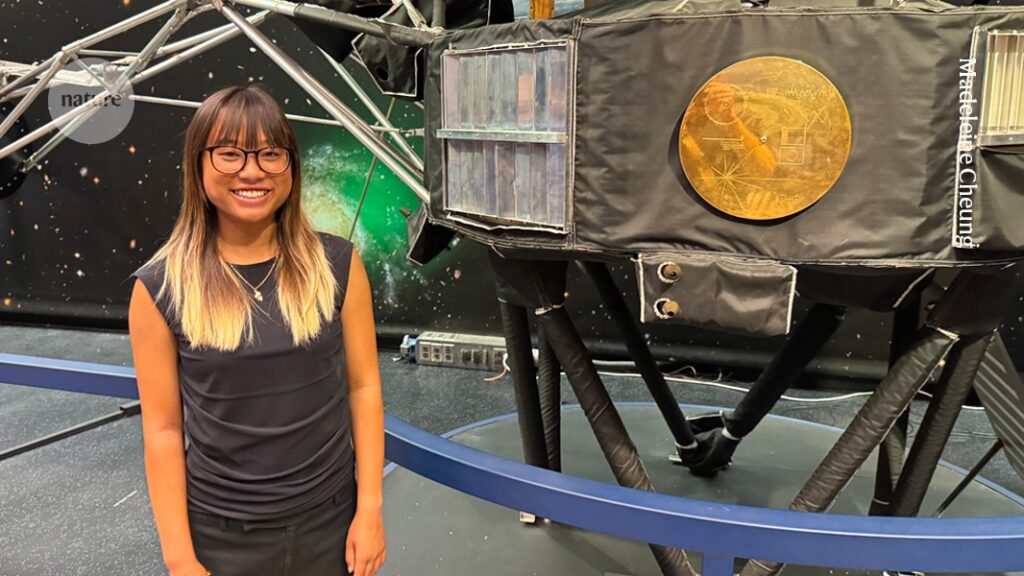

Madeleine Cheung in front of a model of the Voyager spacecraft during one of her visits to NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory.Credit: Madeleine Cheung

M.C.: In October 2023, two months into an America and World Relations course at my secondary school in Los Angeles, California, our teacher told us to find a mentor working in a field in which we were interested in pursuing a career.

I wanted mine to be a scientist who could tell me about their day-to-day role and how they use their work to further humanity’s knowledge.

But I wasn’t sure how to find one. My teacher suggested using my existing network, such as friends’ parents. But a friend encouraged me to approach C.M., a carbon-cycle and ecosystems researcher, when he spoke to our class about his work at NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory (JPL), based at the California Institute of Technology (Caltech) in Pasadena. This was my first interaction with someone in environmental science, a field I hope to work in. He agreed to be my mentor.

Our first virtual meeting was in May 2024, and was followed by a couple more over the summer break. We talked about how a scientist finds and publishes knowledge, which introduced me to various types of journal. We also made a plan for the upcoming school year (during which we met virtually for 30 minutes each week), focusing on the research areas I was interested in learning more about and, hopefully, contributing to.

Getting started

During our weekly meetings, we talked about C.M.’s research on Arctic tipping points (an abrupt or irreversible change into a qualitatively different state), and I gradually started to play a more active part in the sessions by finding papers and summarizing their findings. This February, I visited C.M. at JPL, where I met his colleagues, who shared their career journeys with me.

At the end of my two-year America and World Relations course, I gave a presentation reflecting on my experience with C.M., including how we met, what we did and what I learnt. His mentorship provided invaluable exposure to careers in science and gave me a real understanding of research. Tasks I completed, such as literature reviews, could form part of C.M.’s research paper on Arctic tipping points, and that has given me confidence in my ability to contribute to scientific work.

The mentorship also challenged some of my misconceptions. I had assumed that, to go into environmental science, I would need to focus on this for my bachelor’s degree. However, C.M.’s degree is in chemistry and history. This taught me that you can take various routes into science, and that your undergraduate years should be a time of exploration.

I learnt that science is, first and foremost, one big group project (often a global collaboration, in fact), rather than a lonely pursuit full of technical jargon and rigid methods, which is how some of my peers perceive it.

The mentorship also introduced me to resources such as Google Scholar and the US National Snow and Ice Data Center, showing me how open science can provide free, accessible knowledge. I realized that C.M. uses some of the same tools that I used at school, such as group to-do lists and presentations to summarize work for others. As a result, science feels more attainable, and less like a far-off fantasy restricted to the most brilliant minds.

Mixing it up

My mentoring experience with C.M. wasn’t my only exposure to careers in science during my time at school; I also took part in the Summer High School Intensive Next-Generation Engineering program at the University of Southern California in Los Angeles. As part of environmental engineer Burçin Becerik-Gerber’s research group, I worked on a project that aimed to understand how energy dashboards in residential homes can motivate people to reduce their energy usage.

The other two school students in that group were male, as were the two PhD students we worked with. Meanwhile, at school, in my combined physics and chemistry class, I was one of only two female students in a class of seven, with a male teacher.

These experiences reminded me that being a young woman in science, technology, engineering and mathematics (STEM) can seem daunting, despite the strides society has made to embrace gender equality in the STEM fields.

Overall, I now feel more comfortable about stepping into a male-dominated field. I hope to use my experience to relate to and motivate girls and young women to pursue STEM-related careers.

Here are three tips I would give to any secondary-school student looking to get immersed in the world of science and research.

First, keeping an open mind allows you to step into situations and experiences that you might not have thought possible. Throughout the mentorship, I carried out tasks despite having doubts about my ability. Although it is important to have some goals in mind, having too many expectations while still at school can prevent you from reaching your potential and truly getting the most out of the journey.

Mentoring resources

Second, asking about the possibility of a mentorship in person, rather than digitally, such as over e-mail, makes the relationship more personable from the beginning and gives you a higher chance of receiving a follow-up. Before meeting C.M., I had reached out to three people online, but found that cold e-mailing was ineffective.

Last, I found that having the support of your school, and specifically that of a teacher who can vouch for you, is indispensable in ensuring that the process goes as smoothly as possible. If other adults are already aware of your goal, it can open the door to more connections, and reassure the person you reach out to.

Moving on

The world I was born into has changed from simply questioning climate change and the reasons for it to joining together to mitigate its effects. I have grown into a young woman confident in following a path of environmental advocacy through STEM. By 2030, I will have finished the undergraduate degree that I started last month, and hope to have been witness to a crucial climatic milestone: the reduction of greenhouse-gas emissions by 45% to keep the global temperature increase under 1.5 °C above pre-industrial temperatures.

But immersing myself in professional science while still at school has convinced me that I need not be just a witness; with the right tools, I feel ready to use my voice to be a positive contributor to a more sustainable world.

Secondary-school student Madeleine Cheung visited environmental scientist David Miller at NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory in California.Credit: Madeleine Cheung

C.M.: My daughter attends the International School of Los Angeles, and once or twice a year I go there to talk to the science classes. I met M.C. during one of these visits.