September 12, 2025

3 min read

Child’s Death Shows How Measles in the Brain Can Kill Years after an Infection

A child in Los Angeles County has died from a rare but always fatal brain disorder that develops years after a measles infection. Experts underscore the need for vaccination to protect the most vulnerable

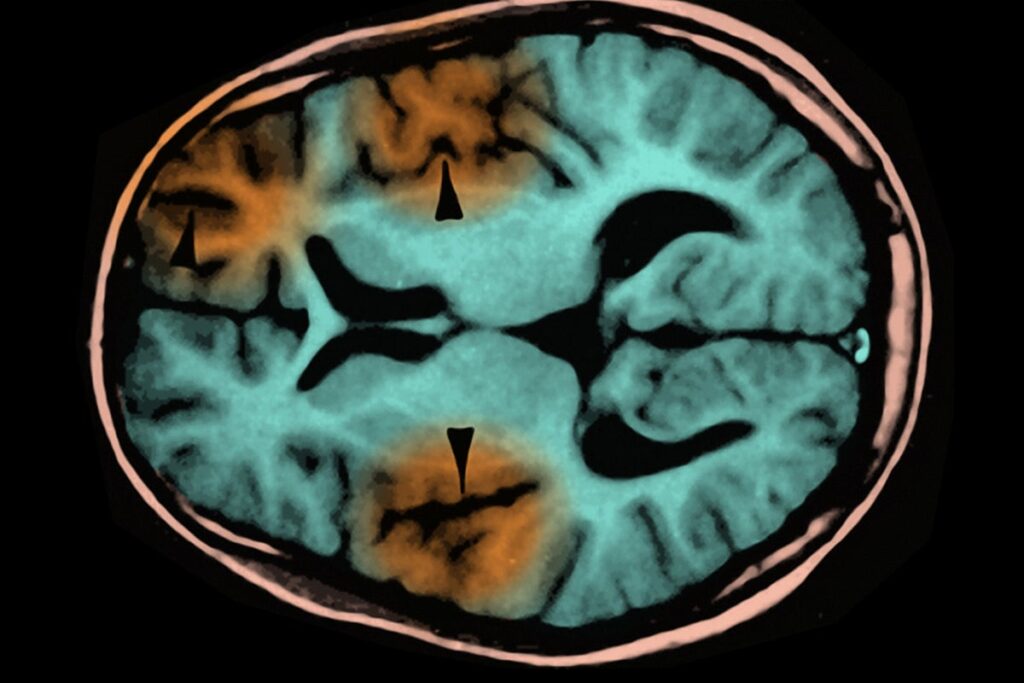

An MRI scan showing subacute sclerosing panencephalitis, a complication of measles infection.

A school-aged child in Los Angeles County has died from a rare but always fatal complication from a measles infection they acquired when they were an infant who was too young to be vaccinated. The first dose of the vaccine is typically not administered until one year of age. Experts say the death underscores the need for high levels of vaccination in a population to protect the most vulnerable against the disease, as well as from side effects that can occur long after the initial illness has passed.

“This case is a painful reminder of how dangerous measles can be, especially for our most vulnerable community members,” said Los Angeles County Health Officer Muntu Davis in a recent statement.

The child who died suffered from subacute sclerosing panencephalitis (SSPE), a progressive brain disorder that usually develops two to 10 years after a measles infection. The measles virus appears to mutate into a form that avoids detection by the immune system, allowing it to hide in the brain and eventually destroy neurons.

On supporting science journalism

If you’re enjoying this article, consider supporting our award-winning journalism by subscribing. By purchasing a subscription you are helping to ensure the future of impactful stories about the discoveries and ideas shaping our world today.

“It’s just a virus that goes unchecked and destroys brain tissue, and we have no therapy for it,” said Walter Orenstein, an epidemiologist and professor emeritus at Emory University, to Scientific American earlier this year.

People with SSPE experience a gradual, worsening loss of neurological function and usually die within one to three years after diagnosis, according to the Los Angeles County Health Department. The disorder affects only about one in every 10,000 people who contract measles. But the risk may be as high as about one in 600 for those who are infected as infants.

“There is no treatment for this. Children who suffer from this will always die,” said Paul Offit, director of the Vaccine Education Center and an attending physician in the Division of Infectious Diseases at Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia, in a previous interview with Scientific American. Offit, who had measles himself in the 1950s, has seen five or 10 cases of SSPE in his career.

SSPE is one of several side effects of measles that go beyond the coughing, runny nose and characteristic rash of the original infection. Measles can also cause encephalitis, a faster-occurring brain inflammation, in one in every 1,000 people who are infected because the virus causes the immune system to attack a protein produced by certain brain cells. This inflammation kills about one in five people who develop it.

Measles also causes “immune amnesia”: the virus seems to attack the immune system’s B cells, which remember previous pathogens the body has been exposed to, resulting in reduced immunity. There is some evidence this effect can last for a couple of years, making those who get measles more susceptible to other infectious diseases.

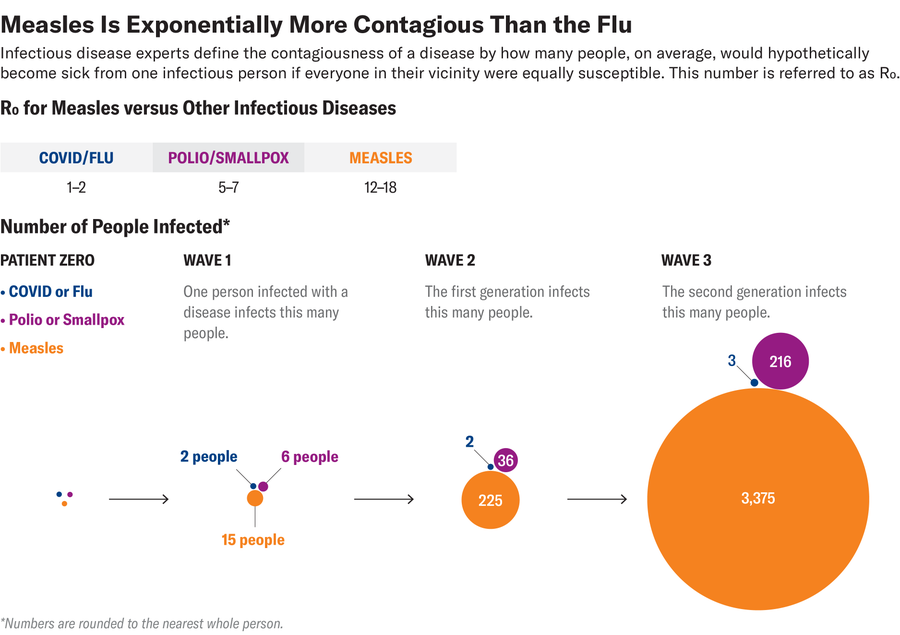

These side effects are of particular concern because the measles virus is highly contagious—an order of magnitude more than seasonal influenza. With measles, viral particles emitted by coughing or sneezing can linger in a room for hours after the infected person has left. One infected person infects 15 more people on average.

This year the U.S. saw its largest single measles outbreak since the disease was declared eliminated in 2000;the recent outbreak occurred mainly in Texas, New Mexico, Kansas and Oklahoma. Most of those infected were unvaccinated or had an unknown vaccination status. Of those infected, 12 percent were hospitalized, and three died of complications from the infection. The fatal cases included the first death of a child from measles in the U.S. in 22 years.

Measles used to infect three million to four million people in the nation every year until vaccines became available in 1963.

The measles vaccine is administered in two doses: typically, the first is given between 12 and 15 months of age and the second is given at four to six years. One dose is 93 percent effective at protection against infection, and two doses are 97 percent effective.

Contrary to claims by Secretary of Health and Human Services Robert F. Kennedy, Jr., measles cannot be treated by vitamin A or cod liver oil. There is no cure or treatment for the disease beyond treatment of symptoms. The only effective means of combatting measles is widespread vaccination. At least 95 percent of a population must be vaccinated to prevent the spread of the disease and to protect either those who are too young to receive it or those who cannot be vaccinated because of other health conditions.

“Infants too young to be vaccinated rely on all of us to help protect them through community immunity,” Davis said in his recent statement. “Vaccination is not just about protecting yourself—it’s about protecting your family, your neighbors, and especially children who are too young to be vaccinated.”

It’s Time to Stand Up for Science

If you enjoyed this article, I’d like to ask for your support. Scientific American has served as an advocate for science and industry for 180 years, and right now may be the most critical moment in that two-century history.

I’ve been a Scientific American subscriber since I was 12 years old, and it helped shape the way I look at the world. SciAm always educates and delights me, and inspires a sense of awe for our vast, beautiful universe. I hope it does that for you, too.

If you subscribe to Scientific American, you help ensure that our coverage is centered on meaningful research and discovery; that we have the resources to report on the decisions that threaten labs across the U.S.; and that we support both budding and working scientists at a time when the value of science itself too often goes unrecognized.

In return, you get essential news, captivating podcasts, brilliant infographics, can’t-miss newsletters, must-watch videos, challenging games, and the science world’s best writing and reporting. You can even gift someone a subscription.

There has never been a more important time for us to stand up and show why science matters. I hope you’ll support us in that mission.