J

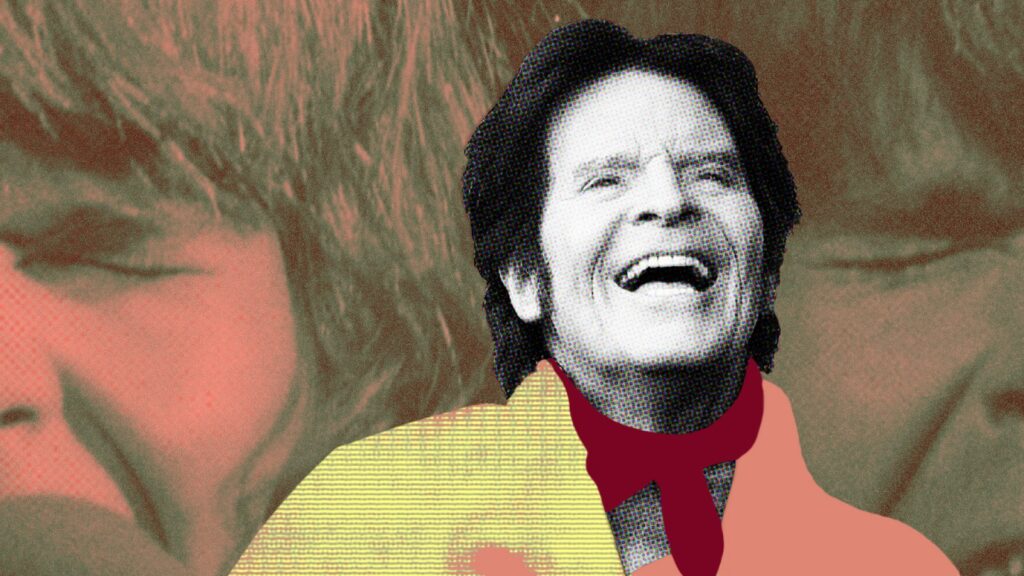

ohn Fogerty rerecorded some of the best-known songs by his long-gone band for his new album, Legacy: The Creedence Clearwater Revival Years, a Taylor Swiftian move that’s best understood as the culmination of his decades-long journey toward reclaiming those hits. Fogerty spent years in a series of ugly legal battles with the late executive Saul Zaentz, who owned Creedence’s catalog; most infamously, Zaentz once unsuccessfully sued him for purportedly plagiarizing his own composition, “Run Through the Jungle,” with 1984’s “Old Man Down the Road.”

Two years ago, Fogerty got the publishing rights back to his Creedence songs, a triumph he saw as a liberation after decades as a “prisoner of war.” In an interview for Rolling Stone’s Last Word column — which also appears as a new episode of our Rolling Stone Music Now podcast — Fogerty looks back at his time in Creedence, discusses his early influences, shares thoughts on mortality and legacy, and much more. (To hear Fogerty’s entire interview on Rolling Stone Music Now, go here for the podcast provider of your choice, listen on Apple Podcasts or Spotify, or just press play above.)

In the midst of those conflicts, Fogerty felt so alienated from his past that he refused to even play the songs onstage. (It was Bob Dylan who got him past his recalcitrance, pointing that people would think “Proud Mary” was a Tina Turner song if Fogerty didn’t sing it.)

You got the publishing rights back to Creedence Clearwater Revival’s songs two years ago. It’s been a long journey.

I wrote the songs and I have been fiercely proud of my accomplishment all my life, even though so many things in a legal sense or financial sense were turned against me. And even in the awareness sense in the public, you might say. I read a review about myself somewhere in Europe and the guy said … that I’m not a household name. And in many aspects that’s true. Which has been a bit frustrating to not have that awareness, because I named myself Creedence Clearwater Revival.

I knew the songs were good. I’m very proud of that. When all this stuff went bad after Creedence breaking up and all that, I still knew. And also I felt really crummy. One of the things I talk about now is getting my Rickenbacker back. It’s very symbolic. I now understand. I didn’t know then — I gave that guitar away. Why would you do such a thing? I played this guitar at Woodstock! And I wrote songs on that guitar. I played it on so many of the records — “Up Around the Bend,” for instance. I gave the guitar to a 12-year-old boy that asked me if I had any guitars he could have. And I was so forlorn and down in the dumps, thinking I could give away all my problems and just start over. It wasn’t that easy.

What did you learn about those songs all these years later when you rerecorded them?

I was really unprepared for how deep I was gonna have to go. It wasn’t just a guy that sings “Proud Mary” every night. It was a guy trying to be 23 years old, to remember the way the radio was, remember what was going on in the world, and get to that particular space of why and how he had written “Proud Mary.” I learned to make my mind or soul go back to that time. [My wife] Julie told me later she could see me literally doing it by the look on my face. Several months into it, I had a much deeper respect and awareness for what had gone on in 1968 or ’69 — in a sense, I did what the Beatles did, but I did it all by myself. I didn’t have two other guys to write songs with me.

How did you pull off your incredible creative burst in 1969, when you had three classic albums in one year?

Near the end of 1968, I looked at “Suzie Q” and basically said, “Now I’m a one-hit wonder.” I became maniacally obsessed. I was staying up every night, writing songs all day, constantly thinking about what’s good for my band. I managed to come up with those three albums by working harder than anybody else I knew — like working two or three jobs, two or three shifts.

You famously have many disputes with your former Creedence bandmates. But was there something special about that group of people, or do you truly think you could have done it with any other three musicians?

To think that you could just get any old person and then have them play something — I’ve learned through the process of just being a bandleader that that’s hit-and-miss. When my two boys joined the band, it just was there immediately. And that’s biology. I really have to acknowledge that [sons] Shane and Tyler just have the feel I’m looking for, right? So obviously, I think that’s certainly true with [late Creedence rhythm guitarist] Tom [Fogerty]. Even though Tom was limited as a guitar player — he wasn’t full of technique and years of lessons and all that — he certainly had great rhythm and could play great rhythm parts. And the same with Doug [Clifford] and Stu [Cook] eventually.

I think a lot of the process of getting there was that I constantly let them know what I was looking for.… Those are the four people that made those records. And that didn’t particularly happen again in history. So obviously, those four human beings are unique. That might sound like my reserved or side-ass way of giving credit, and I don’t mean it to sound that way. I think the stamp that was put on those records by those four people was arrived at naturally because all of our hearts were in the right place — everybody wanted to arrive at this mysterious place up in the sky. And we got there.

As a kid in 1953, you fantasized about being in a band someday — and in your fantasy, your adult self was a Black man. That’s pretty amazing when you think about how racist that time was.

It’s the same way if you’re nine years old, you can envision yourself being a baseball player, being Willie Mays. The music I loved in the early Fifties was R&B because that was the really most soulful, purest, deepest place I wanted to be. The idea of racism was pretty foreign to me. All my athletic heroes and my musical heroes tended to be Black. I suspended that reality a bit with Elvis, but it did not continue on to Pat Boone. When Pat Boone covered “Ain’t That a Shame,” I thought that was the dumbest thing I’d ever heard in my life.

Later on, did you ever question your right to sing the blues, or to sing a song like Leadbelly’s “Cotton Fields,” which Creedence covered?

I’m very aware of being a middle-class white boy. That question is still looming, by the way, even now. When I wrote “Proud Mary,” I immediately was going “boinin’” and “toinin’” and I don’t even know why. It was many years later, listening to Howlin’ Wolf, I heard him say something similar and went, “Maybe that’s how that got in there.” That all seemed OK if there was the right sincerity to it. If it’s pandering or dumb, I’m gonna slap that guy myself, even if it’s me.

I don’t think there’s any doubt at this point that your songs are gonna live forever. So how does that, if at all, affect the way you look at death?

[Laughs hard.] When you’re watching TV these days, all these medical commercials — they say the side effects may include … and the very last statement is “diarrhea and death.” There’s a song in there for me — “Diarrhea and Death.” I must admit, I really did not notice the clock or the end of the playing field. You hit 80 on the clock and it’s like, “Boy, that’s a scary-looking number!” But I’ve always known my songs would live for a long time. Actually at the moment I created “Proud Mary” — and this was the first time it happened — when I wrote “Proud Mary,” I looked at the page and I went, “Oh, my God, I’ve written a classic.”

Few musicians have ever had such an amazing year as you had in 1969. You released Bayou Country, Green River, and Willy and the Poor Boys. Afterward, things got really tough. I wonder whether it’s possible that you had so much amazing creativity in that one 12-month span that you burned yourself out.

Of course, there was a reason that I produced and manifested those three albums in that year. Right near the end of 1968, in no way was anything assured for my band that I had named Creedence Clearwater Revival. At that moment in time, I told myself that the name was far better than the band was. It was a world-class name, and the band was not world-class. We were still basically a Top 40 jukebox band playing in little clubs in Northern California. I looked at “Suzie Q” and said, “I’m now a one-hit wonder. It took us so long to get here. Now you only get five minutes to do the next step because the spotlight will move on to Led Zeppelin or somebody. It’ll be over for you if you don’t come up with it now.” I literally said to myself, “John, you are just gonna have to do this with music.” I looked around and there was no one in my radar. I’m out in the middle of the ocean in a canoe, and I’m looking all over, and I don’t see anything that’s gonna help me other than whatever I can do with my own two hands.

You haven’t damaged your voice. You can somehow still sing in the same key. What is it that you found vocally that allows it to have that sort of screaming grit, but not tear your voice to shreds?

If you do your screaming in a musical, controlled, effortless way, you won’t ruin it. But if you’re just so passionate that you’re putting all of your mental problems right into your vocals, it can very quickly get ravaged, which has happened to me a zillion times. Another thing that happens to human beings, especially if they’re nervous and tend to internalize their worry like I do — it goes to your tummy. A lot of people get ulcers. On the way to that, you get reflux. Without a doctor’s care and information, you won’t realize that while you’re sleeping, that comes up and hits your vocal cords. Next day you wake up and you sound like Wolfman Jack or somebody. I had a lot of that back in the Nineties and slowly learned to govern my diet, you might say, and just stay calmer.

How do you want to be remembered?

I used to think that I should try to hide all the bad music I made, the things that I did when I didn’t feel very good. I was ashamed of myself living that way. I was a drunk. Alcohol was ruling my existence. And I was miserable and I really didn’t have a lot of sunshine in my life. I was ashamed of the things I was doing and ashamed of myself. And meeting Julie is really the key for me. I eventually overcame that with the help of a wonderful person. During that time, I was trying to stay alive, basically. My existence meant I always felt I was a prisoner of war. The war was against Saul Zaentz. I was in solitary confinement with bright lights, not letting me ever sleep.

And my way of trying to stay sane and fighting back was to stay busy…. But under that situation, the tracks I made were kinda lifeless and stuck in time and rigid and not very joyful at all. I don’t like them when I hear them because of that. I remember how I felt.

I am the luckiest man in the world. I truly feel I lived long enough and met the right person that made me feel lucky for all the right reasons. ‘Cause the real life, the real situation is more important than any career. And the blessed thing that happened was Julie became part of my career. So we do this together. I guess I am a musician that loved music, and I tried to respect that my whole life.