“A stranger arrives, makes love to everyone and then leaves,” said Pier Paolo Pasolini to Terence Stamp, outlining the plot of his 1968 classic Theorem. “That’s your part.” Stamp exclaimed: “I can play that.” It was the role that the man was born to play and would play, with subtle variations, throughout his career.

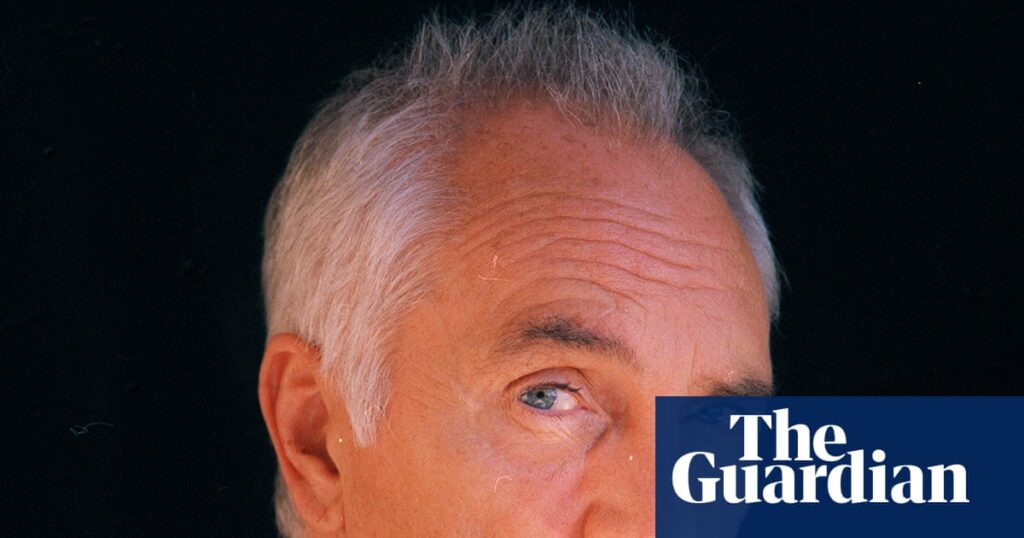

From his first appearance as the eerily beautiful sailor in 1962’s Billy Budd through to his last manifestation as “the silver-haired gentleman” in Edgar Wright’s Last Night in Soho, Stamp remained a brilliantly, mesmerisingly unknowable presence. He was the seductive dark prince of British cinema, an actor who carried an air of elegant mystery. “As a boy I always believed I could make myself invisible,” he once said. He showed up and made magic, but he never stuck around for as long as we wanted.

Stamp’s talent was timeless but he was a creature of the 60s, forged in the crucible of postwar social mobility and as much a poster boy for the era as his one-time flatmate Michael Caine. “Terry meets Julie, Waterloo station, every Friday night,” Ray Davies sang on the Kinks’s Waterloo Sunset and while he wasn’t necessarily singing about Stamp and Julie Christie – at least not consciously – the actors and the song have now become intertwined, part of a collective cultural fabric, to the point where that mental image of the two of them by the Thames is almost as much a part of Stamp’s showreel as his actual 60s pictures.

He was born in London’s East End, the son of a tugboat coalman who regarded acting with horror, and his rough-hewn swagger lent a crucial grit and danger to his refined matinee idol aesthetic. He gave a superb performance – full of seething chippy rage – in 1965’s The Collector, a role that won him the best actor prize at Cannes, made an excellent dastardly lover in Far from the Madding Crowd and whipped up a storm in Federico Fellini’s uproarious Toby Dammit. But he was always a more febrile movie actor than his compatriots – Caine, Sean Connery, Richard Harris, Peter O’Toole – and so his career proved more fragile and never truly bedded down.

“When the 60s ended, I almost did too,” he once said, ruefully acknowledging a decade-long slump that only came to an end when he was cast as General Zod in 1978’s Superman. In the subsequent years he played too many off-the-peg Brits – thuggish gangsters, evil businessmen – in subpar productions, although this only made his occasional great role feel all the more precious. Stamp was at his full-blooded best in Stephen Frears’s 80s crime drama The Hit, sparked briefly as the devil in The Company of Wolves and was fabulous as Bernadette in 1994’s Priscilla, Queen of the Desert.

But his great later role – and arguably the ultimate Stamp performance – was in The Limey, Steven Soderbergh’s 1999 revenge tale. Soderbergh cast him as Wilson, an ageing career criminal who haunts LA like a ghost. It’s a film that is implicitly about Stamp’s youth and age, beautifully folding the present-day drama in with scenes in Ken Loach’s Poor Cow to show what happened to the golden generation of swinging 60s London – and by implication, what happens to all of us.

after newsletter promotion

Somewhere along the way, wending his way up the coast to Big Sur, Stamp’s knackered criminal stops being a ghost and becomes a kind of living sculpture, a priceless piece of cinema history, returned for one last gig to seduce the world and set it spinning before heading off towards the sunset.