O

n October 14, the iconic singer D’Angelo died of pancreatic cancer at 51. Tributes and recollections of the Brown Sugar, Voodoo, and Black Messiah artist poured in from all over the world, including from legendary photographer Eric Johnson, who posted never-before-seen pictures he took of the soulman in the nineties. Johnson, who’s shot the likes of Notorious B.I.G, J Dilla, Lauryn Hill, and directed Maxwell’s “Til The Cops Come Knockin’” music video, told us about his chance first encounter with D’Angelo in the nineties, and hanging out with him during a guerrilla-style photoshoot.

Back in the nineties, my best friend was Sarah Anne Webb from [British band] D’Influence. She would come to New York [and] hang out with me. I had this little ‘66 Mustang convertible we’d drive around the city. My friend had a photo studio on 25th Street [in Manhattan], and there was a recording studio a couple of doors down that all the rappers used to work in. One day, me and Sarah were parked on the street. It’s a summer day, just chillin’.

We see this dude, little guy, [and] she thinks he’s cute. So she yells from across the street, “Yo, you like fat girls?” And he was like, “Hell yeah!” That was the first exchange I ever had with D’Angelo. I didn’t know who he was at that point.

[One or two years later], Interview Magazine hit me up and said that they wanted me to shoot three upcoming artists. I didn’t have a studio, so I was like, “I’ll invite them to Brooklyn to my apartment and take them on the roof.” Sarah was staying with me [at] this particular moment as well. Three [acts] came: this band called Brooklyn Funk Essentials, Faith Evans, and D’Angelo. Sarah says to me, “Yo, that’s the dude that I asked if he liked fat girls.”

When you look back, it’s so interesting. What were the chances that I would be with this big girl who would ask D’Angelo if he liked fat girls? And then for him to show up at my house? It was so interesting that I was hanging out with Sarah this time [as well] because she lived in London. I feel like something drove us to each other in the most chill, genuine way. There’s lots of blocks in Manhattan. There’s lots of hours in the day.

I felt like [at the shoot] D’Angelo was a bit detached from being in a group. You could tell when people are intermingling and [being personable] vs. someone who’s kind of like, “I’ll just stand over here by myself.” The idea of all of these people being introduced together…when you look back, you can tell that’s not necessarily D’Angelo’s style. So it was a dry photo with all these people. When he got back to Interview, they were like, “You know what? Let’s just do everybody separate.” So I shot all of ’em separately, and me and D’Angelo became cool. We didn’t have a budget, I would always have a 4 x 4, like a Jeep Pathfinder or something like that.

I would just meet somewhere and whoever I was shooting would hop in the Jeep and we’d drive around and [take] photos. That’s my thing anyway, I feel like I’m good on the spot. When I was young, I would like to see those photos in London of those punk bands, Sid Vicious and shit. It’s just something about that badass attitude. I feel like because I came into the scene with alternative-punk taste, I was turned on by raw photography [where] you could see a picture of The Clash on the street. That inspired me to shoot people like that. I felt like if you are in middle America or any place and you have this idea of New York, what would be cooler than the idea that you could go to New York and run into D’Angelo on the street?

I always wanted to give people outside of New York a really normal idea of what it could be out with the homies hanging out. Playing music, getting stoned or whatever, but documenting it and taking photos. And you can see in the photos [with D’Angelo], he’s smoking blunts in some of the photos. It wasn’t like we felt like smoking blunts or whatever was druggie. Everyone smoked, but everyone was getting their work done. I mean, you’d look back at what he was producing. It was insane.

I posted a photo yesterday and told a little bit of that story. It’s my most popular photo of all time. We’re all young. We’re driving around listening to new music, listening to demos, talking about music [and] what we were working on. It was mostly talking about music, because when you look back, it really was so many badass records coming out all the time. So I was really psyched to be a part of it. Everyone’s kind of checking out what other people are doing. [Those] were my first couple of [exchanges] with D’Angelo. Our personalities were really compatible and cool. If you were in shoots, an artist would bring a cassette or CD of their demos. So anytime you’re going to meet an artist, you’re going to hear something. I felt like the first time [I heard his music] it was him [playing it], but then he started building up steam, doing radio, videos, and things like that.

Eric Johnson

I asked [photographer Jamel Toppin], who was my assistant that day, if he remembered anything about [shooting] D’Angelo. He [messaged back], “I rolled 1 million Blunts. It was the day that you and I first met, actually. I was working in a Supreme store. I left on my lunch break and came to meet you with my portfolio. I had a pound of weed in my backpack that day. You hired me on the spot, I called the store and quit, and we went out to shoot D’Angelo that afternoon. He smelled the weed and became super pumped. He had a five-pack of Phillies in his pocket. I used to see him around the city a lot over the years. And every time he remembered that day. Outside of the [shoot for] album packaging, I think that was one of his first shoots because [“Brown Sugar”] had just come out.”

You can see my assistant in the back of D’Angelo [in one of the photos] because we have the trunk of the 4 x 4 out, it’s kind of like a studio. That’s funny: Imagine having a five-pack of the Phillies and not the weed. That means you’re going to bring something to the table. I think it’s adorable. But he also knew who he was; he was going to find somebody with weed.

Dominique Trenier, [D’Angelo’s former manager], was one of my friends, [and] got in trouble somehow [one day in the nineties]. We were in court [at the same time]. Everyone’s waiting to get their time in front of the judge so they could decide how much you’re going to get, and I was like, “Is that fucking Dominique Trenier?” I happened to go Club Trinity [later that night], Dominique and D’Angelo are [there]. Dominique was like, “Yo dude, was that you in court?” And I was like, “Yeah, what was you there for?” He’s like, “I can’t even get into it.” But it set the tone on just how live we all were. Clearly D’Angelo was a little bit live too.

When we were hanging out in the club, he and Dominique were saying how crazy it was that he couldn’t get signed in the beginning. It was still at that stage where you’re like, “Wow, this is happening.” Everything that was going to happen hadn’t happened yet. I remember seeing the video for the “My Lady” remix, Erykah and all those girls in it. I was like, “Wow, this guy really is doing something.” It was cool to watch because he was the homie. He was so nondescript, the way that we chilled. He wasn’t walking around like a rockstar, and you can tell in those photos. I just like the idea of getting people at a certain time, when they’re just about to [blow up].

There’s something so soulful about D’Angelo. His integrity musically was just so layered. At his peak, which I would say is the Voodoo album, you put that up there with Prince or Sly Stone or something. He’s definitely one of those greats at his peak. Some people argue that the shelf life was not so long because of the amount of time and the amount of product. But if someone puts out something that’s fucking good, I don’t care how much they put out. D’Angelo didn’t put out that many albums, but Voodoo is up there, production wise, with the best albums of all time.

Without social media, you kind of lose touch a little bit. For some reason I wasn’t ever the type to follow up relationships with any of the artists I worked with. The ones that I stayed the closest with were the ones who would hit me up all the time. I remember that day he gave me his number and I just looked at it because I was like, “What am I going to do with this? What the fuck am I gonna call D’Angelo for?” [Laughs]

If one of my assistants worked with another photographer and D’Angelo shot with him, he’d be like, “Yo tell Eric I said, ‘What’s up?’” So that was it, because you never really think you’re not going to see each other anymore. You don’t remember when you [stop] seeing anyone because you’re just in the moment. But then you look back and you be like, “Oh shit, I haven’t seen [that person] in a while.”

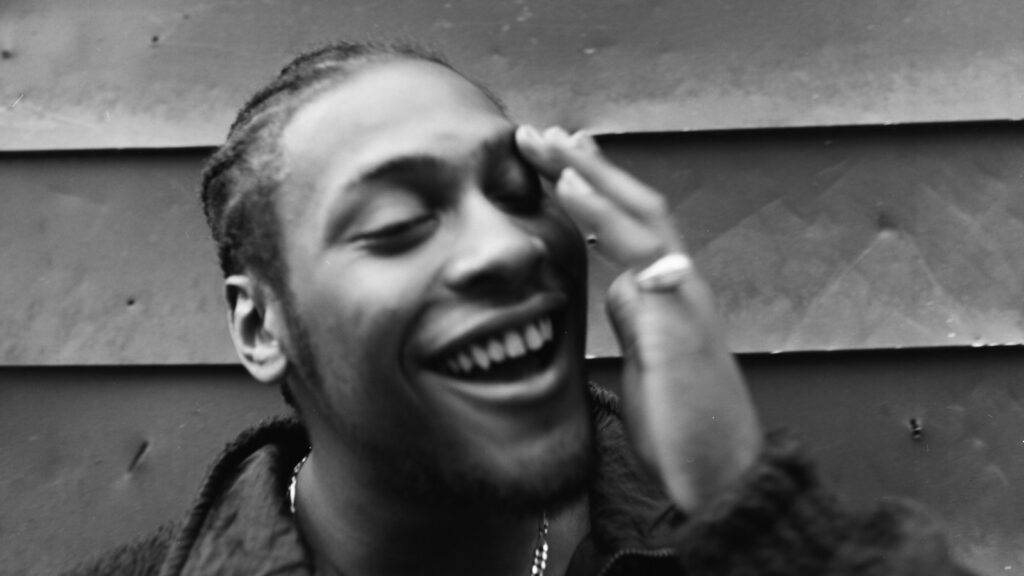

I remember when I found out [he passed], my friend Rosie Perez [called] like, “Are you okay?” And I was like, “What?” She’s like, “D’Angelo died.” I was like, “No, absolutely not. It was wild.” In the beginning I was so depressed. Then I looked through the photos. I just happened to have that album. It made me not so sad. I was like, “Wow, I’m really glad to be a part of that.” And so many people are part of his existence. I saw that one where he was smiling, and I never noticed that photo before so I shared it. I feel like [that] slice of life is really sweet and enduring and honest. He looks very endearing in his youth and smiling. I love being able to tell that story in my photos

A couple of years ago when I was on vacation, I was with my friend Molly Hunter, and she had a studio. Angie Stone called us in Malta to talk to Molly because she wanted Molly to help her son record at her studio. Molly was like, “I’m with my friend [Eric].” And even though I never shot Angie Stone, she put me on the phone with her. I was telling Angie, “Oh, I love you, blah, bla.” but she was more like, “Take care of my friend Molly.” I gave the phone back, and then when Molly got off the phone, she said, “D’Angelo was there [with Angie] too, and he was like, ‘Yo, that’s my boy. He was photographing me all the time back in the day.’”

I just thought [with how we] lost touch with each other all that time, to say my name and he’d be like, “Yo, that’s my boy,” that was a really funny detail. That’s the last thing I’ve ever heard [from him] after all these years. He was still like, “Yo, that’s my boy.”