October 14, 2025

3 min read

November 2025: Science History from 50, 100 and 150 Years Ago

Curveballs; poison wallpaper

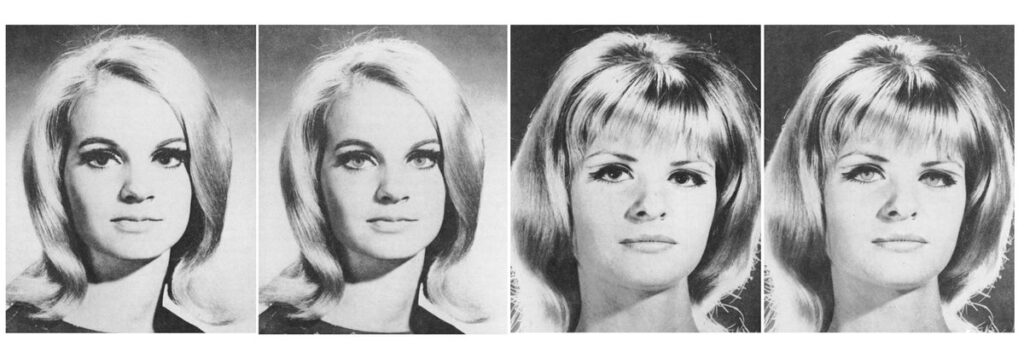

1975, Pupil Perception: “Photographs of two women were retouched so that each woman had large pupils in one photograph and small pupils in the other. Male subjects were shown eight different pairs of the photographs and were asked in which picture did the woman appear to be more sympathetic, selfish, happier, angrier and so on. When the question concerned a positive attribute, subjects tended to choose the woman with the large pupils; for a negative attribute, they tended to choose the small pupils.”

Scientific American, Vol. 233, No. 5, November 1975

1975

Engines for the Eighties

“A comprehensive study by the Jet Propulsion Laboratory vigorously urges that a $1-billion program be launched to develop a new automobile engine for introduction by 1985 or sooner. After observing that ‘the automobile will maintain its dominant role in personal transportation through the foreseeable future,’ the study concludes that two engines, the gas turbine and the Stirling-cycle engine, promise significantly greater fuel economies than such widely discussed alternatives as the diesel engine, the Rankine (steam) engine, the all-electric car, hybrid configurations or any improvement in the present Otto-cycle engine. A fully developed gas-turbine engine should provide about 22 percent more miles per gallon than an equivalent fleet powered with a maximally improved Otto-cycle engine, and a Stirling engine should show an even greater improvement of about 35 percent.”

On supporting science journalism

If you’re enjoying this article, consider supporting our award-winning journalism by subscribing. By purchasing a subscription you are helping to ensure the future of impactful stories about the discoveries and ideas shaping our world today.

1925

Turn Mercury to Gold

“In 1924 Professor Adolf Miethe of the Charlottenburg Technical College in Germany announced that he had solved the time-honored problem of transmuting one of the base metals into gold. If a quantity of pure mercury was exposed for several hours to an intense electric arc inside a vessel of quartz, a small proportion of this mercury was transmuted into gold. If true, this experiment constituted a scientific revolution. Feeling obligated to discover the truth, the Scientific American arranged for a comprehensive and exact test in the laboratories of New York University. Work was begun in December 1924 and has continued, the Scientific American supplying a portion of the necessary funds. The result may now be announced. It is an entire failure to confirm the transmutation of mercury into gold.”

Curveball

“We give readers the best answers science knows, and then 50 years later the ghost of our statements sometimes rises to plague us. Recently in the New York Telegram, John Doyle, vice president of A.G. Spalding and Brothers, was quoted as saying, ‘In the July 28, 1877, issue of the Scientific American is a query asking if it is scientifically possible to pitch a baseball so as to describe a horizontal curve in the air. The editorial answer was: We have never seen it done. This led to a long public discussion, which finally resulted in a practical demonstration of curve pitching on the Cincinnati baseball grounds on October 20, 1877.’ Since that day we have seen curve pitching that seemed to us both science and art raised to its apex.”

Airship Breaks in Two

“The dirigible Shenandoah was wrecked over Ohio in a furious thunderstorm that flung her 4,000 feet upward into the heavens. The sudden thrust set up a violent vertical bending stress. Commander Lansdowne valved her freely, pointing her nose down with engines running. She came down with such rapidity that he had to discharge water ballast and order the dropping of gas tanks. She was brought to a level keel at about 3,000 feet but suddenly broke in two. The integrity of this delicate framework depends on its being everywhere supported by the upward pressure of the bags of gas within it. Deflate two or three bags and the ship will sag and break her back. She broke also near the control car, which had been sheared off and fell, killing everyone in it. The 75-foot section, with gas bags deflated, fell swiftly, throwing out its occupants. The nose, relieved of the control car weight, rose, and the personnel, by valving, brought it to earth, and the occupants of this portion were saved.”

1875

Poison Wallpaper

“Cases of arsenical poisoning occasioned by living in rooms, the walls of which are covered with paper colored green by arsenite of copper, have frequently been recorded. A recent case, writes Professor Cameron, was caused by inhaling the dust from paper not colored green. The family of Mr. Jones, at New Ross, [Ireland], suffered so severely from symptoms usually produced by arsenic that he was induced to get the wallpaper of his house examined. Out of seven kinds of paper, six were found to contain arsenic.”

It’s Time to Stand Up for Science

If you enjoyed this article, I’d like to ask for your support. Scientific American has served as an advocate for science and industry for 180 years, and right now may be the most critical moment in that two-century history.

I’ve been a Scientific American subscriber since I was 12 years old, and it helped shape the way I look at the world. SciAm always educates and delights me, and inspires a sense of awe for our vast, beautiful universe. I hope it does that for you, too.

If you subscribe to Scientific American, you help ensure that our coverage is centered on meaningful research and discovery; that we have the resources to report on the decisions that threaten labs across the U.S.; and that we support both budding and working scientists at a time when the value of science itself too often goes unrecognized.

In return, you get essential news, captivating podcasts, brilliant infographics, can’t-miss newsletters, must-watch videos, challenging games, and the science world’s best writing and reporting. You can even gift someone a subscription.

There has never been a more important time for us to stand up and show why science matters. I hope you’ll support us in that mission.