Unlock the Editor’s Digest for free

Roula Khalaf, Editor of the FT, selects her favourite stories in this weekly newsletter.

Data centre developers are turning to aircraft engines and fossil fuel generators to power the AI boom, as supply chain shortages and long waits to connect to the grid delay cheaper and cleaner alternatives.

Manufacturers of aeroderivative turbines — which are based on or made from jet engines — and diesel generators have reported increased demand because of data centres seeking to bypass the grid as they wait for larger gas turbines.

“The incentives have never been greater for any sort of technology that can supply power,” said Kasparas Spokas, director of the Clean Air Task Force’s electricity programme.

The need for on-site energy is booming as data centres face wait times of up to seven years to connect to the grid, as well as a backlash over their impact on utility bills. By installing power sources such as aeroderivative turbines and generators next to their data centres, developers can power the training and running of their artificial intelligence models without the immediate need for a grid connection.

GE Vernova is supplying data centre developer Crusoe with aeroderivative turbines that are expected to produce nearly 1 gigawatt of power for OpenAI, Oracle and SoftBank’s Stargate data centre in Texas.

Ken Parks, GE Vernova’s chief financial officer, told investors in December that the company was seeing “growing demand” for its aeroderivative and smaller gas units, which “serve as bridge power supporting data centre needs”.

Orders of the company’s aeroderivative turbines rose by a third in the first three quarters of 2025 compared with the previous year.

ProEnergy has sold more than 1GW of its 50 megawatt gas turbines directly adapted from jet engines. While the company is increasingly making parts from scratch, it also uses CF6-80C2 engine cores, which are found in Boeing 747s.

“We can deliver more quickly than bigger original equipment manufacturers,” said Andrew Gilbert, partner of Energy Capital Partners, ProEnergy Holdings’ majority investor. “The ability to find a few hundred megawatts to get started with, and then grow over time is useful too.”

Sections of the economy seemingly outside of the AI boom are pivoting towards power to pick up revenue.

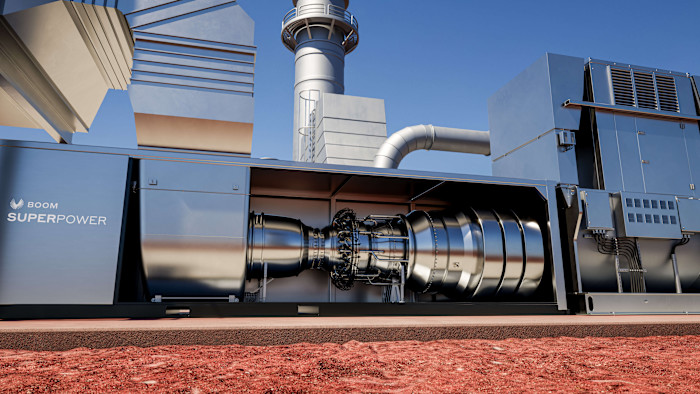

Sam Altman-backed aviation start-up Boom Supersonic announced a deal to sell to Crusoe turbines that are expected to provide 1.2GW of power and are “virtually identical” to those built for its jets.

Boom Supersonic intends to use earnings from power turbines to help fund its jet business.

“Three or four years ago I imagined we would do the airplane first and energy second,” chief executive Blake Scholl told the Financial Times. “But then I got a call from Sam Altman who said: ‘Please, please, please make us something.’”

The use of generators fuelled by diesel and gas is also increasing. Manufacturer Cummins has sold more than 39GW worth of power to data centres and nearly doubled its capacity this year.

While generators are often used by data centres as backup power, Cummins’ data centres executive director Paulette Carter says they are seeing “growing interest in on-site primary power”.

Energy secretary Chris Wright has suggested commandeering existing backup generators to fortify the grid, telling Fox News in November: “We will take backup generators already at data centres or behind the back of a Walmart and bring those on when we need extra electricity production.”

The use of generators has prompted concerns over emissions, since smaller power sources tend to be less efficient.

While local and federal regulators place limits on when backup generators can be used, these are being loosened in response to data centre demand. In Virginia, where “data centre alley” is located, the Department of Environmental Quality is considering allowing data centres to run diesel generators more often, while the Environmental Protection Agency said data centres could use generators to maintain stable power.

“In almost all cases I can imagine, emissions are going to be much worse for data centres powered by on-site fossil-based generation, relative to sourcing power from the grid derived from efficient gas generators and renewables,” said Mark Dyson, electricity managing director at the Rocky Mountain Institute.

However, the cost of on-site power is likely to be higher than a simple grid connection, since such arrangements miss out on the economies of scale that utilities enjoy. Analysts at BNP Paribas modelled the price of power at a behind-the-metre gas plant Williams Company is building in Ohio, for which Meta will be a customer. The result was $175 per megawatt hour, which is roughly double the average cost of electricity for industrial customers.

The rush for power may also die down when hyperscalers slow their capital spending.

“We’re in a very strong market right now, but it won’t stay like that forever,” said Mark Axford of Axford Turbine Consultants.