This article is part of “Innovations In: RSV,” an editorially independent special report that was produced with financial support from MSD, Sanofi and AstraZeneca.

Susan Green developed a stubborn cough in December 2023. It has never gone away.

Nearly two years after contracting respiratory syncytial virus, or RSV, Green, now aged 72, still suffers from chest congestion and a phlegmy cough. Because she coughs so much when lying down, she has to elevate the head of her bed in order to breathe easier and get a good night’s sleep.

On supporting science journalism

If you’re enjoying this article, consider supporting our award-winning journalism by subscribing. By purchasing a subscription you are helping to ensure the future of impactful stories about the discoveries and ideas shaping our world today.

While some of Green’s worst symptoms have eased, the virus has sapped her endurance, making it harder for her to exercise. The experience, she says, “has been life-changing.”

Most people contract RSV by their second birthday, with multiple reinfections throughout life. Although these bouts tend to be mild, with symptoms similar to the common cold, RSV can trigger severe disease in the very young, the very old and those who are immunocompromised.

RSV caused up to 6.5 million medical visits, 350,000 hospitalizations and 23,000 deaths from October 1, 2024, to May 3, 2025, a period that includes the typical RSV season, according to the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Two to three of every 100 babies under six months old are hospitalized for RSV, making it the most common cause of hospitalization in infants in the U.S.

Yet there is also good news about RSV. After decades of research and failed efforts, scientists have produced a bumper crop of game-changing RSV vaccines and immunizations to protect the most vulnerable people.

“It is a new era for RSV,” says Amesh Adalja, an infectious disease expert and senior scholar at the Johns Hopkins Center for Health Security.

In the past two years, the U.S. Food and Drug Administration has approved five medical products to prevent RSV: three vaccines for adults—including one for pregnant people that protects their newborns—and two preventive antibody treatments for infants. Of the latter, the most recent approval was in June.

“We now have an opportunity to dramatically reduce the impact of RSV on many, many families,” says Robert Hopkins, Jr., medical director of the National Foundation for Infectious Diseases.

RSV can inflame the lungs, causing them to secrete more mucus than usual. Newborns and frail older people often have a hard time coughing up the mucus, Hopkins says.

In children, mucus can become trapped in the bronchioles—some of the tiniest airways in the lungs—and prevent the lungs from exchanging oxygen and carbon dioxide, says James Campbell, vice chair of the committee on infectious diseases at the American Academy of Pediatrics. This condition, called bronchiolitis, can cause wheezing and is most dangerous in the first months of life, when newborns’ airways are extremely narrow. In the most serious cases, babies may need to go to the hospital to receive oxygen or require a mechanical ventilator to help them breathe.

In severe cases, RSV can lead to pneumonia, which occurs when the air sacs in the lungs become swollen and filled with fluid or pus.

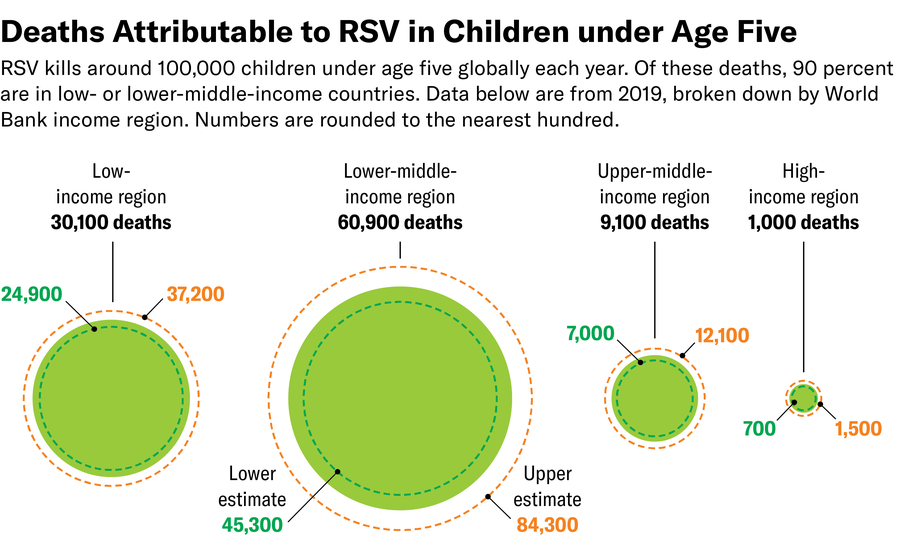

Worldwide, RSV is responsible for more than 3.6 million hospitalizations and about 100,000 deaths in children under age five each year, according to the World Health Organization. Most children who die from RSV live in low- and middle-income countries with limited access to hospital care.

An infection early in life can reverberate for years, increasing the risk of long-term wheezing, asthma and impaired lung function, research shows. In some children, “when you get infected with another respiratory virus, you start wheezing again,” explains Kristina Bryant, hospital epidemiologist at Norton Children’s Hospital in Louisville, Ky. “When the acute infection is over, you may not have seen the end of the trouble that this virus is going to cause.”

Protecting Older Adults

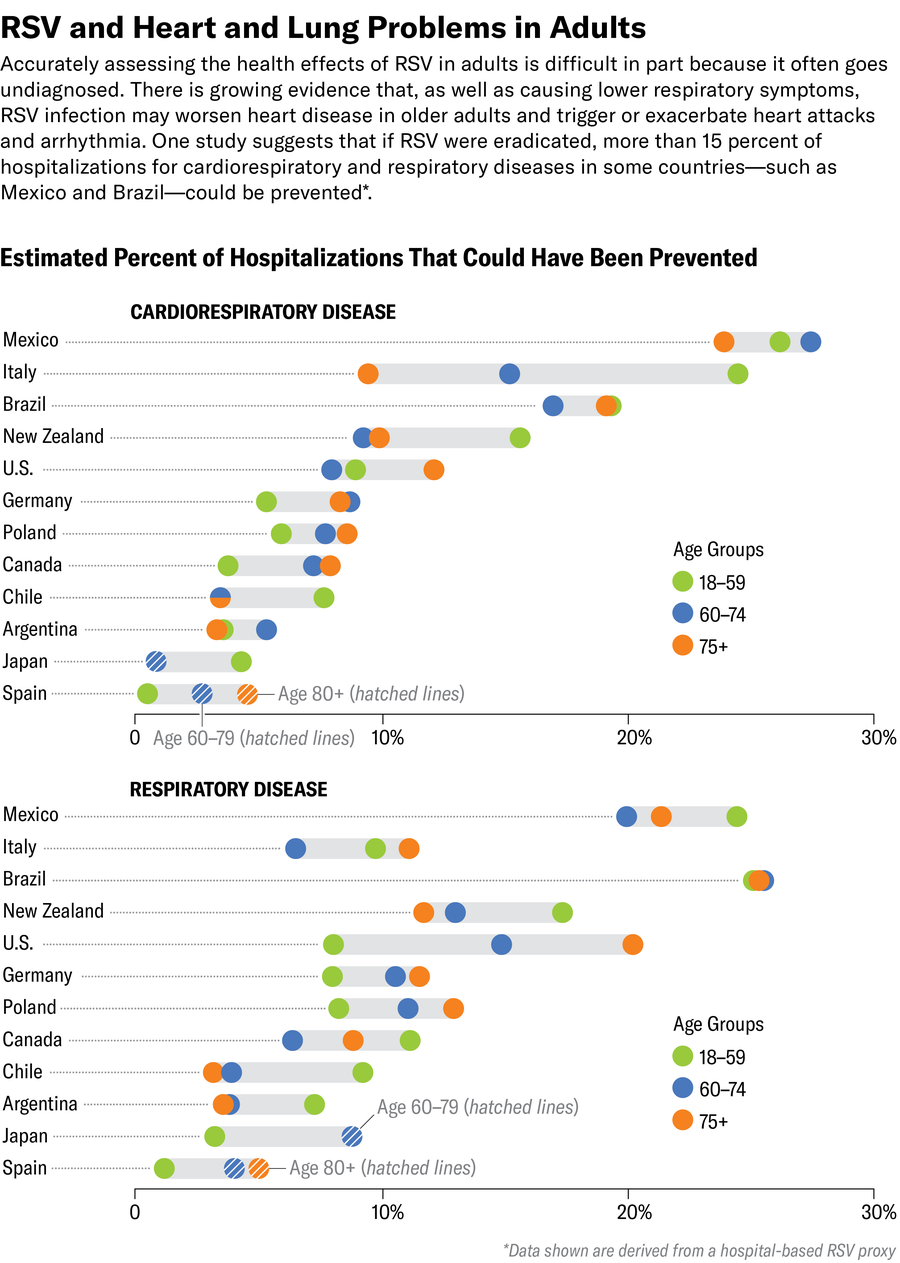

For decades, researchers assumed that RSV was largely a danger to babies. As doctors began testing more people for the virus, they discovered it is also a major driver of hospitalization in older adults.

Adults who are hospitalized with RSV have an increased risk of heart failure, abnormal heart rhythms, strokes and heart attacks, even months after the infection has passed. In a study of 2,210 adults age 50 or older who were hospitalized with RSV-caused pneumonia in a Colorado population between 2016 and 2023, 35 percent were admitted to the intensive care unit, and 9 percent died. In that study, people with dementia were the most likely to need intensive care.

Like many people, Green wasn’t familiar with RSV when she became sick. “At the time, I had not even heard of it,” says Green, who lives in Washington State.

But about a month after she first developed symptoms, a computed tomography (CT) scan found signs of damage in her lower lungs. Green was shaken when, after observing the lung damage, a doctor told her, “There’s nothing we can do, and you will have that cough for the rest of your life.”

Green has much less energy than before her RSV infection. She has always loved outdoor activities such as kayaking, and she used to paddle three to four times a week for miles. “I can’t do that now,” she says.

Before RSV, Green also participated in dragon boat races, a competitive sport in which crews of racers paddle to the beat of a drummer. She gave it up when she “found that I would go into a coughing fit, which was too distracting for the others on the boat,” Green says. “There are many more things I would be participating in, but I’m fearful of having the coughing flares that sound awful. People either think I’m contagious or have emphysema,” a chronic lung disease.

Green frequently takes over-the-counter medication to relieve chest congestion, especially if she’s planning to be active.

“I’ve advised everybody that I know” about RSV, Green says. “This is horrible stuff.”

RSV vaccines are critical, given the limited treatment options, Adalja says.

The best available treatment for RSV today involves primarily supportive care, such as helping patients breathe more easily. The antiviral medication currently available to treat RSV “has significant limitations and is really only used for severely immunocompromised patients,” though there is hope for better treatments on the horizon, he says.

Many health conditions increase the risk of a severe RSV infection, including an impaired immune system, heart disease or chronic lung disease, such as asthma. People who are socially disadvantaged, including racial and ethnic minority groups, are more likely to have risk factors for severe RSV disease.

This fall, Green hopes to receive one of the three RSV vaccines now available for older adults. The CDC recommends RSV vaccines for all adults aged 75 or older, as well as people aged 50 or older who have a high risk of a severe infection.

People who have had a diagnosed case of RSV can still benefit from vaccination, Adalja says.

The FDA approved the first two RSV vaccines for adults in May 2023 and a third in May 2024. The three adult vaccines on the market today include GSK’s Arexvy, Moderna’s mResvia and Pfizer’s Abrysvo, which is also approved for pregnant people.

The best time of year to be vaccinated is in late summer to early fall, before the virus begins circulating widely, according to the CDC. So far, people have only needed to be vaccinated against RSV once. Unlike the viruses that cause influenza or COVID, RSV doesn’t change much from year to year, Hopkins says. The CDC notes that it may update RSV vaccine recommendations depending on the results of ongoing studies ..

Although the vaccines are relatively new, a growing number of studies suggest they are already keeping people out of the hospital.

For example, an observational study published in June in the Lancet Infectious Diseases found that older veterans who received RSV shots were about 80 percent less likely to develop an infection, visit an emergency department or urgent care or be hospitalized compared with unvaccinated veterans.

Steven Weitzen sees vaccines as an important way to stay healthy.

Weitzen, who received a heart transplant on his 60th birthday in 2019, signed up for an RSV vaccine as soon as it was available. The medications that prevent his body from rejecting his new heart also suppress his immune system, leaving him extremely vulnerable to infections. He has been vaccinated against flu, COVID and other viruses that could threaten his health.

“There’s no vaccine I haven’t received,” says Weitzen, who lives in Randolph, N.J.

Because infectious diseases such as RSV pose a serious threat to transplant patients, Weitzen takes several precautions to stay healthy, including avoiding indoor spaces, such as gyms, restaurants and stores. He exercises either at home or outside, for example, and only sees his grandchildren and 91-year-old father outdoors. “I haven’t been able to give my dad a hug in years,” Weitzen says.

Protecting Children

Infants today can be protected from RSV in one of two ways—by vaccinating their moms before delivery or by giving them a shot of lab-grown antibodies shortly after birth.

In August 2023 the FDA approved the Abrysvo vaccine for use during pregnancy.

Vaccinating pregnant people against RSV during weeks 32 to 36 of pregnancy allows them to pass protective antibodies to the fetus through the placenta. A clinical trial found that vaccinating women during this period of pregnancy reduced the risk of severe RSV infections by 91 percent in the first three months of life compared with placebo.

Elizabeth Gross said she was thrilled that an RSV vaccine was available in time for her second pregnancy in 2024. Her son, who was born full-term and healthy, “hasn’t so much as had a cold since then.”

Gross had hemorrhaged heavily while delivering her first child in 2020. Her daughter, who was born prematurely, needed specialized medical attention. The experience made her acutely aware of the many dangers that newborns face and made her determined to do everything possible to protect her children, including vaccinating them against disease.

Having a medically fragile child who skirted tragedy several times “made us realize just how mortal we are and how science can be a saving grace,” says Gross, aged 36, who lives near Harrisburg, Pa.

When people aren’t vaccinated during pregnancy, their babies can still be protected after birth.

Infants can now receive injections of monoclonal antibodies—immune cells made in a lab rather than inside the human body—to protect them during their first RSV season.

The FDA approved the first such treatment, nirsevimab, made by Sanofi and AstraZeneca, in July 2023. A second monoclonal antibody treatment, Merck’s clesrovimab, was approved in June 2025. The antibodies can protect babies for at least five months, the typical length of an RSV season and the most dangerous time for infants, Hopkins says.

The monoclonal antibodies resemble a vaccine because they’re delivered as a shot. But unlike a vaccine, which stimulates the body to make its own antibodies, monoclonal antibodies deliver ready-made antibodies directly to the baby, Hopkins says.

The CDC estimates that 57 percent of infants born between April 2024 and March 2025 received either the maternal RSV vaccine or nirsevimab, and early studies suggest that these prevention strategies are already protecting babies.

“RSV is a frequent cause of newborn death in lots of countries,” says Kevin Ault, a professor of obstetrics and gynecology at the Western Michigan University Homer Stryker M.D. School of Medicine. Newly available interventions to prevent RSV could be “a real game changer as far as infant health worldwide” goes.

Vaccine Uptake

Uptake of adult vaccines tends to be much lower than childhood vaccines. Only about half of adults receive the flu shot each year, for example. Only about one third of eligible adults have been vaccinated against shingles.

As of April, 48 percent of adults aged 75 and older report receiving an RSV vaccine, with an additional 8 percent saying they will definitely get the shot in the future, according to the CDC. Among adults 60 to 74 with a high-risk condition, 38 percent report getting an RSV vaccine, with an additional 10 percent saying they plan to do so.

Vaccination rates are particularly low among some populations.

According to an analysis published in July, only one in 10 people served by the Veterans Health Administration had received an RSV shot by the end of 2024 for that viral season, even though veterans can receive the vaccines for free.

Researchers found that veterans who saw their health providers in person were more likely to receive the vaccine compared with those who made virtual visits. Vaccination rates were lowest among veterans who lived in rural areas, those aged 60 to 74 and smokers. Veterans without stable housing also were less likely to be vaccinated against RSV.

Racial and ethnic minority communities—who tend to have higher rates of chronic illness and more exposure to pollution—stand to benefit the most from RSV vaccination, says Juanita Mora, an allergist and immunologist, and board member of the American Lung Association. RSV hospitalization rates among Indigenous infants and toddlers are up to 10 times higher than the rate of the general population.

Yet RSV vaccination rates among Black and Hispanic individuals tend to be lower than those of the overall population in the U.S., partly because of a lack of insurance and access to care, Mora reports. A study that examined vaccination rates across the U.S. from July 2023 to June 2024 showed that 21 percent of the overall Medicare population was vaccinated. Among Hispanic people using Medicare, 7 percent received an RSV vaccine, along with 13 percent of Black people.

Mora, who is Mexican-American, says she tries to help Spanish-speaking families learn about RSV vaccination through social media and by visiting churches.

“I’ve seen the devastation that RSV can cause,” Mora says. “I think we still need to do more work when it comes to reaching those pregnant women.”

Valinda Jones, aged 71, who received a kidney transplant 16 years ago, says she hopes to get an RSV vaccine soon. Like Weitzen, Jones takes antirejection drugs that suppress her immune system. Jones has developed diabetes and heart rhythm problems since receiving the transplant, putting her at even higher risk from an RSV infection.

Jones, who is Black, says she can understand why many communities of color are reluctant to be among the first to receive a new type of vaccine. “Racism is real in health care,” Jones says. “Those communities have been marginalized and been taken advantage of…. Research demonstrates that there’s medical mistrust for really good, sound reasons.”

But Jones, a nurse who formerly worked as a quality manager for a kidney transplant program in a hospital, decided she wants to get the vaccine after watching her 77-year-old cousin become very sick with RSV.

As nurses, “our job is to educate people and empower them to make informed decisions and not try to coerce them one way or the other,” says Jones, who lives in the Greater Houston area and is pursuing a doctoral degree in nursing. “Ultimately, that’s your decision to get vaccinated or not.”