- The murder of Elizabeth Short, dubbed the Black Dahlia by the press, has long captured the interest of true crime buffs.

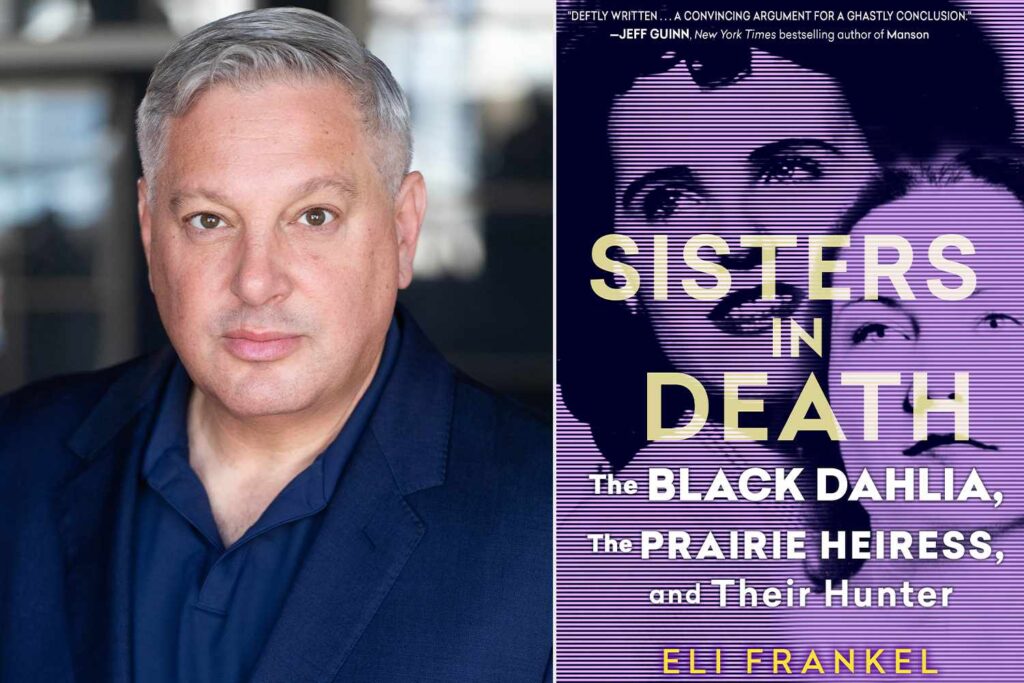

- Now a new book, Sisters in Death: The Black Dahlia, the Prairie Heiress, and Their Hunter by Eli Frankel, offers a possible solution to the case.

- EW shares an exclusive excerpt from a key witness, the woman who discovered Short’s body.

Few cases have haunted Los Angeles the way the Black Dahlia murder has.

The still unsolved homicide of young aspiring actress Elizabeth Short has generated scores of books, TV specials, and theories over the years. Now, a new true crime entry, Sisters in Death: The Black Dahlia, the Prairie Heiress, and Their Hunter by Eli Frankel, seeks to solve the crime definitively.

In January 1947, Short’s body was found dissected and drained of blood in an empty lot in Los Angeles. The race to find her killer and resulting city-wide hysteria captured the world’s attention — and the murder remains unsolved nearly 70 years later despite numerous attempts to close the case.

Citadel

Frankel’s book posits that Short and Leila Walsh, a Kansas City heiress who was murdered in 1941, were killed by the same man. Frankel uses newly discovered documents, law enforcement files, interviews with the last surviving participants, the victims’ own letters, trial transcripts, military records, and more to piece together this complex puzzle.

The book, which hits shelves Oct. 28, hinges on a key witness, the woman who discovered Short’s body. In this exclusive excerpt below, we learn more about the day that Betty Bersinger happened upon one of L.A.’s most gruesome deaths.

Excerpt from Sisters in Death: The Black Dahlia, the Prairie Heiress, and Their Hunter by Eli Frankel:

It is one of the most infamous moments in the annals of true crime, an encounter of such stark and shocking contrasts that it has become the de facto introduction to nearly every narration of the greatest cold case in United States history. Some of the details may subtly shift between each retelling, but the story always remains the same and never ceases to grab attention.

On the morning of January 15, 1947, in the quaint, working-class neighborhood of Leimert Park in South Central Los Angeles, twenty-seven-year-old Betty Bersinger set out to walk the few short blocks between her home and a nearby commercial district where she intended to get a pair of shoes fixed. Accompanying her was three-year-old daughter, Anne. On her regularly traveled route down Norton Avenue, Betty would pass a weed-strewn lot, two blocks in length.

Housing construction had suffered during World War II, but now this stretch of empty real estate stood at the ready to join the suburban sprawl surrounding it on all sides. Parcels on the block had been subdivided, depressions in the curb laid for future driveways. For years, the expanse of dirt and weeds had served as a convenient location for locals to dump trash. On the morning of January 15, it became a convenient location to dispose of a corpse that would redefine the city of Los Angeles.

Some versions have Anne playing in the weeds, then suddenly crying out for her mother’s attention. Other versions have Betty pushing Anne in a stroller, stopping abruptly when she sees it. She then runs screaming in terror to the nearest house. Yet other versions claim Betty calmly walked on, having glanced to her side only for a moment and mistaking what she saw for a mannequin. Farther down the block, she realizes something is not right and calls the police to investigate.

Remaining consistent across all versions of the story is what Betty encountered at 10:50 a.m. on January 15, 1947: the body of twenty-two-year-old Elizabeth Short, cut neatly in half, the two parts facing up and separated by a gap of several inches. Horrific wounds across the body detailed a map of torture. Large pieces of skin and flesh were carved out and missing. Various knife and razor cuts had been made across the body, some in graphic crosscross fashion, others a flurry of tiny slices, yet others prominent and deep. Dark, circular depressions around her neck, wrists, and legs evidenced long periods of restraint by leather or wire before her death. Even more shocking was what had been done to her face. Three-inch gashes had been ripped from both corners of her mouth nearly to the ears, forming a contorted, twisted smile. The body had been drained of blood and scrubbed clean with a coconut-fiber brush, appearing stark white in the sun, in contrast to the victim’s jet-black hair.

Photographs of the horrendous scene were cleaned up for newspapers, a pretty face in repose painted over the ghastly carved cheeks and a blanket artistically added to cover the bisection. Though the mutilations would not be publicly viewed, the description in print alone was enough to grip the imagination of Angelenos and propel the story to the front pages of newspapers across the country.

One fact of the crime scene grabbed the most attention and remains to this day the most puzzling, tantalizing, and frightening aspect of the discovery of the body. No description of the case ever fails to mention it. In fact, it has become the defining feature. The body wasn’t discarded in a back alley, or left in a car, or hidden in a home. It had been laid out in the grass mere inches from a heavily trafficked public sidewalk. A streetcar line emptied out hundreds of passengers daily just a block away. The two halves of the body had been carefully placed, lined up, and posed for public view on Norton Avenue, with its considerable foot traffic from dawn to dusk.

No doubt the location had been chosen for a reason. The empty block in the early morning hours would have allowed the killer a modicum of privacy when the body was laid out, but by sunup, the display of a bisected, heavily tortured corpse inches from the sidewalk guaranteed an audience and maximum shock value. Whoever did this wanted the world to see their work.

Betty Bersinger would be the person fate chose to discover that work. The press could not have found a more ideal first witness to the horrifying display. Here was the postwar American housewife—neatly dressed, pretty, poised, active—stepping unwittingly into a scene of utter depravity and sadism that reflected back at this wholesome young mother the darkest recesses of the human mind. In a world still grappling with the horrors of war and the evil men visit upon each other, Betty Bersinger became a stand-in for every American trying to normalize their lives after years of trauma.

Bersinger was hounded by the press, to whom she told and retold her story. Different reporters injected their own flare for the dramatic, which became the source of discrepancies in her story. Though she closely guarded her privacy, Bersinger would allow a handful of interviews in later decades, and her account remained remarkably consistent. Her memory of that day never flagged, every detail remaining crystal clear, her story never deviating.

As Betty explained, “It was about the time kids were going off to school, riding their bikes or whatever, and I had to go by this lot that was undeveloped . . . And as I was walking along, I happened to glance over at my side and I saw this strange sight. It looked like a mannequin that had been cut in half and was separated and was lying there. And I didn’t glance at it too long because I had my little girl with me. And I thought, ‘gosh,’ as I walked on further. I thought that just didn’t seem right to me. And I could see these kids with their bicycles, and I said maybe it’ll scare those kids if they ride to school and see this, so I better call somebody to come and at least have a look and see what it is. But the thought of a dead person did not enter my mind. I thought it was a mannequin because it was so white.”

In another interview, she offered even more detail regarding the body. “I glanced to my right and saw this very dead, white body. My goodness . . . it was so white. It didn’t . . . look like anything more than perhaps an artificial model. It was so white and separated in the middle. I noticed the dark hair and this white, white form.”

Bersinger’s accounts prove she did not just casually glance for a moment to her side and walk on, unsure of what she saw. The sight was so striking that it burned an image into her memory she would never forget. Likewise, for anyone who has seen the photographs of the bisected body of Elizabeth Short, the image is unforgettable.

Los Angeles Herald ExaminerPhoto Collection/Los Angeles Public Library

But there is a problem with Bersinger’s story. In every interview, she consistently states she saw a truncated white form with black hair. The figure was so white she believed it was a mannequin. But the photographs of the body on Norton Avenue display a horrifically tortured form, gaping areas of open muscle and flesh, visible organs, a ten-inch open laceration across the face, overwhelming trauma to the head—all within inches of where Bersinger was standing. Nobody could mistake the form visible in those photographs for a white mannequin.

When investigators and reporters arrived minutes after Bersinger called the police, they would experience utter shock and horror, even after years of exposure to the worst crime scenes in Los Angeles. Their memories of that day would fill books and articles for decades to come, and none of them would describe anything resembling a mannequin. Betty Bersinger could not have glanced to her right and formed the image she described, based on the undeniable photographic evidence showing the two halves of the heavily mutilated body laid out, facing up, inches from the sidewalk.

In addition, Bersinger mentions seeing children riding their bicycles on the street. It is inconceivable that they would not have noticed such a prominently posed bisected corpse, which the police established had been placed on Norton Avenue around 6:30 a.m. Witnesses in the neighborhood claimed they walked by the location as late as 8:30 a.m. and didn’t see anything. With all of the foot traffic common to Norton Avenue, how could someone fail to have noticed the startling figure displayed along the sidewalk until nearly 11:00 a.m.?

Because the body wasn’t there.

At 11:05 a.m., Bersinger’s phone call came into the complaint line of the LAPD. At 11:07 a.m., a “390 down”—police scanner code for “intoxicated individual passed out”—was dispatched to radio unit 34, officers Frank Perkins and Wayne Fitzgerald. At 11:09 a.m., Perkins and Fitzgerald arrived at Norton Avenue. Five minutes later, at approximately 11:14 a.m., car 34 radioed LAPD’s University Division, requesting backup. Homicide Bureau Chief Jack Donohoe was immediately notified. At 11:18 a.m., officers S. J. Lambert and J. W. Haskins of University Division arrived at the scene, followed quickly by Sergeant Marty J. Wynn of Homicide Division and a succession of sergeants, lieutenants, police photographers, Scientific Investigative Unit investigators, and crime lab technicians.

At 11:30 a.m., Harry Hansen and Finis Brown, the two homicide detectives who would lead the investigation, arrived at the packed crime scene. Newspaper reporters and photographers had already assembled en masse, stepping around the body while taking notes and photos, preparing to breathlessly report in print and on the radio every detail of the scene as well as Hansen and Brown’s first observations.

But as close as reporters got to the body, as much information as they pried out of the police, investigators were able to hold back three crucial details. The police would use these pieces of information in questioning potential suspects, as only the killer would know the answer. Two of those questions and their answers were eventually revealed, but one remained a secret, and does so to this day. The police referred to it as “the Key Question.”

A 1971 LA Times article about Harry Hansen states, “Within this group of questions was one that was relevant yet so bizarre and remote that its answer was beyond even a wild guess, but obvious to the killer. Police called it ‘the Key Question,’ and will admit only that it deals with some fact about the condition, appearance, or attitude of Elizabeth’s Short’s body at the time it was discovered.” Hansen goes on to deny that a rumored marking on her body or any rearrangement of her organs was the basis of the Key Question. “Hansen asked the question of approximately 500 people. Not one ever responded correctly. Not one even came close.”

Though he never revealed any more details, Hansen left a very important clue in his description of the Key Question. His choice of words, “at the time it was discovered” is the giveaway. Reporters and photographers stood inches from the body. They witnessed and catalogued every aspect of its condition, appearance, or attitude. If there was something about the condition, appearance, or attitude of the victim’s body that only the killer would have known, then some aspect of the positioning of the body shifted between “the discovery” and the moment reporters first arrived.

Betty Bersinger discovered the body, but she did not touch it. At 11:09 a.m., officers Fitzgerald and Perkins arrived and were alone at the crime scene. At 11:18 a.m., the second set of officers, S. J. Lambert and J. W. Haskins, arrived. What happened in the crucial nine-minute gap between the arrival of the first and second set of officers that would alter the condition, appearance, or attitude of the body?

The answer lies with Betty Bersinger. At 103 years old, the woman who first stepped into the story of the Black Dahlia murder would be the last to leave it, having outlived every other participant. Until her death in October 2023, she lived in a retirement home and retained all her faculties. In one last interview, conducted with the author, she provided details of what she experienced that morning that she had never divulged before. When asked why she had never shared this information, her response was simple: “Nobody ever asked.”

Excerpted from Sisters in Death by Eli Frankel. Published by Citadel. Copyright © 2025. All rights reserved.