Dear Marge,

You might have forgotten about the time your husband jeered at you on stage, as you spoke through a miniature wooden version of yourself. It happened in 1996, almost thirty years ago. Let me remind you of the circumstances.

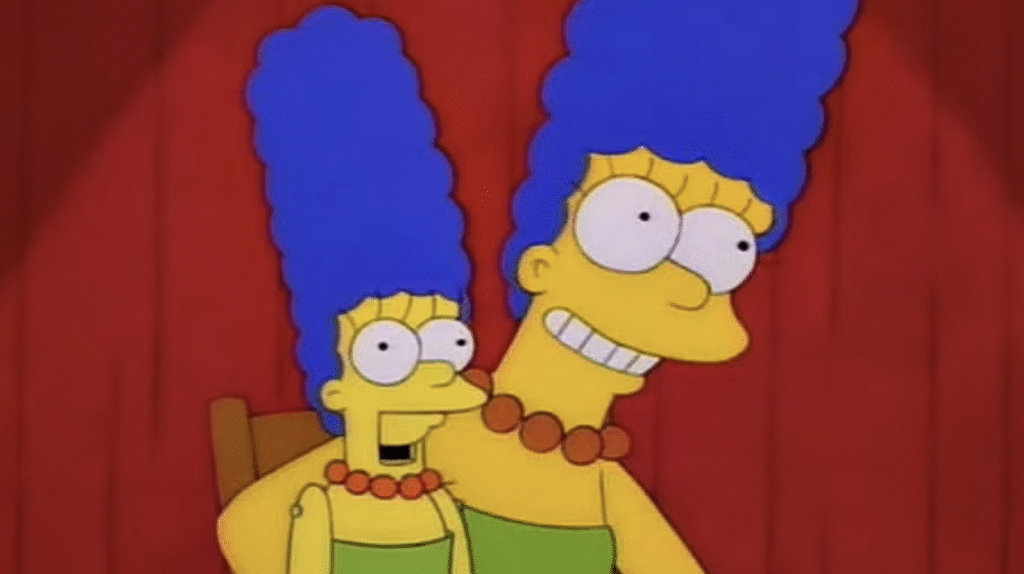

Your son, Bart, started working at a local burlesque house without you knowing. Upon finding out, you convinced the town of Springfield to tear down the risqué business at a town hall meeting—your righteous anger on full display. Right before an angry mob seized the house, the owner, Belle, and her dancers put on an Emmy-winning musical number (“We Put the Spring in Springfield”), which won over the crowd’s hearts, minds, and loins. Unfortunately, you—who showed up late and missed the song because you were renting a bulldozer—remained unconvinced. You tried to put your feelings into song, but you’re not a performer, and no one cared. Then you accidentally drove your bulldozer into the building, requiring you to pay for the damage one amateur ventriloquy show at a time.

Your ventriloquy show didn’t come through the happiest of circumstances. Still, it could have been a new chapter for you. A place to express yourself and make people laugh, to shake off those tired stereotypes of the begrudged wife, mother, and homemaker. But then your husband booed you, and, as far as I know, you never picked up ventriloquy—or performed comedy—again.

In 1996, I was ten years old. I didn’t understand what it meant to be married with children. I didn’t understand how it felt to have a husband who just wanted to watch TV at night after a long day of work. I didn’t understand the drudgery of cleaning the same peed-in car seat day after day. Nor was I familiar with the addictiveness of righteous anger, its scintillating bitterness. It took thirty years for me to relate to you, Marge. Someone whom I never wanted to relate to. You were so humorless, so full of goans. So unsexy—even in your strapless green dress. As a ’90s preteen, I wanted to be like Sabrina the Teenage Witch or Cher from Clueless. All blonde hair, crushes, and “baby girl” fashion. Not you, Marge Simpson. You wet-blanket of a woman.

It would take me thirty years to understand your context, Marge. The flawed euphoria of the mid-’90s. The dot-com bubble that wasn’t yet understood as a bubble. The notion that, with the fall of the Berlin Wall, the “end of history” had been reached. There were no more wars between superpowers. Quality of life was high! Racism and sexism were relics of the past! Never mind that there wasn’t a single woman on The Simpsons writing staff for the first six seasons—by which point your character’s identity had already been cemented. Your dourness was an instrumental foil that allowed Homer’s happy-go-luckiness, Lisa’s idealism, and Bart’s moxie to shine. “Marge’s pain,” a longtime Simpsons writer once told me, drove her plot. In the eyes of the writing staff, you and your pain were the same.

It would take me thirty years to question if the men who created you really understood you. Most of the first Simpsons staff writers were in their twenties and early thirties without families of their own. They worked twelve-hour days Monday through Friday, and sometimes weekends, without letting any partners or children down. Could they know what it was like to be a housewife? They imagined the slog of it, but could they imagine the joy? Did they know that when a toddler takes a dump on the deck when all their friends are over, that it’s not infuriating but hilarious. Could they imagine telling a kid not to bite the table, or stand on the counter, or take their shoes off at the park—that ‘it’s not funny’—before watching them laugh like the Joker as they do just that—makes a parent laugh too. That sometimes, at night, before a couple goes to bed, they giggle themselves to sleep as they recount every ridiculous thing their kid did that day. That, even when it’s painful, it’s not all pain.

Look, Marge, I’ll be honest with you. Your ventriloquy joke about Twiggy and Woody having a baby named “Chip” was not good. You can do better. I do, however, like that your ventriloquy doll is a mini-Marge. That’s very meta. You could work with that. Mini-Marge could be your “id,” saying all the things you’d never let yourself say. Like what you really want to be is a professional cuddler or NFT emotional support specialist. I don’t know. I’m not a comedian. This isn’t my bit. But I do know that comedy stars are not built overnight. It takes work and time and encouragement to hone those skills, especially when you’ve been pigeonholed as the bearer of pain. Of course, the episode you were in wouldn’t have been as funny if Homer had shouted something sincere and supportive, like “Needs work but keep going, honey!” Still, I like to imagine an alternate universe where Homer nurtured your burgeoning talent. I like to imagine that after your show, he brought you a bouquet of roses and told you he was proud of you for trying something new, for putting yourself out there.

I admit I’m doing some projection here. Lately, I’ve been trying on a new tone—in my art, my writing, my life. One that is more lighthearted. More laugh-out-loud. Instead of making art about rape or writing about past sexcapades in graphic detail, I’ve started collaborating with clowns, comedians, and even Simpsons writers. I want to make people laugh and smile more with my art because, thanks to motherhood, I’ve already found myself laughing and smiling more. And, when it comes to joy, shouldn’t the sky be the limit?

But I am nothing if not critical, mostly of myself. I’m looking at my joke batting average here with this piece, and it seems pretty subpar. “NFT emotional support specialist” strikes me as only moderately funny, as does making fun of my own intensity. My success rate, Marge, is probably not much better than yours. My husband would never “boo” me. But I have my own internalized Homer, telling me to give up. Telling me I’ll never be funny. Telling me I’ll always be this intense woman with a heavy heart and slightly ’90s fashion sense. That I should just go back to making rape art.

After all, look at the state of the world. Deadly floods and fires. Disappeared and murdered detainees. What is there to laugh about? But then I see my daughter, with her red Sideshow Bob curls, running around naked and gleeful, having recently pooped in front of all her friends, and I think there is hope. If that little clown can come from my body, if she can exist in this world, then I will fight for the right to a laugh-filled life.

Long story, short. If you are looking for an opening act, Marge, I hope you’ll consider me.

Sincerely,

Mieke Marple