Stocks soared on Friday following the strongest signal yet that US the Federal Reserve is gearing up to start cutting interest rates again this fall. But how long this celebration can last?

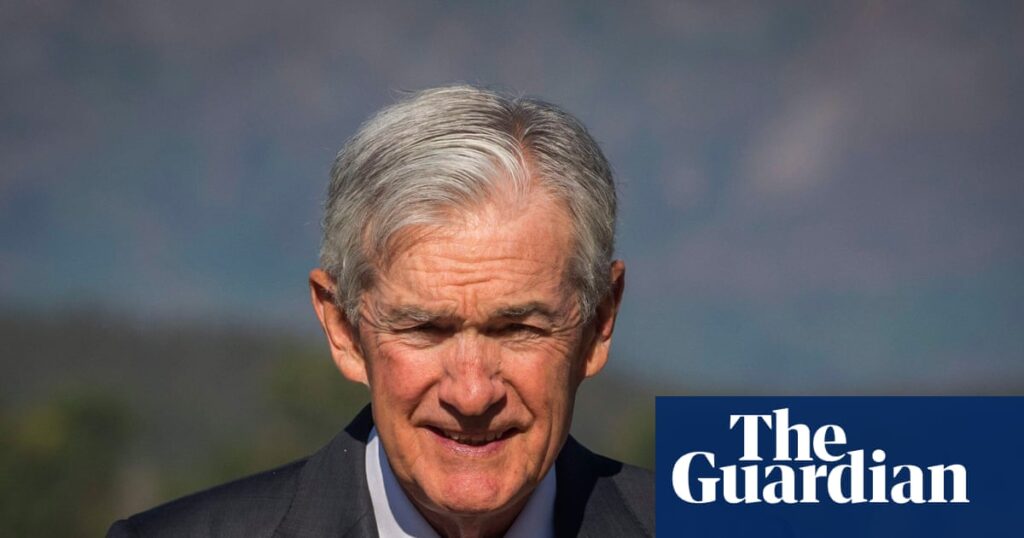

While Wall Street cheered the biggest headline from Fed chair Jerome Powell’s speech at the annual Jackson Hole symposium in Wyoming, Powell also delivered a reality check on where interest rates could settle in the the longer term.

“We cannot say for certain where rates will settle out over the longer run, but their neutral level may now be higher than during the 2010s,” said Powell.

In other words: even if the Fed does start cutting interest rates again this year, they may not fall back to their pre-pandemic levels. It’s a signal, despite the short-term optimism on potential rate cuts, that the Fed’s long-term outlook is more unstable.

“Markets might be ahead of their skis on how aggressive the Fed is going to be in reducing interest rates, because the neutral rate might be higher than some believe,” Ryan Sweet, an economist at Oxford Economics, said.

Higher rates means borrowing money for loans, such as mortgages, will be more expensive. The average 30-year fixed mortgage rate was just under 3% in 2021, when interest rates were near zero.

Now the average mortgage rate is closer to 6.7%. Paired with home prices at near-record highs, elevated mortgages mean many Americans will continue to struggle to purchase a home.

Although Trump has been pushing the Fed for months to decrease rates to 1%, claiming that Powell is “hurting the housing industry very badly”, it seems unlikely that rates will return to such a level any time soon.

The Fed is trying to achieve a Goldilocks balance. Rates that are too high risk unemployment, while rates that are too low could mean higher inflation. Policymakers are searching for a “neutral” level, where everything is just right.

Many economists believed the central bank was close to achieving this balance before Trump started his second term. In summer 2022, as inflation scaled its highest levels in a generation, the Fed started raising rates, at the risk of hurting the labor market, in an attempt to get inflation down to 2%.

Rates rose to about 5.3% in less than two years, but the jobs market remained strong. Unemployment was still at historically low even as inflation came down. Although some economists had feared rapidly increasing rates would throw the US economy into a recession, instead the Fed appeared to achieve what is known as a “soft landing”.

But things were thrown into a tailspin when Trump returned to office, armed with campaign promises to enact a full-blown trade war against the US’s key trading partners.

The president has long argued that tariffs would boost American manufacturing and set the stage for better trade deals. “Tariffs don’t cause inflation. They cause succession,” Trump declared back in January, acknowledging that there might be “some temporary, short-term disruption”.

But so far, success has been limited. Economists doubt the policies will generate a manufacturing renaissance, and Trump’s trade war has inspired new trade alliances that exclude the US.

All the while, US consumers are starting to see higher prices due to Trump’s tariffs.

At Jackson Hole on Friday, Powell said tariffs have started to push some prices up. In June and July, inflation was 2.7% – up 0.4 percentage points since April, when Trump first announced the bulk of his tariffs.

This is still only a modest increase in price growth, but the bulk of the White House’s highest tariffs only went into effect in early August. Fed policymakers are waiting to see whether Trump’s aggressive trade strategy will cause a one-time shift in price levels – or if the effects will continue.

The once strong labor market has grown sluggish. Though there are fewer job openings, there are also fewer people looking for jobs. Powell called it “a curious kind of balance” where “both the supply of and demand for workers” have slowed. He noted that the balance is unstable and could eventually tip over, prompting more layoffs and a rise in unemployment.

This instability in the labor market has made Fed officials more open to a rate cut. Powell pointed to a slacking in consumer spending and weaker gross domestic product (GDP), which suggests an overall slowdown in economic activity.

Although it set the stage for a rate cut as soon as next month, Powell’s speech was far from optimistic.

“In this environment, distinguishing cyclical developments from trends, or structural developments is difficult,” he said. “Monetary policy can work to stabilise cyclical fluctuations but can do little to alter structural changes.”

From Powell, who is typically diplomatic and reserved in his public statements, this seemed to be a careful warning: when executive policies destabilise the economy, the Fed can only do so much to limit the damage.