In which an artist discusses making a particular work.

– – –

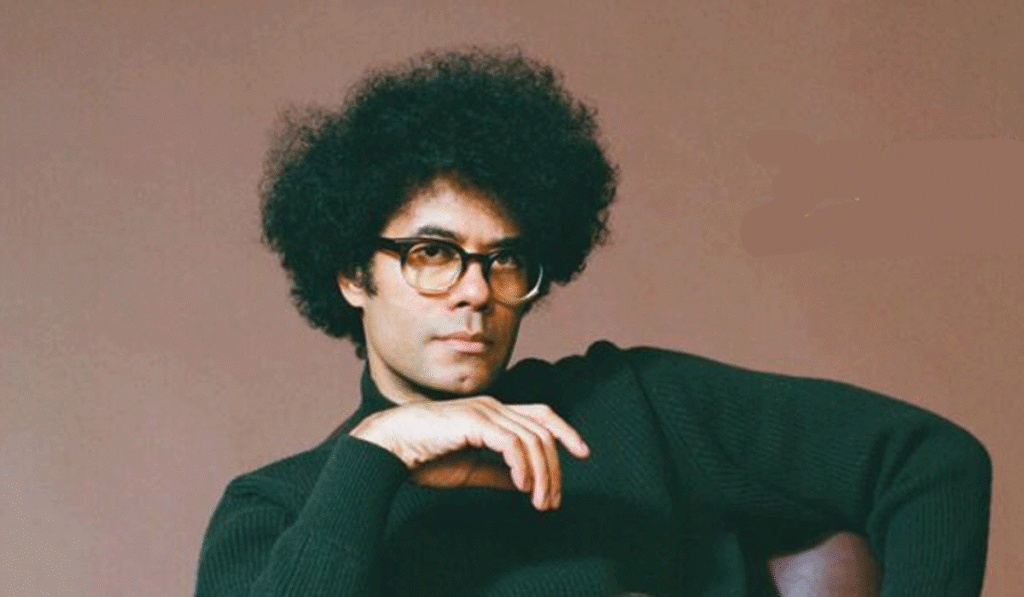

I met Richard Ayoade, the brilliant British author of The Unfinished Harauld Hughes, which is out in paperback this September from Faber, because (possibly through some misunderstanding) he asked me to appear as an actor in his 2013 film, The Double, a contemporary take on the disturbing early novel by Dostoyevsky. Unlike Dostoyevsky, Ayoade became a well-known comedian and character actor before he was thirty. And also unlike Dostoyevsky, he was almost immediately seen to be so charming, so enjoyable, so magnetic and companionable, that he was summoned to be the host of many television programs. Among other programs, Ayoade worked as the host of a humorous weekly travel show and a series about different, unfamiliar but clever gadgets, as well as many comical game shows. Behind the scenes, he’s also directed music videos and provided voices for cartoons. Before The Double, he directed the delightful and sensitive 2010 film Submarine, featuring Sally Hawkins and Paddy Considine.

I found Ayoade, as a director, to be unfailingly polite, considerate, amusing, and amused. He didn’t seem to be agitated by the innumerable surprises and difficulties that inevitably arise in the process of making a film. His demeanor was relaxed, almost languid. But he did turn out to have a steely, determined side, and I did personally find it close to impossible to respond in an adequate manner to his relentless insistence that all of his actors should speak very, very quickly, as this was a key feature of the forceful style of the film. I came to realize only later that this sped-up dialogue actually mirrored the normal pace at which Ayoade’s brain functions on a daily basis. And I came to understand that it was this faster-than-normal human brain speed that explained the seemingly impossible fact that while engaged in game shows, gadget shows, cartoons, and whatever, Ayoade was at the same time sharpening his skills as a writer. By my count, he now has nine books in print.

The character referred to in the title of Ayoade’s latest fiction—the grand and imperious Harauld Hughes—is himself a writer. And, of course, many writers have invented characters who are writers—but do you know any other writer who has not only invented a character who is a writer but who has then gone on to actually write and publish that imaginary writer’s complete works? Richard Ayoade has done that, and if you take out your Kindle and look up Harauld Hughes, Faber will be glad to send you Hughes’s collected plays, poems, prose pieces, and screenplays, all in fact written by Richard Ayoade. And you wouldn’t call Hughes an unusually prolific author, but before his unfortunate ( fictional) death, Hughes did a not inconsiderable amount of writing, representing a perfectly respectable life’s work. So inevitably, one has to be curious about what Ayoade was up to here. Was this all just a joke? I’m not aware that there’s ever been a joke of this length. Are these works parodies? But there are no originals of which they could be parodies, as Hughes never really existed. And they don’t in fact resemble the work of any other writer, so they’re clearly not parodies. What are they, then? If I had the ability to do so, I would love to summon a great international conference of professors of English literature to try to answer this question. I myself am stumped, because sentence by sentence, line by line, Hughes is a wonderful writer who makes no mistakes, while page by page one does have the impression that Ayoade is being “funny” rather than “serious,” except that rather frequently a page will suddenly appear that seems (perhaps almost by mistake?) to be “serious” rather than “funny.” Which brings us to the question of the meaning of these concepts or words, “serious” and “funny,” which is a question that’s both dealt with indirectly in different sections of The Unfinished Harauld Hughes and is also a question raised by the book as a whole, a question that Ayoade and I circled around when we talked to each other on the telephone several months ago.

— Wallace Shawn

– – –

WALLACE SHAWN: So in this very hilarious book, The Unfinished Harauld Hughes, you, Richard, are the narrator, and you’re the central character, in a way. And you seem to be a rather bumbling person whose occupation is that of a “presenter.” In the book, you’re trying to film a documentary about a much greater person, Harauld, who is no longer alive—a playwright and screenwriter who initially fascinates you because when he was alive, he looked just like you. Now, to begin with, I’m an American, so I’m not familiar with this word presenter. We don’t use that word. What is a presenter? Is it just a word for a sort of traveling moderator? Someone who goes to different places or different events and presents them to a television audience? Someone who just appears on a show about a chess tournament in New Zealand and says, I’m here in New Zealand, and this is—

RICHARD AYOADE: Yes, well, in this context, where the show is a documentary (although I have heard people use the term docu-tainment with a straight face), the presenter is someone who appears and who is in effect saying, Come this way, look at this… And so in the book I was asking, Well, what if this rather trivial person who appears on things—myself—is trying to find out about this more profound person? He’s wondering, How can I, with my sort of trivial concerns, access this person who seems to be free from them?

WS: And so, in speaking with you for The Believer, I believe I’m allowed to ask why you wrote your book the way you did, because in Harauld Hughes you’ve created a character who looks like you but who takes himself very, very seriously. He’s pompous and pretentious. And you make an awful lot of fun of him. He seems to be a sort of alter ego, someone who you might be but who you aren’t, and you do mock him quite severely. Now, I myself happen to be a playwright and screenwriter who takes himself very, very seriously, so I took this personally, and I wondered why you mocked your alter ego so severely. It certainly seems to bother you a lot that he has no sense of humor, certainly not about himself. I don’t know if I have a sense of humor myself anymore, but I know that when I was a boy I did, and when I was a boy I was what was called the class clown. Actually, we had two class clowns in my class, because Chevy Chase was in my class, and he was also the class clown, but he was much more daring than I was, and in order to be funny, he would take the risk of enraging the teachers, which I didn’t do. Were you the class clown when you were a boy?

RA: No, I don’t think so. Not that there’s a contradiction between being a class clown and being studious, but I think I was more studious, and I think I probably was more interested—and there are quite a few funny people I know like this—I think I was more interested in music. In fact, wasn’t Chevy Chase quite interested in music? I think he was. Was he a drummer?

WS: Yes, I think at one time he was, and a keyboard player. And in school, when the teacher would play a long phrase on the piano and ask us to sing it back to him, the rest of us could sing the first three notes or whatever, and Chevy could sing the whole phrase.

RA: He’s got great rhythm to his speech, brilliant timing. It’s strange to me to be talking about humor, because I don’t think it’s anything I expected to be involved with at all. In so many of the projects I’ve done, I’ve felt there was another person in it who was the funny person. Even at school, there were many funny people who I just liked being around and hearing them be funny. At college one of the first people I met was John Oliver—and we wrote sketch comedy together. I felt I was more like someone who wrote material that John Oliver would then deliver, even though we were, I guess, in what we called a double act. I think I was keener for him to do the bulk of the performing. I’ve always liked making things, and sometimes it’s almost more convenient to be in them than to not.

WS: I have to say, there are many pages in your book that are, you know, wonderful pages that you would find in a wonderful novel. You write quite beautifully and insightfully not only about the process of making films but even about human feelings, the love between men and women. Your female characters are marvelously vivid. The relationships are complicated and interesting. And obviously most novelists have a sense of humor—if you think of even Dostoyevsky, or Jane Austen, Muriel Spark, et cetera, et cetera—but, well, they have a kind of commitment to, I don’t know what: naturalism? And in your book, you stick with a kind of naturalism for maybe two pages, but then you’ll introduce something that’s so farcical that the naturalistic element is completely disrupted, and you’re no longer in the realm of what would be called a novel. It’s pure quote, unquote “humor,” or I don’t know what you want to call it. I mean, is that simply how your mind works? Or…

RA: Well, there are some people, like, say, Ingmar Bergman, where I would say nothing he has ever produced has been funny at all. I know some people say Smiles of a Summer Night is witty, but I just… Now, All These Women, which was his first color film and was meant to be funny—I remember seeing that and having a thought that I shouldn’t have been proud of, which was, I’m funnier than Ingmar Bergman!

WS: I think you are!

– – –