September 4, 2025

5 min read

Kids from Marginalized Communities Are Learning in the Hottest Classrooms

The first national study of its kind shows that children from marginalized communities are more exposed to extreme heat events

A fan moves air around in a third-grade classroom in Denver, Colo., on October 8, 2024.

RJ Sangosti/MediaNews Group/The Denver Post via Getty Images

A heat wave can turn a classroom without proper cooling into an oven. Excessive heat can interfere with the learning process of any child—but in the U.S., the students who are most affected are disproportionately from low-income families and communities of color.

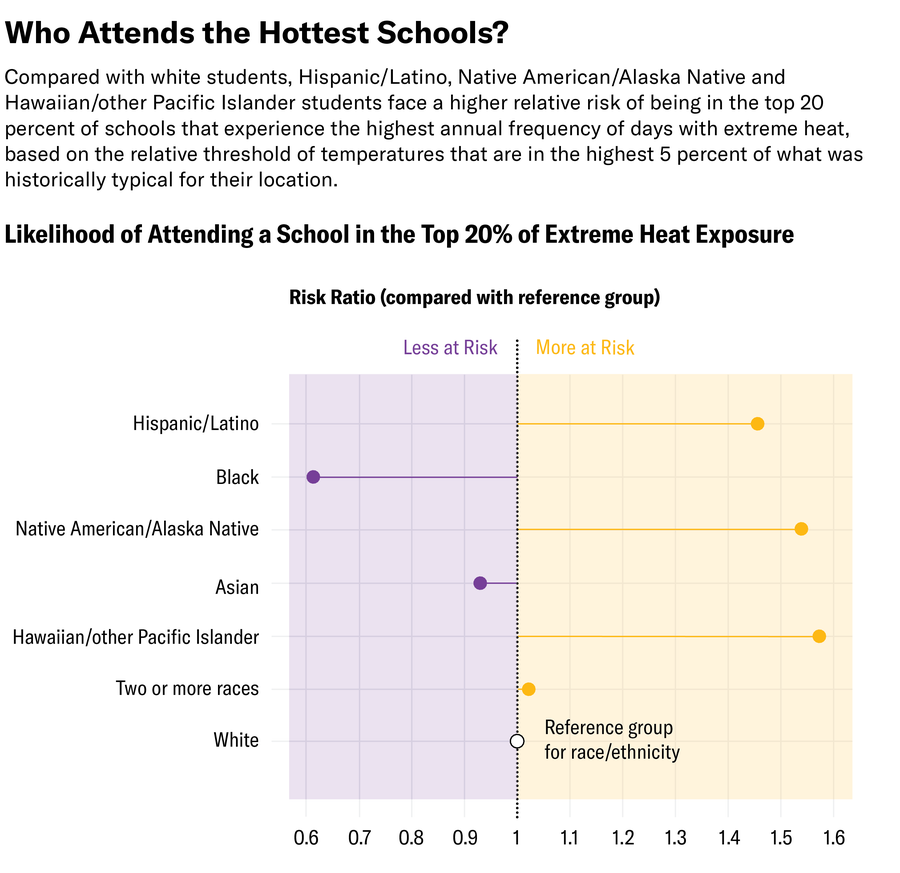

A recent study published in SSM Population Health has now quantified these inequities across U.S. public schools for the first time. Researchers found that Hispanic/Latino, Native American/Alaska Native and Hawaiian/other Pacific Islander students, along with children who are eligible for free or reduced-price lunch, are significantly more likely than their white and wealthier peers to attend schools located in places that experience the highest number of days with extreme heat .

“This is information that we probably could have concluded without the data,” says study co-author Sara Soroka of the University of California, Santa Barbara. “But we’re hopeful that this study can be used to create and implement policies to mitigate children’s heat exposure as the frequency and intensity of extreme heat events continue to increase.” Because of rising global temperatures caused by burning fossil fuels, heat waves in the U.S. are happening more often, lasting longer and spreading into spring and fall. Although it is well known that people from minority racial and ethnic groups are generally more exposed to heat than people in white and wealthier communities, there has been no data on how disparities in exposure play out in schools.

On supporting science journalism

If you’re enjoying this article, consider supporting our award-winning journalism by subscribing. By purchasing a subscription you are helping to ensure the future of impactful stories about the discoveries and ideas shaping our world today.

To measure the disparities, Soroka and her co-author mapped temperature data onto every public school in the contiguous U.S. They defined extreme heat in two ways: an absolute threshold of days in which the outside temperature was above 90 degrees Fahrenheit (32 degrees Celsius) and a relative measure of the days when temperatures were in the highest 5 percent of what was historically typical for a given location. Such a relative measure is useful because, for example, Dallas sees temperatures above 90 degrees F for most of the summer months; higher temperatures are far less common in, say, Seattle. Places where hot temperatures were historically rarer often have schools that lack air-conditioning.

The researchers then ranked schools nationally and identified those with the highest frequency of days with extreme heat. Then they compared the demographics of students attending those high-heat schools with students in cooler environments.

The results showed that Hispanic and Native American/Alaska Native students were overrepresented in the schools that were most exposed to prolonged heat or extreme heat events. The researchers also found that low-income students—defined as those eligible for free or reduced-price lunch—were disproportionately concentrated in those same schools.

The researchers didn’t find Black students to be overrepresented in schools facing the highest number of extreme heat days under the relative measurement, but these students were overrepresented in schools that experienced the most such days under the absolute measurement, based on the threshold of 90 degrees F. Soroka says this reflects the higher concentration of Black and low-income students in places across the South—where summer temperatures regularly surpass 90 degrees F but days hotter than the local average are less common. The authors also note that Black students are less represented in schools in the Northeast and Midwest. In both regions, changes in the occurrence of extreme heat events have been more noticeable, and schools have been less likely to have cooling systems in place.

The findings are consistent with other studies showing that “redlined” neighborhoods—places that have historically been discriminated against and neglected when it comes to public services—are generally hotter than wealthier neighborhoods because of a lack of green areas, air-conditioning and heat-resistant buildings, says Ladd Keith, director of the Heat Resilience Initiative at the University of Arizona. “Heat is actually the number one weather-related killer in the United States, and it has only been recognized, really, as a hazard in the last couple of years,” Keith says. “The fact that it compounds all of these other social inequities in an invisible way, to many people, is one of the most dangerous things about it.”

The new study did not account for the existence or quality of air-conditioning equipment in schools where extreme heat is common; public data on this is severely lacking. But the U.S. Government Accountability Office estimated in 2020 that about 36,000 schools across the country needed to replace or upgrade their HVAC (heating, ventilation and air-conditioning) systems. This problem tends to affect schools that historically had little exposure to heat and were therefore not designed to accommodate large cooling systems, Keith says.

With global temperatures and extreme heat events consistently rising across the country, schools will have to monitor changes in temperature and adapt, Keith says. But he notes that “the schools that are financially strapped are going to have more difficulty upgrading their air-conditioning units—and even starting them for the first time—without state or federal support.”

How Heat Affects Learning

Studies have shown that heat reduces children’s ability to learn, decreases their productivity and exposes them to risks such as heatstroke and dehydration. At the same time, school closures caused by extreme heat affect children’s access to education—and even to meals, for those who receive free or reduced-price lunch. There is no available data on how often U.S. schools close because of extreme heat, but UNICEF estimates that in 2024 about 242 million students in 85 other countries or territories had their education disrupted by extreme climate events, including heat waves.

And heat exposure does not end at school for many children from low-income families and communities of color, says Amie Patchen, a public health researcher at Cornell University. “Kids in lower-income communities that are more likely to be in schools without air-conditioning are also more likely to go home to places without it.”

Patchen says that the new study highlights the double vulnerability of children in marginalized communities and that such data is important for designing more research focused on inequities in air-conditioning access, as well as heat-resistant infrastructure in schools.

Even though the National Integrated Heat Health Information System (a federal governmental information system to help policymakers protect people from heat) and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention recognize children as an at-risk group when it comes to heat, there are no national policies guiding schools on how to respond beyond canceling classes during heat waves.

Children in cities face the highest risk because of the urban heat island effect, which causes city temperatures to be higher than in surrounding suburban and rural areas. This effect means school authorities in affected areas must be especially careful in monitoring temperature changes, says Kristie Ebi, a global health scientist at the University of Washington.

For Keith, school authorities and local and state governments must take protective measures to prevent disasters like the Pacific Northwest heat dome of 2021—an extreme weather event that caught local governments and schools across the region largely unprepared for the unprecedented heat. Keith notes that outdoor sports continued during the early part of the heat dome until local officials realized the severity. But some students had already been exposed to the dangerous temperatures amid school-sanctioned events.

Until there is a national strategy to improve the conditions of schools and better ensure children’s safety, Keith says, local governments need to learn from mistakes and experiences elsewhere. “My advice,” he says, “is to learn from the places that have been caught off guard and do your proactive planning before it happens to you.”