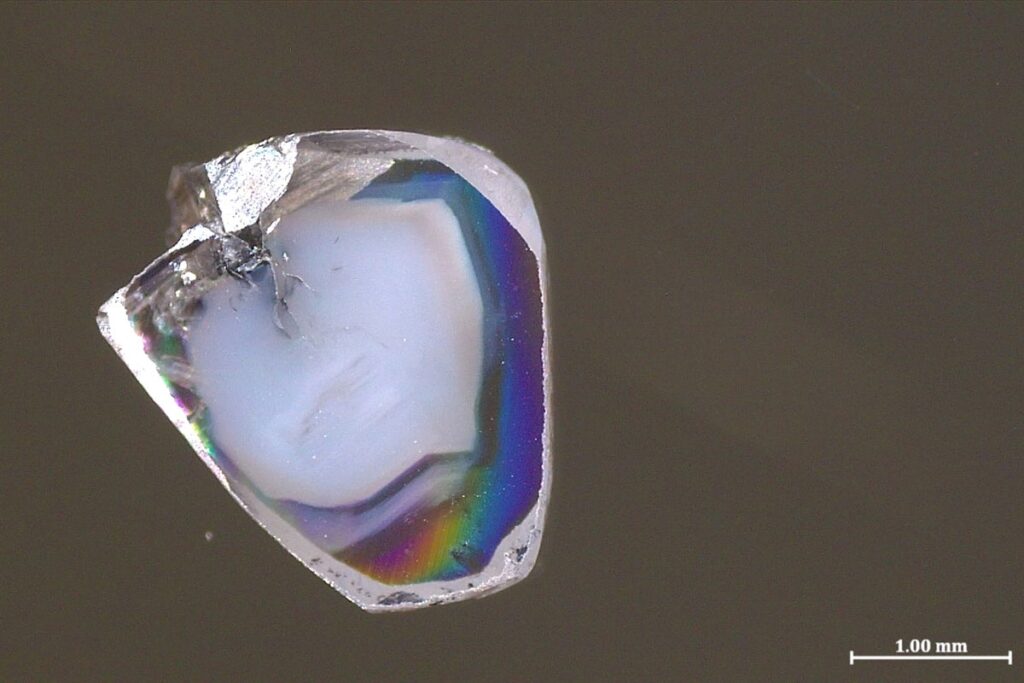

A pair of diamonds that formed hundreds of kilometers deep in Earth’s malleable mantle both contain specks of materials that form in completely opposing chemical environments—a combination so unusual that researchers thought their coexistence was “almost impossible.” The substances’ presence provides a window into the chemical goings-on of the mantle and the reactions that form diamonds.

The two diamond samples were found in a South African mine. As with plenty of other precious gemstones, they contain what are called inclusions—tiny bits of surrounding rocks captured as the diamonds form. These inclusions are loathed by most jewelers but are an exciting source of information for scientists. That’s especially true when diamonds form deep in the unreachable mantle, because they carry these inclusions basically undisturbed to the surface—the only way those minerals can rise hundreds of kilometers without being altered from their original deep-mantle state.

The two new diamond samples each contain inclusions of carbonate minerals that are rich in oxygen atoms (a state known as oxidized) and oxygen-poor nickel alloys (a state known as reduced, in the parlance of chemistry). Much like how an acid and a base immediately react to form water and a salt, oxidized carbonate minerals and reduced metals don’t coexist for long. Typically, diamond inclusions show just one or the other, so the presence of both perplexed Yaakov Weiss, a senior lecturer in Earth sciences at the Hebrew University of Jerusalem, and his colleagues—so much so that they initially put the samples aside for a year in confusion, he says.

On supporting science journalism

If you’re enjoying this article, consider supporting our award-winning journalism by subscribing. By purchasing a subscription you are helping to ensure the future of impactful stories about the discoveries and ideas shaping our world today.

But when they reanalyzed the diamonds, the researchers realized that the inclusions capture a snapshot of the reaction that made the sparkling stones and confirm for the first time that diamonds can form when carbonate minerals and reduced metals in the mantle react. The new samples are the first time scientists have ever seen the midpoint of that reaction captured in a natural diamond.

“It’s basically two sides of the [oxidation] spectrum,” says Weiss, the senior author of the new study describing the find, which was published on Monday in Nature Geoscience.

The find has implications for what lies in the mantle’s mysterious middle. As you travel deeper into the earth, away from the surface, the rocks and minerals become increasingly reduced, with fewer and fewer oxygen molecules available, but there is little direct evidence of this shift from the mantle.

Theoretical calculations have given researchers a notion of how the planet shifts from oxidized to reduced with depth. “We knew about that reduction with some empirical data, with real samples down to maybe 200 kilometers,” says Maya Kopylova, a professor of Earth, ocean and atmospheric science at the University of British Columbia, who was not involved in the new study but who wrote an editorial accompanying the paper. “What happened below 200 km [was] just our idea, our models, because it’s so difficult to get the materials.” There are only a few samples from below this depth, she said.

These new samples, which come from between 280 and 470 km below Earth’s surface, provide the first real-world fact-check on this theoretical mantle chemistry. One finding, Weiss says, is that oxidized melted material exists deeper than expected. Kimberlites, the erupted rocks that bring diamonds to the surface, are oxidized, so researchers had thought they couldn’t originate much below 300 km of depth. But these findings suggest that oxidized rocks occur deeper than that—and thus so might kimberlite rocks.

Diamond-forming reactions likely happen when carbonate fluids are dragged down by subducting tectonic plates, which bring oxygen-heavy minerals in contact with the metal alloys of the mantle, Weiss says. (Another way chemists think diamonds may form is by precipitating out of carbon-rich fluids that cool as they rise upward in the mantle, like sugar crystalizing from syrup. The new paper doesn’t rule out that process happening as well.)

The nickel-rich inclusions might also help explain an odd occurrence in some diamonds: occasional atoms of nickel seem to replace the carbon of these diamonds’ crystal lattice. That’s been a mystery, Kopylova says, because nickel is so much heavier than carbon that it shouldn’t be able to easily swap into the crystal structure. “Now, looking at these data, I see that it might be just a sign of diamond formation at certain depths,” she says. “That would be very interesting to investigate further.”

It’s Time to Stand Up for Science

If you enjoyed this article, I’d like to ask for your support. Scientific American has served as an advocate for science and industry for 180 years, and right now may be the most critical moment in that two-century history.

I’ve been a Scientific American subscriber since I was 12 years old, and it helped shape the way I look at the world. SciAm always educates and delights me, and inspires a sense of awe for our vast, beautiful universe. I hope it does that for you, too.

If you subscribe to Scientific American, you help ensure that our coverage is centered on meaningful research and discovery; that we have the resources to report on the decisions that threaten labs across the U.S.; and that we support both budding and working scientists at a time when the value of science itself too often goes unrecognized.

In return, you get essential news, captivating podcasts, brilliant infographics, can’t-miss newsletters, must-watch videos, challenging games, and the science world’s best writing and reporting. You can even gift someone a subscription.

There has never been a more important time for us to stand up and show why science matters. I hope you’ll support us in that mission.