In May and June, Nature surveyed 3,785 PhD candidates from around the globe, exploring everything from supervision practices to workplace concerns. The results, published today, offer a window into how today’s doctoral researchers are adapting to the rapidly changing circumstances in science, technology, engineering and mathematics. It’s a mixed bag: candidates report feeling happier overall, but serious problems persist.

Collection: Career resources for PhD students

The good news? PhD satisfaction levels have bounced back from their pandemic lows (Nature’s most-recent global PhD careers survey took place in 2022). The sobering reality? Nearly half of respondents worldwide say that they still face discrimination or harassment, and many report seeing their supervisors for less than an hour each week. Beyond these challenges, doctoral candidates consistently cite poor compensation and inadequate career guidance as major sources of dissatisfaction.

As new technologies transform how doctoral students work, one thing hasn’t changed: academia continues to hold the crown as their preferred career destination.

Here’s what the data reveal about the state of the doctorate in 2025.

Post-COVID recovery

Some 75% of the PhD candidates surveyed feel satisfied with their doctoral studies. This is a bounce back from 62% in 2022, and a rebound to pre-COVID levels: satisfaction levels were 71% in Nature’s 2019 survey and 78% in 2017.

The dip in satisfaction during the pandemic makes sense to Pil Maria Saugmann, outgoing president of Eurodoc, an organization based in Brussels that represents early-career researchers in Europe. “I had a year when all my supervision was online, all interactions with my group were online,” says the Danish researcher, who finished her theoretical-physics PhD at Stockholm University in 2022. “I’m not surprised that the numbers have gone up, because it reflects that we are in a more normal state where there is a collegial environment.”

Some 78% of doctoral candidates in the survey feel most satisfied with the independence and flexibility that their PhD gives them (see ‘How PhD students rate their experiences’). “No other job has the independence, constant challenges, flexibility and stimulating environment that a PhD offers,” says Miguel González Martín, a mechanobiology PhD candidate at the Institute for Bioengineering of Catalonia in Barcelona, Spain. He says that his PhD allows him to keep learning new things at a high pace, and he feels privileged that his job gives him the opportunity to help solve global problems.

Roughly 73% of respondents are satisfied with their relationship with their supervisor and 66% report satisfaction with the guidance they receive about their research. “My supervisor gives me the freedom to explore my research ideas while providing constructive feedback whenever I need it. This balance helps me grow as an independent researcher,” says a fourth-year PhD student in Iran who took the survey.

Fewer respondents are satisfied with their compensation and benefits: only 47%. Women are more dissatisfied with their PhDs than men are — 19% feel moderately, very or extremely dissatisfied, compared with 15% of men. Those who identify as members of ethnic minority groups show a similar trend (20%, compared with 17%). Saugmann says that there are certain survey findings that point to other areas of dissatisfaction, too, such as high levels of harassment and discrimination, which are higher than in some other employment sectors, she says.

How many PhDs does the world need? Doctoral graduates vastly outnumber jobs in academia

Spending long hours on a PhD — 60 or more a week — also significantly correlates with lower satisfaction. This probably contributes to only 60% of PhD students in China reporting being satisfied, says Yanbo Wang, a science-policy researcher at the University of Hong Kong. PhD researchers there often work seven days a week, he says. And because many enrol for PhDs not because they want to do research, but to gain an advantage in China’s cut-throat labour market, they might lack the passion to makes all that hard work feel worthwhile. Wang says. “That mismatch is a huge part of the problem.”

About 55% of respondents say that their PhD experience matches what they expected, whereas 34% feel their expectations aren’t being met. That dissatisfaction rises to 39% in India, where Shubha Tole, dean of graduate studies at the Tata Institute of Fundamental Research in Mumbai, says that a boom in the number of undergraduate students has increased competition for summer research placements and internships. As a result, most incoming graduate students lack such experiences and know little about how to conduct research and the research culture, she says.

Mo money, mo politics

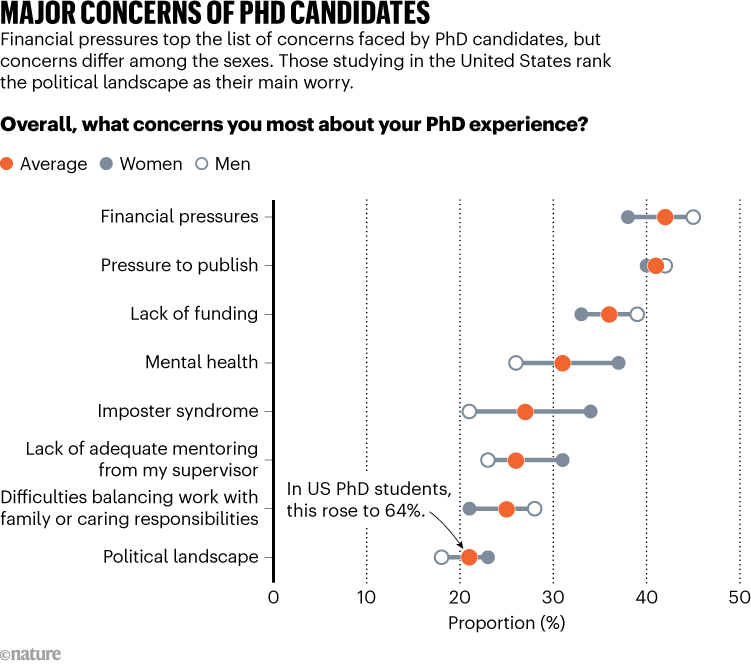

When asked about broad concerns, the two most common were financial pressures (42% chose this option) and the need to get published (41%; see ‘Major concerns of PhD candidates’). “I wish we got paid a living wage. It’s hard to focus on research when I’m worried about my next meal,” said a female second-year PhD candidate in the United States.

Mental health is a concern for 31% of the global sample, and 25% worry about balancing their studies with family and caring responsibilities.

Asked about specific concerns, rising living costs worry 86% of the respondents, up from 85% in 2022, and 55% agree that increases in inflation will negatively affect their decisions to continue their studies. These financial concerns are “alarming”, says Mohammed Shaaban, a recent PhD graduate from the Francis Crick Institute and Imperial College London. “If this continues, we will see more students either quitting their programmes early or opting out of academic careers.”

These nations are wooing PhD students amid US funding uncertainties

The political landscape is a key concern for just 21% of respondents. However, this jumps to 64% in respondents in the United States — their biggest concern by far. Teddy Warner, president of the graduate-student council at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology in Cambridge, traces this to upheavals in the US science system under US President Donald Trump’s administration since January. “I’ve seen how things were before and after Trump’s inauguration, and mostly this year’s been much more chaotic and uncertain,” Warner says.

Funding cuts have been a major source of anxiety for US graduate students, especially those early in their programmes, who worry that they might not be able to start. Crackdowns on immigration have also taken a toll, Warner says, and “there is an overall atmosphere of fear”, with some international students avoiding international travel, afraid that they might be stopped at the border.

The political turmoil in the United States spills beyond PhD candidates there, says Wang. “Given what’s going on, more and more Chinese researchers are coming back to China,” cranking up competition for post-PhD positions at home, he says.

AI’s (wary) adopters

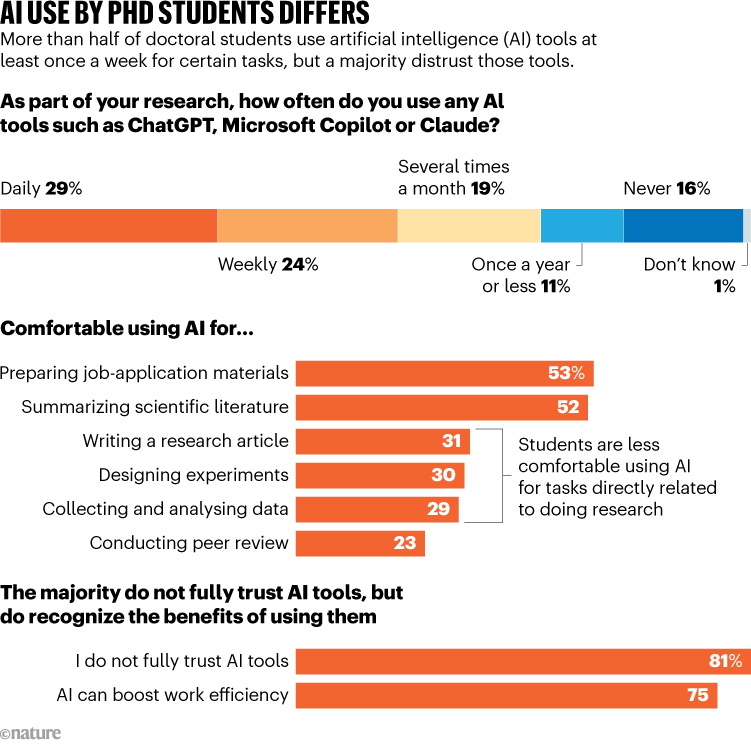

This year’s survey is the first to ask PhD candidates about their views on and use of artificial intelligence (AI) tools. Some 53% say that they use AI tools at least weekly, in service of their PhD studies, whereas merely 16% have never used them (see ‘AI use by PhD students differs’). Roughly 75% they think that AI can help them work more efficiently and 71% think that it is acceptable for them to use AI as part of their PhDs.

Most PhD candidates feel comfortable with using AI for tasks such as preparing job applications or summarizing or tracking the scientific literature. They feel less comfortable using AI for near-research tasks such as collecting and analysing data, designing experiments, writing articles and peer reviewing. Some 81% ‘don’t fully trust’ AI. Meanwhile, 82% are concerned about the quality and integrity of AI outputs, and 65% worry that AI weakens their critical thinking and research and writing skills; 64% are concerned about the reproducibility of AI outputs.

The total sample is split on whether AI will replace core skills (43% agree and 40% disagree) and roles (42% agree and 39% disagree). Survey-takers warn about the dangers of AI dependency. “You become too overly reliant on AI tools and it ends up affecting critical thinking and self-confidence,” writes a male PhD candidate studying in India. A fourth-year female student, also in India, writes that she feels ChatGPT “spoiled the thinking power of my brain”.

Some 64% say they want more guidance from their institutions about how best to use AI in their work. Shaaban, who was encouraged to use AI responsibly during his PhD in London, agrees: “This is a revolution. We need to put a lot of effort into training people how to use it responsibly, not just leave it up to trial and error.”

Harassment and prejudice abound

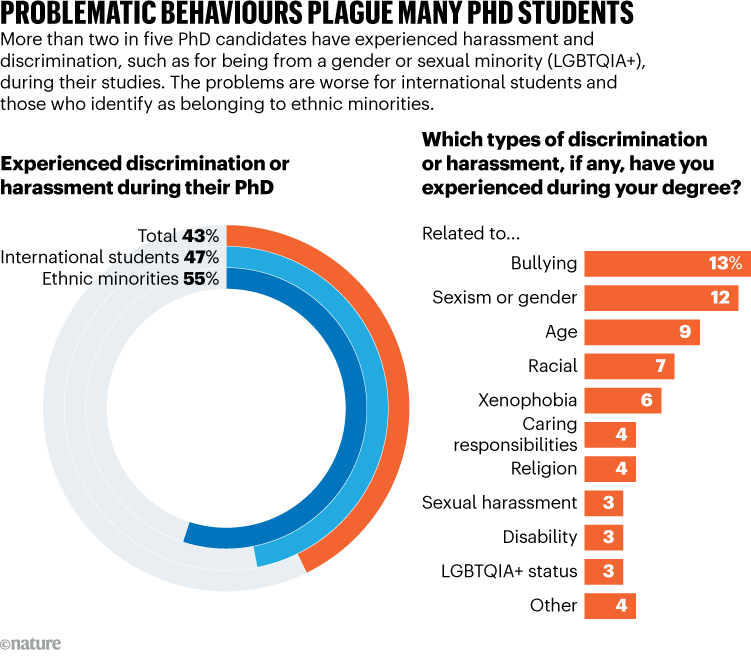

A notable 43% of respondents say that they have experienced discrimination or harassment as part of their studies, with the most common types being bullying and sexism (see ‘Problematic behaviours plague many PhD students’). This is an increase from the 20% in Nature’s 2022 PhD survey, although there, a separate question dealt with bullying, which 18% said they had experienced. This year’s survey gave respondents more-specific types of discrimination and harassment to choose from, including those based on religion, sexual orientation and disability, which makes comparisons with previous surveys difficult. In any case, with more than two in five PhD candidates in 2025 reporting experiencing discrimination and harassment, problematic workplace cultures persist, with direct effects on well-being.

“If you ask whether there is a mental-health crisis in doctoral training, the answer is yes,” says Saugmann. She says that Nature’s findings echo those of other surveys looking at mental health in European universities.

These harassment experiences shoot up to 47% in international students and 55% among those who identify as belonging to ethnic minorities. “It’s deeply concerning that half of the international students experience discrimination,” says Shaaban, who experienced discrimination related to his Egyptian nationality, both in the United States, where he studied from 2018 to 2020, and during his PhD in the United Kingdom. In the United Kingdom, this came mainly from broader society and not his workplace, he says. Nevertheless, he says, “it makes you feel unappreciated, like you don’t belong”.