The Titanic lies about 12,500 feet under the ocean. The pressure down there is so immense that even submersibles supposedly built for those conditions can, as we know, tragically fail.

Now imagine taking a sub nearly three times deeper.

That’s what an international team of scientists did last summer. Led by the Chinese Academy of Sciences, the researchers took a manned submersible to the bottom of deep-sea trenches in an area in the northwest Pacific Ocean, roughly between Japan and Alaska, reaching a depth of more than 31,000 feet.

The researchers weren’t looking for a shipwreck. They were interested in what else might be lurking on the seafloor, which is so deep that no light can reach it.

It was there that they found something remarkable: entire communities of animals, rooted in organisms that are able to derive energy not from sunlight but from chemical reactions. Through a process called chemosynthesis, deep-sea microbes are able to turn compounds like methane and hydrogen sulfide into organic compounds, including sugars, forming the base of the food chain. The discovery was published in the journal Nature.

This was the deepest community of chemosynthetic life ever discovered, according to Mengran Du, a study author and researcher at the Institute of Deep-sea Science and Engineering at the Chinese Academy of Sciences.

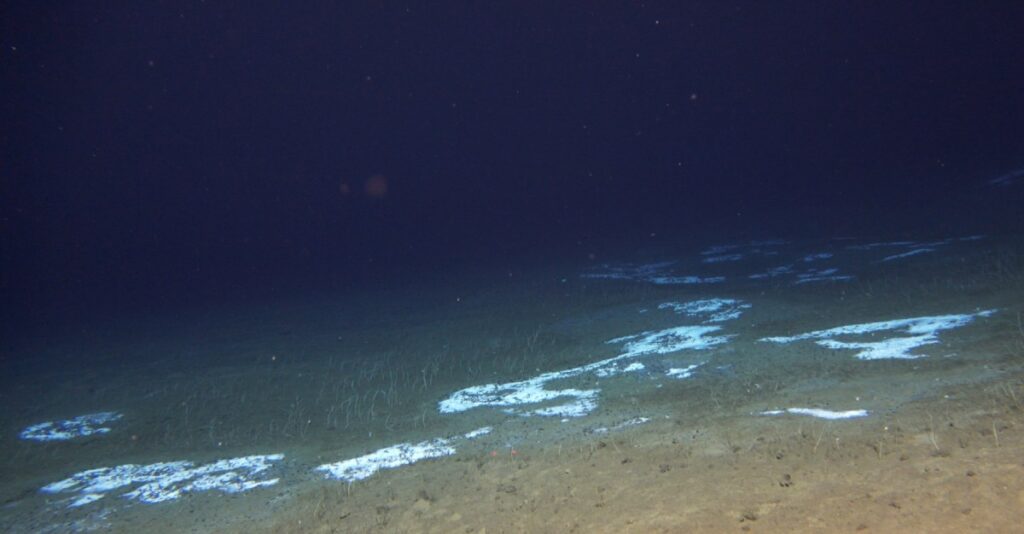

Using a deep-sea vessel called Fendouzhe, the researchers encountered abundant wildlife communities, including fields of marine tube worms peppered with white marine snails. The worms have a symbiotic relationship with chemosynthetic bacteria that live in their bodies. Those bacteria provide them with a source of nutrients in exchange for, among other things, a stable place to live.

Among the tube worms the scientists encountered white, centipede-like critters — they’re also a kind of worm, in the genus macellicephaloides — as well as sea cucumbers.

The researchers also found a variety of different clams on the seafloor, often alongside anemones. Similar to the tube worms, the clams depend on bacteria within their shells to turn chemical compounds like methane and hydrogen sulfide that are present in the deep sea into food.

Unlike other deep-sea ecosystems — which feed on dead animals and other organic bits that fall from shallower waters — these trench communities are likely sustained in part by methane produced by microbes buried under the seafloor, the authors said. That suggests that wildlife communities may be more common in these extremely deep trenches than scientists once thought.

“The presence of these chemosynthetic ecosystems challenge long-standing assumptions about life’s potential at extreme depths,” Du told Vox in an email.