Stay informed with free updates

Simply sign up to the Film myFT Digest — delivered directly to your inbox.

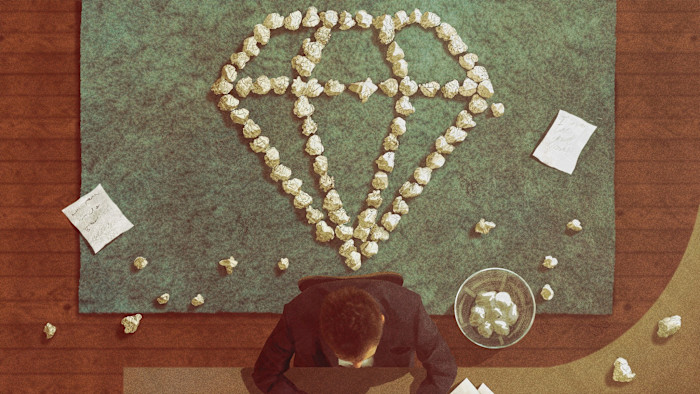

Charles Dickens’ A Christmas Carol is a story about the value of kindness and Christian compassion. Brian Henson’s The Muppet Christmas Carol is the same story, with an added parable: about the risks of excessive studio meddling. The film’s cinematic cut is maligned among cinephiles. Disney’s studio chief at the time, Jeffrey Katzenberg, asked Henson to excise the song “When Love is Gone” after children in test screenings grew bored during it. The result is that Belle and Ebenezer Scrooge’s split is startlingly abrupt. As a compromise, the song was reinstated for the film’s release on home video.

As a child watching at home, I found “When Love is Gone” boring, just as the various jokes riffing off Dickens’ original went over my head. Now, I prefer the home release version to the cinematic cut (and my favourite gags are those that reference the original text).

So who was right, Henson or Katzenberg? I’m inclined to side with the producer. A great family film — like The Muppet Christmas Carol, Toy Story, Frozen or KPop Demon Hunters — should include enough in it for viewing adults to enjoy, whether they are watching it with their kids or looking back to their past. But its primary audience is children and I am therefore inclined to side with my easily-bored younger incarnation and Katzenberg and leave “When Love is Gone” on the cutting room floor.

Ultimately, there isn’t a right or a wrong call. Among film lovers, it is fashionable to side with the director over the studio. But recent years have, I think, shown us that the worried producer, the margin-cutting suit, and indeed the editor, are the unsung heroes of almost any creative endeavour.

Very few “director’s cuts” are as necessary or well-put together as Blade Runner — most are flabby messes like Donnie Darko. Without someone demanding that Lena Dunham’s stories fit into neat slots between commercial breaks, you don’t get a bigger and better version of Girls — you get the aptly named Too Much.

Absent a penny-pincher asking whether the movie really needs that third act fight or yet another showdown involving lots of CGI, you get the average Marvel movie. (And so many of them are so very average.) It’s got to a point where occasionally, when sent a preview link, I have the urge to risk prison by hacking the file, editing it down myself and sending it back to whichever streamer — and even the best of the crop, Apple TV, is prone to flab — with a note saying “there. I fixed it”.

Nor is this problem confined to the screen. With a handful of exceptions, one of the modern horror stories of our time is when a favourite writer leaves a “legacy” publication to go at it alone: the result is almost always that their thoughts are less sharp, less well edited and less readable than what went before, when they worked with collaborators and editors. (It’s not a coincidence, I think, that so many of the best Substack writers pay for their own editors, or have had a long career writing for magazines or organisations that prize editing.)

It’s not to say that the suits are always right: it was Warner Brothers who wanted to stretch The Hobbit films over eight hours, and Warner Brothers again that wanted to contort the seven Harry Potter books into eight movies. When there is a demand for more, both the corporate desire for greater revenue and the creative desire for greater expression can form a doom loop of a kind. (Just look at the incredibly lucrative changes that George Lucas has made to the original Star Wars films — while each amendment made them flabbier and sillier, each new release enjoyed bumper sales on video, DVD or BluRay.)

The demand that TV and films be written to accommodate audiences who are “second screening” — that is to say, they are watching something on one screen, and doing something else on another — means that far too many movies released this year had dialogue with enough heavy-handed exposition to serve as a radio play. No one appears to have had the inclination, or the internal clout, to cut back on bloated running times.

Nevertheless, it is the case that creativity thrives with constraint and collaboration, that we work better within constraints, and that everyone, even the most successful of directors, benefits from strong editors and nervous producers. It isn’t just my Christmas viewing that would be improved if 2026 turns out to be the year in which the editors strike back.

stephen.bush@ft.com