If the 264 million students enrolled in higher education around the globe were a country, it would be the fifth most populous in the world. Some 53% of its citizens would identify as women and most would be located in Asia. Residents would speak and study in hundreds of languages, but English would dominate.

The future of universities

This nation of learners would also be one of the fastest growing. Since 2000, the number of university students around the world has more than doubled, and the number that cross borders to learn has roughly tripled, to almost seven million. Aided by the Internet, conferences, shared curricula and collaborations, the world of higher education has become more tightly linked.

But the pattern of interconnected growth is beginning to unravel as wealthy Western nations become much less welcoming to foreign students. The administration of US President Donald Trump in particular has been targeting higher-education institutions and international students. Many of the latter are consequently looking elsewhere to earn their degrees, and those opportunities are growing, especially in some low- and middle-income countries. But expanding access to higher education has also raised concerns about the quality and value of that education.

Universities must move with the times: how six scholars tackle AI, mental health and more

These changing currents are particularly crucial for science, which relies on the infrastructure of universities to train its students, share ideas and do research. “The current global scientific system is facing unprecedented risks to the things that have made it robust,” says Chris Glass, a higher-education researcher at Boston College in Massachusetts.

Specialists caution that there isn’t a universal portrait that captures the state of higher education around the world. “There’s never a global story,” Glass says. But he and other scholars have worked to identify key trends in the demographics of this ‘country’ of higher education — and predict where it’s going.

Here, Nature examines some of these trends: the growth of higher education, especially in less-wealthy nations; the geopolitical forces created by and shaping higher education; and how all this affects who gets to learn and what they are taught.

Who goes to university?

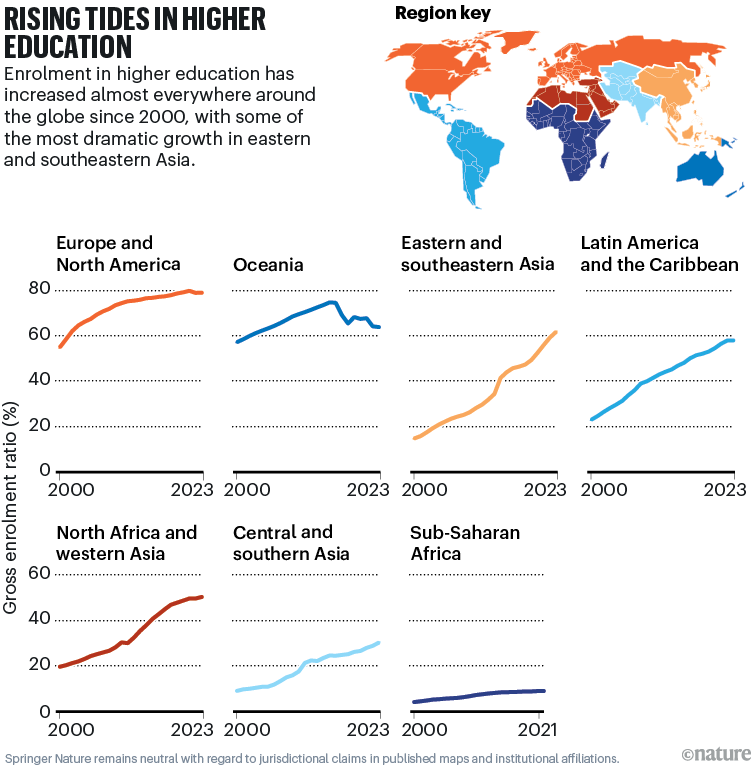

The overarching trend in higher education over the past half century has been an explosive growth in student numbers. Higher-education researchers typically track this growth by comparing the number of enrolled students in a country with its population of student-aged people, a measure called gross enrolment ratio (GER). (This ratio can even be higher than 100% because people outside this age range can attend universities.)

For countries in Western Europe and North America, participation in higher education is now the norm (see ‘Rising tides in higher education’). The higher-education GER in these regions increased from 61% in 2000 to 80% in 2024. In the past few years, however, this group has been surpassed by Central Europe, who leapt from an average GER of 42% to 87% in that same time span. The massive increase came mostly from an explosion of private education after the collapse of the Soviet Union.

Source: UNESCO

Other regions of the world are beginning to catch up: between 2000 and 2023, eastern and southeastern Asia’s GER went from 15% to 62% and Latin America and the Caribbean’s went from 23% to 58%. Many countries are making explicit efforts to expand their GER. India, which had a GER of 28% in 2021–22, has set a target of reaching 50% by 2035. The global average, which was 19% in 2000, has shot up to 44% in 2024.

Some regions are still struggling, however. Sub-Saharan Africa had a GER of 9% as of 2021, up from 4% in 2000. It is also the only region in which women are still under-represented in higher education; there are roughly 76 women for every 100 men. The primary obstacle is funding, says James Jowi, director of the African Network for Internationalization of Education, a non-profit organization based in Eldoret, Kenya. “Most young people can’t afford a college tuition fee,” Jowi says.

Universities under fire must harness more of the financial value they create

Increasing access is not without concerns, however, says Laura Rumbley, the director for knowledge development and research at the European Association for International Education in Amsterdam. As peoples’ level of education rises, so too do the qualifications necessary for good jobs. In regions with extremely high enrolment, higher-education degrees, including master’s and PhDs, become more necessary and less valuable, she says. “We want to avoid higher education becoming a dead end for individuals and for societies.” Higher education should open doors, not close them, she says.

Where do students go to learn?

As the number of students and institutions has expanded, higher education has become more globally linked, but the shape and nature of those connections is changing.

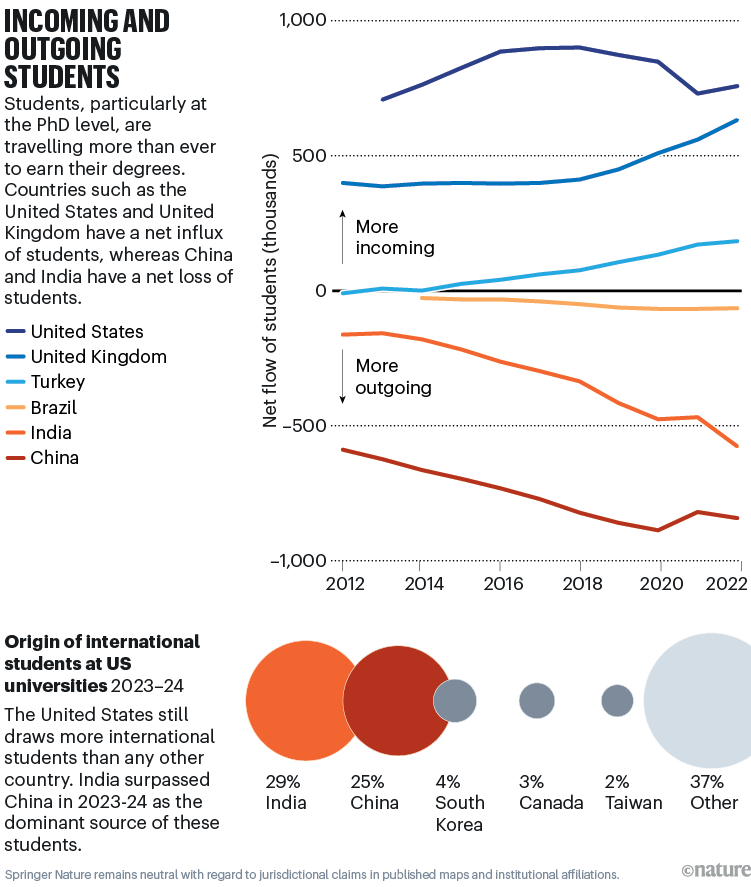

Researchers describe these connections as internationalization: how globalization takes place at university. The clearest and easiest way to see this is in student mobility, Rumbley says. In 2000, 2.1 million students crossed borders to learn; today, 6.9 million do, about 2.6% of all students. In some regions, such as the European Union, international travel for education is much more common: about 9% of its students go abroad, often to other countries in the EU.

Much of the mobility comes from postgraduate students seeking more specialized education that is not necessarily available locally. And the flow of students is generally towards wealthy nations that have invested heavily in public education. For example, the United States has about 20 million students in higher education, 1.1 million of whom come from other countries. Meanwhile, India has 43 million students but only 46,000 are international (See ‘Incoming and outgoing students’).

Source: UNESCO

However, specialists say there might be a slowing down of this typical movement because of two factors: an increase in the availability of education in low- and middle-income countries and a decline in access to universities in many wealthy nations. The United Kingdom, Canada and Australia have all imposed immigration restrictions that have begun to chip away at undergraduate and postgraduate enrolment from abroad. And anti-immigration policies in the United States are increasing. The Trump administration has revoked more than 1,400 visas, restricted travel from 19 countries and proposed rules to limit visas for PhD candidates to 4 years, despite US programmes often taking longer than that to complete. NAFSA: Association of International Educators, a non-profit organization based in Washington DC, projects that there will be roughly 30–40% fewer international students entering the United States by 2025–26 than for the previous academic year, at a cost of about US$7 billion in revenue and 60,000 jobs.

Before the start of the twenty-first century, the United States had a “diversified portfolio” of international students, Glass says, from many countries. Over the past two decades, however, China and India have come to dominate, going from about one-third to more than half of the number of students in the US international study body. This rise has been fuelled by demand from increasingly wealthy middle classes in those countries and opportunities provided by US universities hungry for more funds, Glass says.

Students in China and India now have other options. Although the United States, the United Kingdom, Canada and Australia are still top destinations for international students, countries such as the Netherlands and South Korea are increasingly popular. And China is working to attract more foreign students. In 2000, the United States was host to about 26% of all international students; today that number is about 16%.

How universities came to be — and why they are in trouble now

Another way that universities have tried to tap into increasing global demand is through satellite campuses: extensions of highly visible institutions in foreign cities, such as New York University’s venture in Shanghai, China. These institutions have created opportunities for international education without the need to cross borders. In 2023–24, the United Kingdom hosted about 732,000 international students domestically, but it educated roughly 621,000 students abroad, studying at foreign extensions of UK universities. “That might be a trend which will be increasing, because then you have students that can say, ‘Well, I don’t have to travel abroad, but I still can have a foreign degree’,” says Hans de Wit, a higher-education researcher at Boston College. This transnational approach can avoid troublesome visa issues, but raises difficult questions, he says, such as whether it is really the same quality education?

For many it is not. “If I were a student, I would be studying in Bristol University in the UK, not in Delhi,” says Saumen Chattopadhyay, an economist who studies higher education at Jawaharlal Nehru University in New Delhi. Studying abroad provides more opportunities to emigrate and gain access to international contacts.

Although opportunities to go abroad can help individuals, they can drain talent and money from less-wealthy countries. “It has been considered for a long time a threat to the human capital development from African countries,” Jowi says. He is working to develop intra-Africa mobility and reduce brain drain by building local centres of excellence at universities in southern and eastern African countries.