November 1, 2025

5 min read

Can AI Music Ever Feel Human? It’s Not Just about the Sound

A personal experiment with the artificial intelligence music platform Suno’s latest model echoes a new preprint study. Most listeners can’t tell AI music from the real thing, but emotional resonance still demands a human story

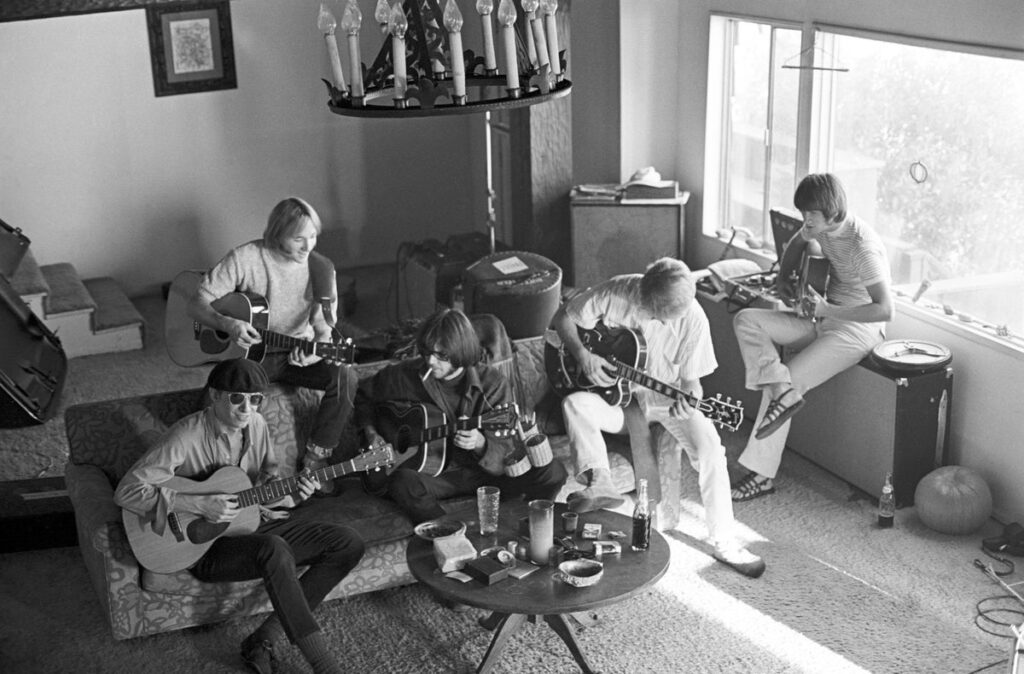

Superstar group “Buffalo Springfield” rehearse inside their house on October 30, 1967 in Malibu, California. (L-R) Bruce Palmer, Stephen Stills, Neil Young, Dewey Martin, Richie Furay.

Michael Ochs Archives/Getty Images

This week I logged on to Suno, an artificial intelligence music platform. I had just read a new study that found that most participants couldn’t distinguish Suno’s music from human compositions, and I wanted to try it for myself. I thought of a song that meant something to me—Buffalo Springfield’s “For What It’s Worth.” I’d first heard the tune when I was 17 years old, sitting in my stepfather’s kitchen in rural Virginia as he sang and strummed a guitar he’d made by hand. Released 30 years earlier, in December 1966, the song was a response to the Sunset Strip curfew riots—counterculture-era clashes between police and young people in Los Angeles. With my own guitar in hand, I’d set to learning the chords, trying to understand the feeling it had given me.

Now, at the computer, I prompted the AI to create a “folk-rock protest song, 1960s vibe … male vocals with earnest tone.” The generation took seconds.

With my headphones on, I listened, imagining myself in a cafe as the song came on the sound system. Though knowing it was AI-generated made me look for signs of artificiality, I doubted I could have distinguished it from a human-made song. And though it didn’t give me a frisson or make me want to play it on repeat, most songs don’t.

On supporting science journalism

If you’re enjoying this article, consider supporting our award-winning journalism by subscribing. By purchasing a subscription you are helping to ensure the future of impactful stories about the discoveries and ideas shaping our world today.

The paper on AI music, a preprint that has not yet been peer-reviewed, drew from thousands of songs on a Reddit board where users post Suno-generated music. The researchers then presented the study’s participants with pairs of songs and asked them to identify which of these tunes had been generated by AI. The team found that participants chose correctly 53 percent of the time—close to guessing—though when they were presented with stylistically similar human and AI songs, their accuracy reached 66 percent. But AI generation models update frequently, and by the time the study was released as a preprint, a more advanced Suno model was available.

Our relationship to music has changed in lockstep with technology. In a 2002 interview, David Bowie mused that everything about music would soon change. He predicted the transformation of its distribution and the disappearance of copyright. And to emphasize how easy it would be to access, he said, “Music itself is going to become like running water or electricity.” That hardly seemed to be a prophecy. Napster, the music sharing platform launched in 1999, had already opened the taps with electronic music sharing and piracy, making music distribution easier than ever. Then, in 2003, the iTunes store began selling songs at 99 cents a pop, and in 2008 Spotify’s monthly subscription service opened the taps even wider. Since 2023 Suno has contributed to the volume of music shared online. Spotify recently announced that, over the past year, it removed 75 million “spammy” music tracks to maintain the quality of its offerings, though it is unknown how many, if any, of the removed tracks were created with Suno.

But even as AI music improves, I can’t help but wonder how it will fit into our lives. I grew up with mixtapes, the precursors to playlists, made for workouts, road trips or simply sharing. They were built up from songs that either I or my friends loved. I can’t imagine someone handing me a thumb drive of AI-generated tracks and saying, “There are infinitely more where these came from!”

Yet history teaches us not to underestimate how a few ingenious humans can harness new technology to express themselves. In the 1970s, as disco DJs extended and edited songs for the dance floor, remix culture was born. In the 1980s, hip-hop artists sampled funk, soul and rock songs to create new tracks. I grew up hearing people call sampling lazy and liken it to theft; a federal judge opened a 1991 landmark sampling opinion with the biblical quote “Thou shalt not steal.” When Danger Mouse spliced Jay‑Z and the Beatles into The Grey Album in 2004, the music label EMI sent cease‑and‑desist letters. Fans, however, staged “Grey Tuesday” to distribute the mash-up in protest. We now recognize art in the edit, and DJs have moved from the corner to the marquee.

But DJs have always had a relationship to their music—they sample songs they love. Although one might argue AI (which also has copyright issues) is trained on music humans love, we can’t easily feel that connection; the most we can really say is that it has, in a sense, a terroir.

I struggle to see how AI music will win us over. By 2015 and 2017, research was already showing that people couldn’t distinguish between human- and computer-made music. And years earlier, in 1997, composer and computer pioneer David Cope created music software. An audience that heard a pianist play its output alongside a piece by Johann Sebastian Bach thought the software’s composition was the actual Bach.

So while it’s reasonable to fear that talented musicians might never be heard because millions who don’t play an instrument or sing are flooding the Internet with AI songs, I suspect most AI music will, like most other music, be forgotten or never noticed. Even with exceptional human music, we want more than virtuosity—an origin story, a connection. Similarly, a few rare, extraordinary AI songs will no doubt be attached to cultural moments—movies, videos, memes—or will be created by AI-music studios that give people more control over the output than text prompts can and that may allow for the creation of more innovative and personal songs.

This isn’t to say that we shouldn’t be cautious of musical machines. A decade after player pianos and phonographs entered mass production in the 1890s, composer John Philip Sousa warned that amateur musicians would disappear and people would become “human phonographs.” The fear wasn’t misplaced. Historically, many families made music together, and that tradition has faded. Whereas parents and children used to play in the living room, teenagers now sit alone in their bedroom and blast songs on headphones. In comparing music to electricity, Bowie was speaking of a similar loss. He said musicians should be prepared to do a lot of touring, implying that live performance would be the only way to create genuine connection with audiences—“that’s really the only unique situation that’s going to be left,” he added.

When my stepfather taught me to play “For What It’s Worth,” he was sharing a song he first heard on the radio when he was nine years old and that, at age 11, he’d learned to play by listening to a vinyl LP he’d bought for a couple of dollars. These days I hear the song often in coffee shops and yoga classes—it’s back in vogue, as good a fit for today’s social concerns as it was in 1966—and I notice it every time, not for its melody or lyrics or virtuosity but for its story.