The only major difference between the sun and the stars we see at night is that the sun happens to be close to us—which is advantageous, assuming you enjoy being alive.

Astronomers enjoy this as well but have another reason for rejoicing in the sun’s proximity: this allows us to see it as a disk. The sun is, of course, three-dimensional. But from a distance, we see it as a filled circle in the sky, and that means we can study its surface in some detail, revealing its sunspots, faculae, granules and other amazing features.

The stars in the night sky are a bit farther away; the nearest one to us, Proxima Centauri, is roughly 280,000 times more distant than the sun! This makes it appear correspondingly smaller through a telescope—infinitesimally smaller, in fact, appearing as only a point of light. When an object appears this way, we say it’s unresolved; when it’s apparently big enough to exhibit an actual shape, then it’s resolved.

On supporting science journalism

If you’re enjoying this article, consider supporting our award-winning journalism by subscribing. By purchasing a subscription you are helping to ensure the future of impactful stories about the discoveries and ideas shaping our world today.

Is it possible to see any other stars the same way we see our sun, resolved in all (or at least some) of their glory?

Well, technically, yes. Practically speaking, though, it’s hard.

A telescope’s visual acuity depends on the size of its light-gathering aperture, which is usually a mirror or a lens. If we crunch the numbers, there are quite a few stars that appear large enough in the sky to be resolved by our biggest telescopes. But there’s still a problem: our turbulent atmosphere smears out details of astronomical objects.

This sets a limit of sorts on the smallest details you can see for objects on the sky. But clever techniques can work around this limitation, including adaptive optics, which rapidly reshapes a mirror in the telescope to counter the motion of overlying air. Another is speckle imaging, which uses sequences of extremely short exposures to freeze out that same motion. In the 1970s astronomers used a variation on this technique to get sharp images of several nearby large stars, including Antares in Scorpius and everyone’s favorite incipient supernova, Betelgeuse in Orion. Mind you, while these are large stars physically, they’re so far away they appear small, less than 0.00002 degree in width, about the same size a U.S. quarter would appear from a distance of 100 kilometers. The sun is half a degree in size, for comparison—more than 30,000 times larger.

As clever as these techniques are, they still face the more fundamental obstacle of aperture size defining a telescope’s resolution. Building even bigger ground-based telescopes would help but offers diminishing returns: at a certain size—around what we already have today—the task becomes prohibitively difficult and expensive.

But there’s another technique that can circumvent even this limitation! It’s called interferometry, and it depends on the fact that light is a wave.

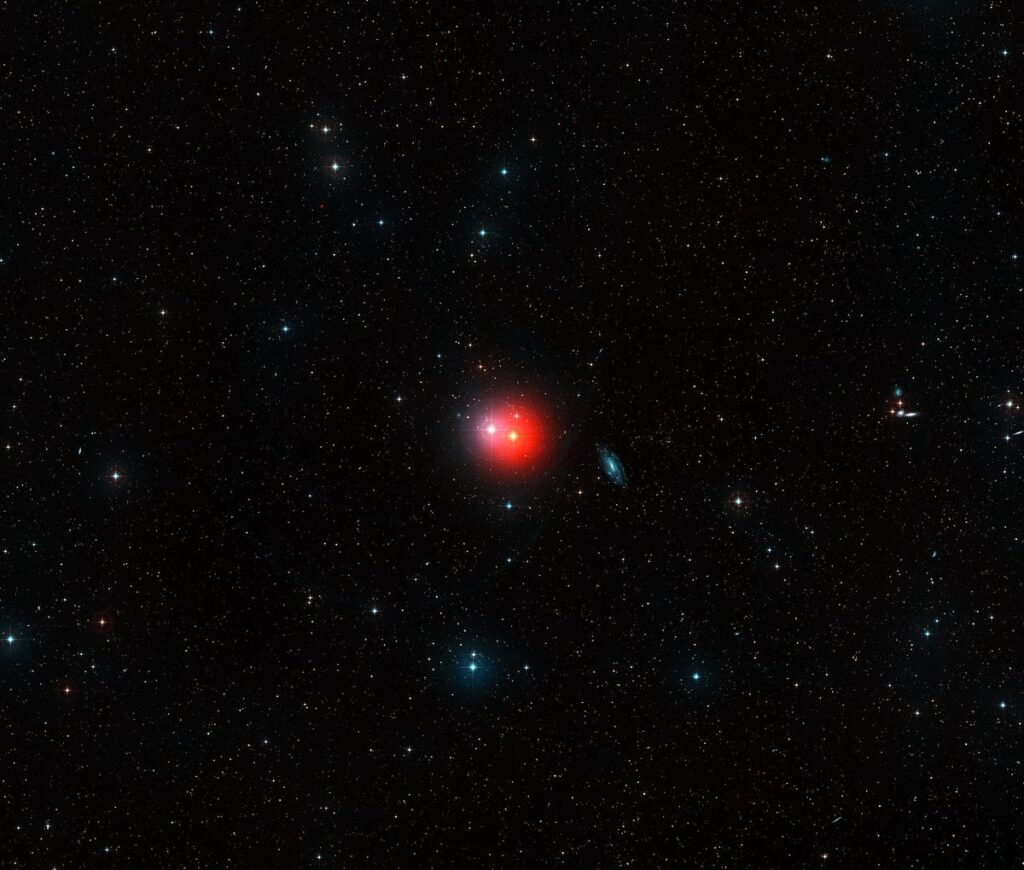

An interferometric view of the red giant star π1 Gruis, as seen by the PIONIER instrument on ESO’s Very Large Telescope. The resolved image reveals convective cells that make up the surface of this huge star. Each cell covers more than a quarter of the star’s diameter and measures about 120 million kilometers across.

Technically light is an oscillation of electric and magnetic fields, but it still acts, in most circumstances, exactly like a wave. A beam of light has crests and troughs, and when two beams pass through each other, they can create interference. Crests and troughs add together, sometimes making higher crests and lower troughs or sometimes canceling each other out.

You’re probably already familiar with this phenomenon, which works for other types of waves as well. If you sit in a bathtub full of water and scooch back and forth in a rhythmic way, you create waves that move up and down the length of the tub. When the crests of two waves pass each other, they can get so tall they splash water out of the tub. Congratulations! You’ve done complex physics at bath time.

Light from a star can behave this way, too. Typically the interference isn’t as simple as interacting pairs of crests or troughs; a star’s light has multiple wavelengths, and the resulting pattern it forms in any telescope is quite complex. But that structure, called the interference or fringe pattern, encodes information about its stellar source, including size, shape and brightness distribution (that is, which parts of it are brighter or dimmer than others).

Here’s the very clever part: if you have two telescopes separated by some distance, the light from both can be sent to a device that adds them together to create interference patterns that can be analyzed, decoded and then used to create an image of the object that maps its details. Critically, though, the resolution of these telescopes is defined by their separation, not their size. Two modest telescopes 100 meters apart could, in principle, see as much detail as a telescope as wide as a football field!

This technique is called interferometry. Astronomers demonstrated it with radio telescopes in the 1940s and 1950s, and it’s now routine in radio observations. Interferometry becomes more difficult, however, as the wavelength of light shortens. The “optical” wavelengths of visible light, for instance, are far shorter than radio, so combining them is much more complicated. Still, over the years, optical interferometry has been developed with great success.

One of the largest telescopes in the world, the Very Large Telescope (VLT), consists of four 8.2-meter telescopes (as well as four smaller telescopes) that cover a distance of more than 100 meters, giving them phenomenal resolution. But even that’s not the biggest: the Center for High Angular Resolution Astronomy (CHARA) array has six one-meter telescopes separated by as much as 330 meters. CHARA has a resolution better than a millionth of a degree, more than enough to see features on a decent sampling of stars. In fact, most of the resolved images we have of stars are from CHARA.

Superhigh-resolution images of stars have revealed many surprising—and frankly weird—structures. The VLT peered at the red giant π1 Gruis and found that it has huge bubbles of hot gas rising from its interior. CHARA looked at the bright star Altair and saw that it’s distinctly egg-shaped as a result of its very rapid rotation. CHARA observations of the massive hypergiant RW Cephei showed its shape to be irregular and changing, indicating that it blew out a huge, starlight-smothering dust cloud in 2022, like Betelgeuse did in 2019.

As for Betelgeuse itself, it has been at the focus of interferometers many times. Its size has changed over the years, and the surface has been found to be complex, roiled by huge bubbles of hot gas like those of π1 Gruis. Massive red supergiants such as Betelgeuse create much of the dust we see scattered throughout the galaxy, but the mechanism isn’t well understood. Interferometric observations can help astronomers investigate how this happens.

The resolution of optical interferometry is limited only by our engineering and the speed by which computers can process the data. It’s anyone’s guess how large such a virtual telescope can get—in fact, the Event Horizon Telescope, which linked radio telescopes around the globe to make images of the magnetic fields around the Milky Way’s central black hole, is effectively as big as Earth! As our technology advances and improves, we may yet see the faces of far more stars and learn from them as we have from our own sun.