Even in retirement, the space shuttle Discovery exudes power, seen across a hangar crowded with planes and jets at its museum home in Chantilly, Va. Charred and worn from its record 39 missions to space, the stalwart of NASA’s shuttle fleet evokes awe in its one-million-plus visitors every year.

But it won’t be there for much longer, perhaps. Discovery, the showpiece of the Steven F. Udvar-Hazy Center, an annex of the Smithsonian Institution’s National Air and Space Museum, may be removed from its retirement home at the hands of perhaps the most unstoppable force in the universe—politics.

In October came news reports of White House budget office plans to ship Discovery to Houston, removing it from its Smithsonian home at the behest of powerful Texas lawmakers. Uprooting the spacecraft, the workhorse of the space agency’s shuttle fleet, from its Smithsonian owner was previously called “a heist” by Senator Richard Durbin of Illinois during a July Senate Appropriations Committee meeting.

On supporting science journalism

If you’re enjoying this article, consider supporting our award-winning journalism by subscribing. By purchasing a subscription you are helping to ensure the future of impactful stories about the discoveries and ideas shaping our world today.

The threatened move marks the latest turn of the screw on the Smithsonian’s storied space shuttle, a saga that restarted this summer in one of the odder provisions of the Trump administration’s One Big Beautiful Bill Act, signed into law in July. The 331-page tax-and-spending bill provided $85 million to ship the Discovery shuttle to Texas within the following 18 months—to Houston, home of NASA’s Johnson Space Center (JSC) and its adjacent visitor center, the Space Center Houston museum, to be exact.

“Houston has long been the cornerstone of our nation’s human space exploration program, and it’s overdue for Space City to receive the recognition it deserves by bringing the Space Shuttle Discovery home,” said Senator John Cornyn of Texas in a July statement. Cornyn, who is currently in a tight Republican primary battle for his seat in 2026, called Houston the “rightful home” for Discovery in June.

“Exhibiting the Space Shuttle Discovery in Houston would significantly enhance educational opportunities and support the growth of our space economy,” said Space Center Houston president and CEO William Harris in a June letter to Cornyn and Texas’s other senator, Ted Cruz. “Thank you for championing this transformative opportunity.”

Outside of Texas, the reviews have been lackluster.

“Such a move would be a waste of money—a vanity project that is apt to destroy a near-priceless American treasure,” says Matthew Hersch, a fellow in legal history at New York University School of Law and an associate of the Harvard University Department of the History of Science. “The removal of Discovery from the Smithsonian Institution would be a theft, by the federal government, of a $2-billion artifact from a private museum that owns it and has been maintaining it properly for over a decade.”

Art historian Lisa Strong of Georgetown University has similar sentiments: “Discovery is owned in trust by the American people,” she says. “If [Trump administration officials] go in and take it, that’s what [Prime Minister Viktor] Orbán did in Hungary when he went and he took museum objects and gave them to his constituents.”

Removing Discovery from the Smithsonian would be an especially misguided move, Strong adds, because the institution is a world leader in preserving engineering artifacts for future study. The Houston museum simply lacks the Smithsonian’s preservation expertise, she says.

At the end of September, Senator Mark Kelly of Arizona, a former astronaut, joined with Virginia’s senators and Durbin to oppose the movein a letter to the Senate’s overall spending committee. “It is worth noting that there is little evidence of broad public demand for such a move,” they wrote, before warning that the transfer would present “profound financial challenges” and “inevitably and irreparably” damage the shuttle that Kelly flew onboard twice.

The space shuttle Discovery at the Steven F. Udvar-Hazy Center of the Smithsonian National Air and Space Museum.

Dane Penland/Smithsonian National Air and Space Museum

Storied Shuttle

First launched on August 30, 1984, Discovery was the third operational space shuttle NASA built. With more flights under its belt than any of the other four shuttles that went to space, it is referred to as the “Champion of the Fleet.” It launched the Hubble Space Telescope in 1990 and was the first of the pack to be relaunched by NASA after both the 1986 Challenger and 2003 Columbia disasters. Its final mission ended on March 9, 2011. A month later, then NASA administrator Charles Bolden announced that space shuttles Discovery, Atlantis and Endeavour would respectively retire at the Udvar-Hazy Center, the Kennedy Space Center and the California Science Center in Los Angeles. New York City’s Intrepid Museum would receive Enterprise, an Orbiter test vehicle. Bolden said at the time that he chose the locations to “provide the greatest number of people with the best opportunity to share in the history and accomplishments of NASA’s remarkable Space Shuttle Program.”

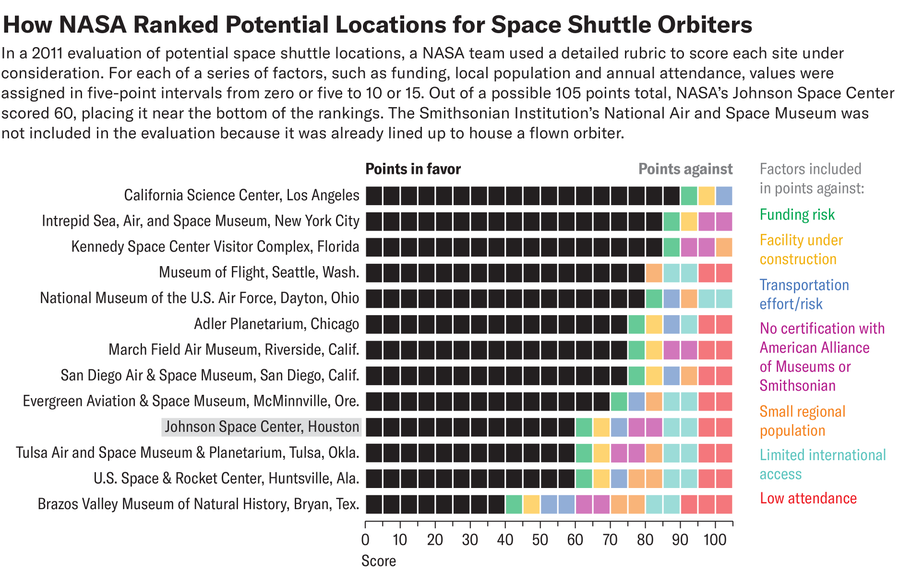

Not everyone celebrated the decision, including lawmakers from Ohio, Utah and Texas, the latter of whom decried it as the “Houston shuttle snub.” In response to complaints from then senator Sherrod Brown of Ohio (home to the National Museum of the U.S. Air Force, near Dayton), NASA’s Office of Inspector General (OIG) initiated an investigation of the decision. Released in August 2011, the report found that Bolden and the space agency had followed NASA’s internal rankings of museums, based on factors such as attendance, funding and museum certification, without political interference (although NASA had delayed the announcement in order for a space-agency-related bill to first pass without any uproar, at the request of the head of a congressional committee). The three winners ranked highest, the OIG report found. Houston, meanwhile, ranked among the lowest entrants, losing out largely because of the museum’s poor funding. “I’m just going to be blunt,” Bolden says. “The reason they were so poorly rated was because Space Center Houston was getting zero support from the city of Houston.”

Other reasons listed included then lower attendance and a lack of international tourists to carry abroad an impression of U.S. space prowess from a visit. Bolden told the OIG in 2011 (as well as in his interview with Scientific American for this article) that Houston would have been his personal choice to house a shuttle. But he was obligated to follow the rankings and the process NASA had chosen for its museum selection. More than a decade later, the retired Marine general and NASA astronaut still sounds surprised at how little interest Texas then had in paying the estimated cost of $42.8-million (in 2011 dollars) for transporting and housing a shuttle.

Amanda Montañez; Source: NASA Office of Inspector General (data)

Bolden was a founding member on the board of directors of Space Center Houston, which opened in 1992, acting as its astronaut office representative from his time at JSC. “We traveled all over the country, trying to find donors and supporters who would help us open a visitor center in Houston,” he says. “And we got zero support from the city of Houston or the state of Texas. They weren’t interested. They were interested in football and other kinds of things but definitely not in putting any money into the Johnson Space Center.”

Now Texas seems to want customers willing to pay $30 for tickets to the Houston space museum. Houston is hurting, as space cities go, with JSC looking at budget cuts demanded by the Trump administration, journalist Joe Pappalardo noted in Texas Monthly in September. “If Houston manages to hold its Space City title, it could have powerful political friends to thank,” he wrote, referring to Ted Cruz, who chairs the Senate’s spending committee, and Representative Brian Babin, whose district includes JSC. Cruz and Babin have also been instrumental in bringing $4.1 billion in moon-mission cash and $300 million in planned “improvements” to the space center in Houston though the July spending bill.

Space shuttle Discovery rolls into its hangar for display at the Smithsonian in 2012.

Dane Penland/Smithsonian’s National Air and Space Museum

A Technical Challenge

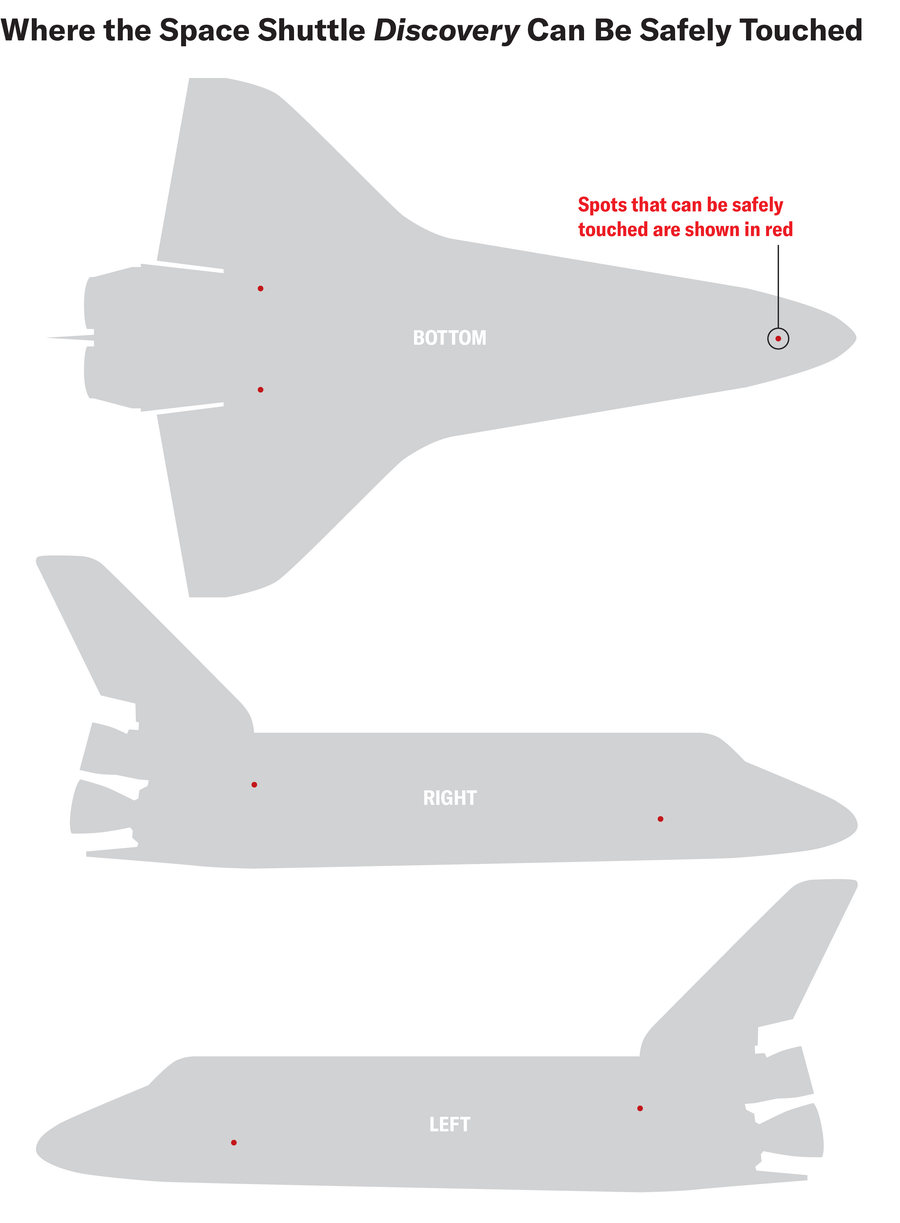

Moving the shuttle is likely to be tricky and risky. Its 24,300 ceramic tiles, for example, are made of a glass-coated silica that is 90 percent air. They’re so fragile that fingertip pressure can break them. Workers have cracked tiles by bumping the objects with their head or with a broom handle while sweeping underneath. Roughly four out of five tiles on Discovery have already been weakened during one or more of the shuttle’s 39 re-entries from space. A square foot of tiles cost $10,000 to make and install back when they were being manufactured in the 1980s. That capability has long been scrapped.

Amanda Montañez; Source: NASA (reference)

Smithsonian museum personnel have estimated it will cost $305 million to transport Discovery to Houston and safely house it in a new display. Simply relocating the shuttle, the costs of building a facility to safely house and display it aside, will cost $120 million to $150 million, according to a joint Smithsonian and NASA estimate sent to the White House budget office in late September.

A July Congressional Research Service report noted that a private company has suggested that it could instead move the shuttle by ground and barge from Virginia to Houston for $8 million, far less than the Smithsonian’s estimate.

Yet a highly experienced expert on transporting space shuttles calls that number laughable, speaking anonymously for fear of sparking calls for his own investigation from Cornyn. “There is no meaningful way to move this vehicle at this point without reconstituting a huge amount of capability that we shut down 10 years ago,” the expert says. Strong agrees. “I’m pretty sure we know who knows how to move, and care for, museum artifacts,” she says. “I think I’d go with the Smithsonian’s estimate.”

In a statement to Chron in an article published on October 6, Cornyn’s office derided the cost concern, saying, “Discovery belongs in Houston, and will make the journey there safely, securely, and efficiently in accordance with the law whether the woke Smithsonian and its cronies in Congress like it or not.” (In an e-mail to Scientific American, Tatum Wallace, Cornyn’s press secretary, said that statement came in response to “the Smithsonian spreading lies about the logistics for moving Discovery.”)

On that date, Cornyn and Cruz sent a letter to the leaders of Senate’s appropriations committee, urging them not to pause spending on Discovery’s relocation over cost concerns. “As part of its opposition effort, the Smithsonian has disseminated misinformation about the logistics of the move, falsely claiming that the shuttle’s wings would need to be removed for transport, a claim not supported by industry experts,” the Texas senators wrote.

But transporting Discovery by highway and barge to Houston is simply a nonstarter, according to the expert. It’s too big to fit under highway overpasses, meaning the fragile spacecraft will need to be taken apart and transported by truck, something now reportedly under consideration by the White House. In October NASA and the Smithsonian warned Congress that such plans “would likely require taking it apart” and could irreparably damage the shuttle. Even taken apart, an intercoastal waterway barge trip from Washington D.C. to Houston would be an epic engineering feat because shuttle tiles are easily damaged by moisture. (And the last time a barge trip was tried, in 2012, the Enterprise suffered minor damage from a railroad bridge support as it was being moved between New York City and Jersey City, N.J.)

That leaves rolling Discovery from the Udvar-Hazy Center to the nearby Dulles International Airport (there is a connecting road between them), loading it onto a Boeing 747 and flying it to Texas as the most feasible way to move the shuttle. But that strategy has problems, too. Only a handful of people alive even know the necessary procedure for retracting the shuttle’s landing gear, and they might not care to unretire for the job. The Air and Space Museum’s James S. McDonnell Space Hangar, now centered around Discovery, has two hangar doors but would need a hole cut for the shuttle’s tail to exit. “Just getting it ready is going to take you a couple months and several million dollars just to make sure you don’t hurt it when you move it,” the technical expert says.

What’s more, the two 747’s configured to carry the space shuttles were decommissioned more than a decade ago. One, Shuttle Carrier Aircraft 911, is parked out in the desert in Palmdale, Calif., and could be inspected to fly for about $10 million, with about that same amount needed for four new engines. It would likely cost a few million dollars more to reinforce it again for carrying the shuttle. Pilots would need to be retrained in the unique takeoff procedure required to counterbalance the 170,000-pound shuttle squatting atop the jet. And ironically enough, the second 747 was cut up and moved to Space Center Houston, where it was rebuilt for exhibition, making it unrecoverable.

Houston’s Ellington Airport is only eight to 10 miles by road from Space Center Houston, but safely moving a space shuttle isn’t easy or cheap. Moving the space shuttle Endeavour just 12 miles from Los Angeles International Airport to the California Science Center was an arduous engineering feat that cost roughly $10 million. The shuttles “were designed to be moved carefully by a large crew of trained people using a lot of specialized ground equipment,” says the technical expert. “That’s all been scrapped.” That includes self-propelled modular transporters and special slings that carried the shuttles, attachable only at seven points on the fuselage.

The Big Beautiful Bill requires the space vehicle must be transferred by January 4, 2027. That’s a little less than 15 months away, meaning all that planning—and spending—needs to start now.

The space shuttle Discovery carried atop a Boeing 747 aircraft on its 2012 transfer flight to the Smithsonian.

Dane Penland/Smithsonian National Air and Space Museum

A Political Challenge

An even bigger problem for moving Discovery to Houston is that NASA doesn’t own the shuttle anymore. The Smithsonian took title of the spacecraft from the space agency in 2012. Noting this, the Congressional Research Service wrote in its report that NASA’s ability to purloin Smithsonian space artifacts “is unclear and may be subject to question.”

“The Smithsonian Institution owns the Space Shuttle Orbiter Discovery and holds it and all of its collections in trust for the nation,” says Alison Wood of the Smithsonian Institution, who noted the museum’s charge to preserve artifacts for future generations of scholarship and presentation. “The Smithsonian will carefully evaluate any request to move Discovery in light of these obligations.”

Steven Dick, a former NASA chief historian, acknowledged that politics always plays a role in these types of decisions. Both JSC, where astronauts lived, trained and managed flights, and the Smithsonian, the official depository for NASA artifacts, have claims to the shuttle, he says. But in an outdoor shed, JSC already has a Saturn V moon rocket on display, something the Smithsonian lacks. “So one might whimsically say JSC could swap their Saturn V for Discovery, but that would cost even more money,” Dick says.

“This will be the first time ever in the history of the Smithsonian that someone has taken one of their displays and forcibly taken possession of it,” Durbin said during the Senate Appropriations Committee meeting in July. “What are we doing here? They don’t have the right in Texas to claim this.”