After the tragic 2023 passing of Gabe Hudon, a longtime McSweeney’s writer, editor, and friend, Hudson’s mother, Sanchia Semere, endowed a new award in his honor. Annually, McSweeney’s convenes a panel of jurors to select a writer’s second book-length work of fiction that embodies the spirit of humor and generosity that Gabe and his work did. The first-ever winner of the Gabe Hudson Prize was Ayana Mathis for her novel The Unsettled. Gabe was an unflagging champion of writers and books, and one way to honor the memory of Gabe’s unparalleled enthusiasm and encouragement for writers is to celebrate this award, conferred annually on his birthday, September 12.

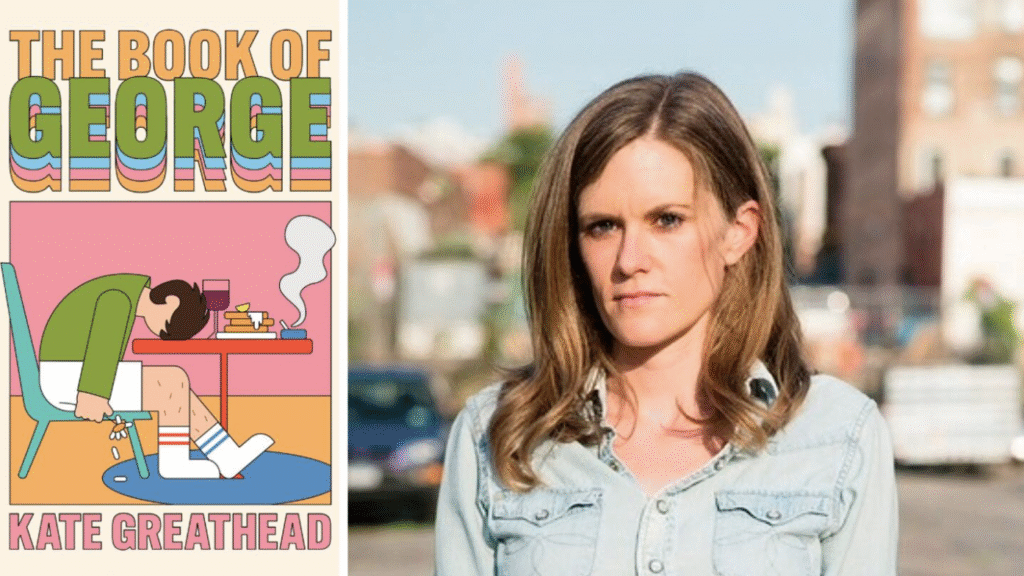

We’re so pleased to celebrate Kate Greathead and her novel The Book of George (Henry Holt & Co., 2024), as the 2025 winner of the Gabe Hudson Prize. The Book of George was also named a Notable Fiction Book of 2024 by The Washington Post, a New Yorker Recommended Book of 2024, and a Best Book of 2024 by Real Simple. Kendal Weaver of the Associated Press calls Greathead “a gifted storyteller who reels off dialogue filled with wit and humor so well it makes page-turning a pleasure…”

The selection committee was led by Akhil Sharma, and this year’s judges also included Caryl Phillips and Deborah Treisman. The committee was fully independent and selected the shortlist and winner entirely autonomously, without input from McSweeney’s editorial staff. Their mandate was to identify an American writer’s second book-length work of fiction that embodies the spirit of humor and generosity exemplified by Gabe and his work. The committee’s citation of the novel says, “An extraordinary artistic achievement in which a character who seems divested from his own life, who responds more than he acts, and often in absurd ways, who never manages to give others what they need from him, remains always deserving of our tenderness. The Book of George covers decades and does so effortlessly, relationships form, couples separate, return to each other both changed and not changed. Always there is love and need urging on new life. The novel can be read as comedy or tragedy or just ordinary life.”

— Amanda Uhle

– – –

NEW YORKERS: Celebrate Gabe’s memory and Kate’s wonderful novel with us on September 13 at Liz’s Book Bar in Brooklyn.

– – –

AMANDA UHLE: I want to start with what Akhil mentioned in the selection committee’s comments, that this novel can be read as “comedy or tragedy or just ordinary life.” As a reader, I was struck by that sense of the ordinary. There are no earthquakes or revolutions here. There are job interviews and apartment moves and an appointment with an auto mechanic, along with all the mundane obligations your characters face. And yet in your pages, the trudge of daily life is not only funny and real, it’s page-turning. Can you talk about how you added so much life to “ordinary life” for George and the other characters?

KATE GREATHEAD: I’m sometimes at a loss when people ask what this book is about. I used to think you had to have something major happen in a novel, and I struggled with this because dramatic plot lines are not my forte. Then I read Evan S. Connell’s Mrs. Bridge. It’s the portrait of a housewife in Kansas City in the 1950s. She lives a conventional life, there are no major revelations or events, and yet it’s utterly compelling.

That was a major turning point for me. It gave me permission to write the kind of book I wanted to write: the story of people living regular lives. I’ve always found ordinary life pretty entertaining. My favorite movies are about this too. Frank V. Ross, Lynn Shelton, Kelly Reichardt, Joe Swanberg—watching their characters behave in ways that could be seen as pathetic or selfish is ultimately so human and relatable (at least for someone like me, who is very in touch with the bowels of my psyche and uncomfortably aware of my less virtuous traits). I can’t get enough of that stuff. It’s a source of inspiration for me—as a person and as a writer. That’s what I’m trying to write.

My mom has this quote on her fridge, Life is beautiful, life is sad. Whenever I’m in her kitchen, I want to take a pen and add, It’s also funny! And the funny part isn’t necessarily distinct from the sad. There’s an overlap.

A writing instructor once told me, “Notice what you notice.” It’s one of the most valuable pieces of writing advice I’ve gotten. Every day there’s some little thing that makes an impression on me: a snatch of dialogue I overhear on the street, an awkward encounter with a neighbor, observations of other people in a doctor’s waiting room, trivial stuff that for some reason or another resonates with me, strikes me as interesting or funny or endearing. Over the years, I’ve made a habit of writing these things down. Much of the content of this book is derived from those real-life moments. I’m reluctant to admit that because it almost feels like cheating. I wish I could say it was all a product of my imagination!

AU: How do you hold on to the many things you’re noticing on an average day in your life?

KG: I write everything down. If something happens that strikes me as potential fodder, I immediately jot it down (usually on my phone), and if I’m unable to in the moment, I get a slightly panicky feeling until I am. It’s a compulsion. I recently drove by a sign that said, “Life is just a series of moments,” and it made me think of something a hypnotherapist (yes) once told me: People cling to physical manifestations of something they can never have. Like if there’s a particular object you collect, whatever that is represents your futile attempt to seek something more significant. I’ve always been tormented by the fact of time passing—that what happened before will never happen again.

AU: After creating and living with such fully realized characters as George and Jenny, how much do you find them lingering afterward? Do they vanish when the book is turned in, or are they still hanging around in your mind at all?

KG: In general, my characters fade when I’m done writing about them, but George has lingered.

He was a fun character to live with because he has such a bad attitude, and there are times when I have a bad attitude. I don’t show it, I try to act like a grown-up, but in these moments it’s cathartic to think of George and how he would respond. Just this week I had a George-like response to a medical situation. I was being a total hypochondriac and exasperating those around me with my incessant requests/demands for reassurance, but I couldn’t help myself. Then I thought of George, and imagining how he would behave helped me see my situation from an external point of view and recognize how irrational I was being, which helped me get a grip. Obviously, I’m definitely not George

AU: Another feature of the novel is its approach to time. I loved watching these characters—driftless George and very pulled-together Jenny—navigate the long road to adulthood. Both characters had ample time to evolve in the story. As a writer, how did you plot out those changes and that growth over decades?

KG: There’s this well-known British documentary series called the Up series. The basic idea: Take a bunch of kids at age seven and film them every seven years of their lives to see how their lives unfold, how they do and don’t change as they grow up. Is the blueprint of the person they become there at age seven? When I was seven, I was chosen to be one of the subjects in the American version of the series (which thankfully never really took off), but which introduced me to the British series, which is a fascinating portrait of people over time.

There’s this expectation in fiction that characters, or at least the ones you care about, evolve over the course of the book, overcoming their issues and ultimately emerging as a better person in a better place. I’ve always wrestled with this, because it doesn’t feel totally true to life. As much as I wanted things to work out for George, more important to me was that his story felt realistic. I’ve known a lot of people like George for whom adulthood does not live up to their lofty, ego-fueled expectations. Guys (I’m sorry to pile on men, but it’s mostly men) who grew up assuming they’d be president or the next Hemingway. And when their dreams don’t pan out, there’s a lot of anger and reluctance to accept that they might just live average, unexceptional lives—and this often results in their making self-sabotaging decisions.

I’ve also known a lot of Jennys, people who do everything right, or everything they feel they’re supposed to do, and yet their lives don’t unfold the way they’d hoped either. I think, for many people, growth is making peace with the discrepancy between our expectations and reality—learning how to be grateful, or at least not bitter, about the hand we are dealt. I didn’t begin writing this book with the goal of depicting that kind of growth; it was something I really only figured out in the process of writing it.

I don’t consciously plot things out beforehand. I wish I were that kind of writer. My husband is, and he can write much faster, which is great because we rely on the sales of his books, but also annoying because my kids are always asking me why Dad has written so many more books than I have—and that gives me a chip on my shoulder. My process is long and messy and disorganized and profoundly inefficient. It’s a process full of panic and doubt and frustration, but is immensely satisfying when it all comes together.