If you’re trying to get someone to do something, what’s the best way to achieve that? Paying them probably comes to mind, and this intuition is a basic tenet of economic theory. In a massive 2018 study, researchers tested 18 ways to motivate people to do a simple task—and found that money worked best.

In that work, economists at the University of California, Berkeley and the University of Chicago asked nearly 10,000 people on a crowd-work website to push the “A” and “B” buttons on their keyboard as many times as they could for 10 minutes. To motivate people, the researchers used different strategies with different participants. They gave some people more money if they pushed the buttons more times. They gave other people nudges—essentially, messages or framings that serve as small psychological pushes. For instance, to instill a social norm about working hard, the economists told some participants that many other people pressed the buttons more than 2,000 times. As another example, some people saw how their score compared with that of others, which prompted social comparison and competition.

The result was a blowout. Paying people beat out nudging them in every case. Even just a little bit of money, such as an extra penny for 1,000 button pushes, motivated workers more than every psychological nudge.

On supporting science journalism

If you’re enjoying this article, consider supporting our award-winning journalism by subscribing. By purchasing a subscription you are helping to ensure the future of impactful stories about the discoveries and ideas shaping our world today.

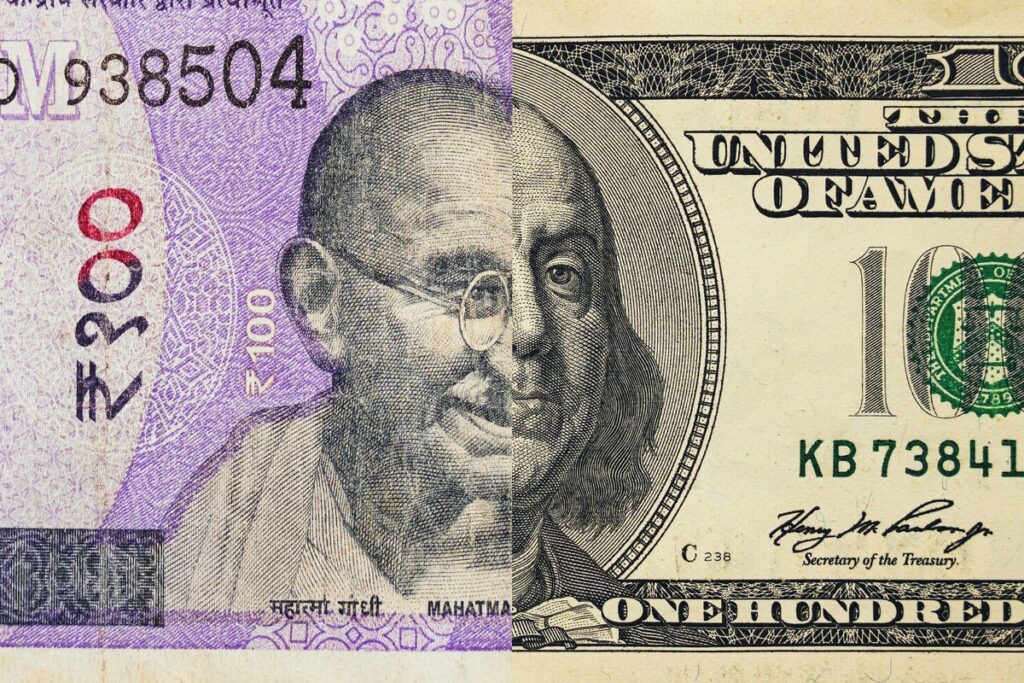

But as a cultural psychologist, I couldn’t help but wonder whether that was the end of the story. The majority of the study’s participants were located in the U.S., but 12 percent were in India. I wondered whether money was an equally dominant motivator in both places. That question led my colleagues and me on a multistep journey across cultures and, ultimately, to new data that suggest cash may be more persuasive in the West than in more collectivistic cultures outside the West.

Thanks to the researchers of the 2018 study, who shared their data with me, I was able to take a closer look at their findings. I found that the behavior of participants from India looked very different from that of people in the U.S. In one of the scenarios tested, the researchers had some people work to earn money for themselves and other people earn money for charity. In the pay condition, workers received 10 cents for every 1,000 times they pushed the buttons. In the charity condition, those 10 cents went to the Red Cross. According to classical economics, people should work hard for their own pocketbook but slack off when that money is going to charity. And that described American participants quite well. Button pushes in the U.S. dropped 14 percent when money went to charity versus to participants. But in India, it made almost no difference—there was a decrease of less than 1 percent.

The plot thickened when I looked at the nudges. Giving people a social norm (by telling them how many times other participants pressed their buttons) influenced them, just like psychology says it should. But doing so had more power in India. Providing a social norm boosted button presses by 19 percent in the U.S. and 26 percent in India. Across 11 different conditions, money outperformed psychology by about 20 percent in the U.S. but only by 10 percent in India.

Why would money influence people in the U.S. more than in India? One possibility is that more Americans have studied economics, which teaches people to behave more like economists say they should. There is in fact some evidence that people in econ classes behave more “rationally”—that is, selfishly—in games where researchers ask people to make choices about earning real money versus being nice to other people. Another explanation is that the U.S. is an especially capitalistic culture, which, some people argue, makes people hyperfocused on money and competition. The movie Jerry Maguire embodied that image of American culture when its eponymous character, played by Tom Cruise, shouted into the phone, “Show me the money!”

But my research team thought these cultural differences were broader than a story about American cultural uniqueness. We thought a deeper explanation might reflect what psychologists call “relational mobility.” In cultures with lots of relational mobility, social ties are free and flexible, with lots of choice and opportunities to meet new people. In cultures with less relational mobility, relationships are binding and fixed, with an emphasis on stability and commitment rather than freedom and choice. People in individualistic Western cultures, such as those of the U.S., France and Australia, tend to describe their relationships as free and flexible. One byproduct of this dynamic is that, in the West, work often revolves around clear expectations and explicit exchange. If you work one hour, you get one hour’s wage. Growing up in the U.S., I learned this lesson at home when my parents paid me an allowance for washing the dishes a specific number of times each week.

Research suggests that explicit exchange and contracts are probably less important in “low-mobility,” collectivistic cultures. Sure, India, China and Mexico—all more collectivist than countries such as the U.S. and U.K.—have plenty of contracts and wage labor. But people there tend to feel more enmeshed in their relationships than Americans or Brits do. And those relationships—even at work—bind people together in fuzzy ways that aren’t outlined perfectly in contracts. That could explain why, when I looked through data from the study, I found that participants in India worked harder in response to a social norm, to social comparison (“We will show you how well you did relative to other participants”) and even to a simple request to “please try as hard as you can.”

We reasoned that, if our hypothesis was correct and this difference reflected a broader cultural difference, we should be able to find differences in other cultures beyond the U.S. and India. So my research team tested a new task on people in Western, individualistic cultures in the U.S. and U.K., as well as in more collectivistic ones in India, Mexico, China and South Africa. Again, money spoke louder in the West, as we reported in Nature Human Behaviour. For example, money outperformed psychological nudges by more than 100 percent in the U.K. but only by about 20 percent in China.

This difference is especially surprising because the same dollar buys more in India and Mexico than in the U.S. or U.K. And because incomes are lower in South Africa and China, basic economic logic predicts that they should work harder for that same dollar. But that wasn’t the case.

One thing we worried about was whether the differences came down to trust. Did our participants in the West simply trust the scientists and payment system more than people in other nations? Our data suggested that trust was not the explanation. For example, we asked our participants whether working hard on the task could help build a relationship with us and lead to more earnings in the future. Our participants in more collectivistic countries were more likely to agree. That investment of time and effort only makes sense if they have some trust in us and the platform.

One problem with comparing people in different nations is that it involves comparing different environments as well as psychologies. After all, the U.S. and South Africa have structural differences. For example, the two countries have different gross domestic products and average Internet speeds. And we found more participants in South Africa than in the U.S. completed the task on their phones. If we compare countries, it’s hard to know whether the differences are caused by what’s in people’s heads versus what’s in their environments.

To isolate the psychological differences, we randomly assigned more than 2,000 people in India to complete our study in English or Hindi. India does not have a single national language, but Hindi and English are both official languages. We recruited our participants through Ashoka University, which is in Haryana, a primarily Hindi-speaking part of the country. Much of India’s university system teaches in English, so people wouldn’t bat an eye if our study instructions popped up in either language. We also selected participants who reported very good or fluent language skills in both languages. When the instructions were in Hindi, we expected this would cause a subtle frame shift that would emphasize Indian culture and embedded relationships. And conversely, we guessed that English might prompt thinking in terms of how relationships are structured in Western culture.

Sure enough, language changed the power of money. The sway of monetary payments over nudges was about twice as large in English as it was in Hindi. So even in the same economy, money spoke louder in English.

Our findings raise many interesting questions about rationality and ethics. First, despite the tendency in classical economics to talk about “rational actors” and how people should behave, what’s rational depends on the social environment. If explicit contracts are more important in one culture, it makes more sense to read the contract carefully and ignore the polite request to “try hard.” But in cultures where relationships matter more, it makes more sense to pay attention to social cues.

On the flip side, our findings probably give ammunition to critics of the U.S.’s obsession with money. But as with biases more broadly, identifying patterns in behavior that are shaped by culture is empowering. It may make us more aware of our own tendencies, for example.

Understanding money’s power also has implications for development aid and the growing “nudge” movement, which tries to find subtle ways to change people’s behavior using psychology. Our study used trivial tasks, such as mashing buttons on a computer. But people often use money or nudges to motivate changes that are good for society, such as donating organs or saving electricity. Understanding culture can make us better at making our world a better place.

A recent study found that a nudge to change social norms about female entrepreneurship in Niger was enough to boost household income as much as giving people money—and it cost far less. Our findings suggest that psychological nudges may be most effective in the places they help people the most.

Are you a scientist who specializes in neuroscience, cognitive science or psychology? And have you read a recent peer-reviewed paper that you would like to write about for Mind Matters? Please send suggestions to Scientific American’s Mind Matters editor Daisy Yuhas at dyuhas@sciam.com.