October 30, 2025

3 min read

Glowing Sperm Reveals How Female Mosquitos Control Sex

Female Aedes mosquitoes signal that copulation can proceed by subtly extending their genitalia

Sex between Aedes aegypti mosquitoes lasts about 14 seconds.

Jacopo Razzauti/The Rockefeller University

Female mosquitoes that transmit dengue and other diseases are actually in charge during sex, according to a study that challenges the long-held view that they are passive participants.

Leslie Vosshall, a neurobiologist at the Rockefeller University in New York City, and her team were intrigued by the observation that male mosquitoes of the Aedes genus seem to pursue females constantly, yet females typically mate only once in their lifetimes. “The question was: how are the females able to say no?” Vosshall says.

Using fluorescent sperm and some careful camera work, the researchers showed for the first time that, when a male Aedes mosquito initiates contact, the female extends the tip of her genitals by a fraction of a millimetre — roughly the thickness of a human fingernail. If the female does not give this subtle, but crucial, signal, the male’s efforts fail, and copulation does not occur.

On supporting science journalism

If you’re enjoying this article, consider supporting our award-winning journalism by subscribing. By purchasing a subscription you are helping to ensure the future of impactful stories about the discoveries and ideas shaping our world today.

Mosquito sex lasts only a few seconds, and usually occurs in mid-air. These factors, combined with the minute size of the genitals, have made it difficult to study exactly what’s going on, Vosshall says, adding that the scientists who previously studied mosquito breeding probably just shrugged and said, “Yeah, the male is in charge.” Her team’s findings, which could have implications for controlling disease-carrying mosquitoes, were published today in the journal Current Biology.

Fluorescent sperm

To study the intricate mating process of Aedes aegypti — the main species of mosquito that transmits dengue — Vosshall and colleagues first engineered transgenic males that produce either green or red fluorescent sperm. Then they put some of each type into a cage with females of the same species for seven days. When the females were dissected at the end of that period, more than 90% of them had sperm of only one colour stored in their bodies, supporting the idea that they mate only once in their lifetime.

In a second set of experiments, the team filmed the mating process using an elaborate set-up. The researchers glued a female mosquito to a metal pin, so that she could move her wings and legs but not fly away, like a trapeze artist in a rigid tether. They then introduced free-flying males into the cage, and recorded the interactions between the male and female genitals at high resolution.

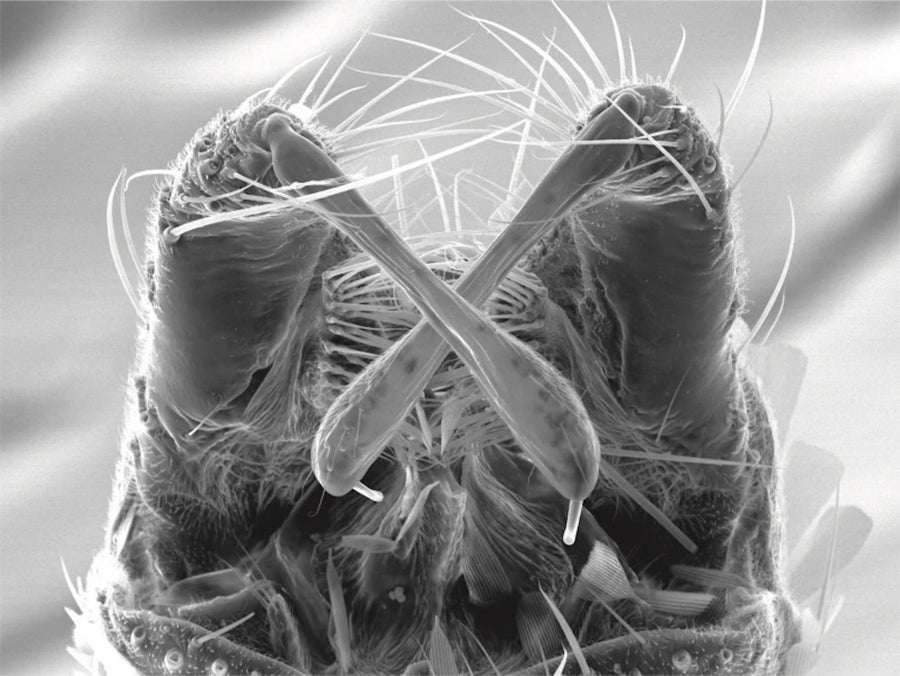

Male Aedes mosquitoes use drumstick-like genital structures called gonostyli (shown here, crossed) to tap on the genitalia of females when initiating sex.

H. Amalia Pasolli, Anurag Sharma/The Rockefeller University

Leah Houri-Zeevi, a researcher in Vosshall’s lab, spent hundreds of hours looking at the videos, frame by frame. She noticed that when a male is trying to copulate, he doesn’t simply extend his sex organ — the equivalent of a penis — towards the female. Instead, he first taps the female genitalia with drumstick-like structures called gonostyli. In response to the tapping, a virgin female might elongate the tip of her genitalia, to enable copulation. Houri-Zeevi noticed that non-virgin females, however, typically kept their genitals retracted, blocking further mating attempts.

“It’s really interesting, because there seems to be a code of receptivity,” says Nildimar Honório, an entomologist at the Oswaldo Cruz Institute in Rio de Janeiro, Brazil.

Breaking the code

Vosshall and colleagues say that this is a lock-and-key mechanism, in which the gonostyli serve as the key to open the female lock. They identified the same mechanism in Aedes albopictus mosquitoes, a species that evolutionarily split from A. aegypti 35 million years ago.

However, they also noticed that A. albopictus males can bypass the female-control mechanism when they mate with A. aegypti females. “Aedes albopictus takes its enormous gonostyli and is basically able to open up the genital parts of Aedes aegypti females and copulate with them,” Vosshall says. This interspecies sex doesn’t generate viable offspring, and it causes the A. aegypti females to reject further advances from males of their own species. “If you do that to enough females, then the species becomes extinct,” she says.

Understanding these interactions could help to explain real-world phenomena, with potential implications for public health. Whereas A. aegypti, native to Africa, first arrived in parts of the Americas and Europe hundreds of years ago, A. albopictus — which can also transmit dengue and chikungunya — was introduced to these regions just a few decades ago. “There are now areas where both species coexist, and what happens is that albopictus is outcompeting aegypti,” says Claudio Lazzari, an entomologist at the University of Tours in France. That’s because A. albopictus males are mating with A. aegypti females and, in practice, sterilizing them.

This article is reproduced with permission and was first published on October 28, 2025.

It’s Time to Stand Up for Science

If you enjoyed this article, I’d like to ask for your support. Scientific American has served as an advocate for science and industry for 180 years, and right now may be the most critical moment in that two-century history.

I’ve been a Scientific American subscriber since I was 12 years old, and it helped shape the way I look at the world. SciAm always educates and delights me, and inspires a sense of awe for our vast, beautiful universe. I hope it does that for you, too.

If you subscribe to Scientific American, you help ensure that our coverage is centered on meaningful research and discovery; that we have the resources to report on the decisions that threaten labs across the U.S.; and that we support both budding and working scientists at a time when the value of science itself too often goes unrecognized.

In return, you get essential news, captivating podcasts, brilliant infographics, can’t-miss newsletters, must-watch videos, challenging games, and the science world’s best writing and reporting. You can even gift someone a subscription.

There has never been a more important time for us to stand up and show why science matters. I hope you’ll support us in that mission.