Nature has interviewed a multitude of physicists this year in celebration of the 100th birthday of quantum mechanics. Although many of them disagree wildly about how the century-old theory describes reality, something they seem to agree on is their favourite science-fiction films. Throughout several interviews, two were consistently highlighted for their depictions of science: 2014’s Interstellar and 2006’s The Prestige — both of which were directed and co-written by Christopher Nolan.

Happy birthday quantum mechanics! I got a ticket to the ultimate physics party

Nolan, who won an Academy Award for directing 2023’s Oppenheimer — a deep dive into the scientists behind the atomic bomb — credits his initial interest in physics to being introduced to science fiction as a child by watching the Star Wars films and television programmes such as Carl Sagan’s Cosmos: A Personal Voyage. “It was something that stuck with me, and it was something I applied very much to films like Interstellar,” he told online interview website The Talks in 2023. “It showed us the dramatic possibilities, that looking at the universe from a scientific perspective could be very, very engaging.”

Nolan declined to be interviewed for this story; we can assume that’s because he’s busy filming The Odyssey, a retelling of the Greek epic, slated for a 17 July 2026 release. Here, we delve into why physicists love his work. (Warning: spoilers ahead.)

The Prestige (2006)

The plot: Robert Angier (played by Hugh Jackman) and Alfred Borden (Christian Bale) are rival magicians in late 1890s London, who each dazzle audiences with a ‘teleportation’ trick. Borden pulls his off by hiding the fact that he has an identical twin, with whom he shares the same identity. Angier, however, gets help from famed scientist Nicola Tesla (David Bowie) to build a teleportation machine, which creates a new version of Angier every time he does the trick.

The science of Oppenheimer: meet the Oscar-winning movie’s specialist advisers

“It’s a brilliant movie,” says Barry Luokkala, physicist and author of the 2013 book Exploring Science through Science Fiction, who also teaches a course with the same name at Carnegie Mellon University in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania.

Luokkala, who in his class shows a clip from the film, says this for a few reasons: first, it picks up on the fascination with illusions and magic that he experienced as a child. Second, it takes an ambitious, fictional leap from what we know about the actual science of teleportation, and third, it’s an “interesting character study to show Hugh Jackman’s character, who is a brilliant showman, next to Christian Bale, who is not, and how highly competitive they are”.

It’s a story that also lingers. “The Prestige lives rent-free in my brain: it’s like a steampunk representation of science that we still don’t know,” adds Rithya Kunnawalkam Elayavalli, who studies space-time evolution of fundamental particles at Vanderbilt University in Nashville, Tennessee. “We know how to teleport information … but it’s not a representation of science that we know.”

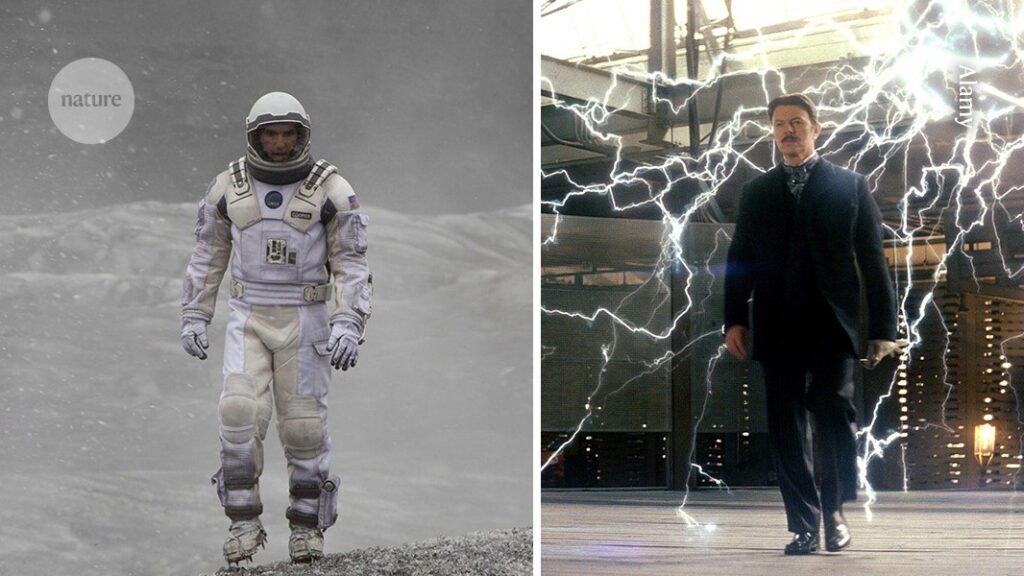

Interstellar (2014)

The plot: Joseph Cooper (played by Matthew McConaughey) is a retired NASA scientist tapped to pilot a mission through a wormhole to save humanity by colonizing a habitable planet near a black hole named Gargantua. Cooper later learns that those on the mission were never meant to return, and realizes that the presence of the wormhole was caused by actions of scientists in the future, including himself.

“It’s real science, and it’s based on real physical phenomena pushed to the limit,” says Claudia de Rham, a theoretical physicist at Imperial College London, who also made a podcast about the film.

Why Oppenheimer has important lessons for scientists today

The idea of space, time and parallel universes presented in the movie are fascinating, says Kai Liu, a materials physicist at Georgetown University in Washington DC. So is the concept “that you can go back in time and see the Universe with a different light”, he adds.

Interstellar also inspired physicists’ group-watch events. Kunnawalkam Elayavalli was a PhD student at Rutgers University in New Brunswick, New Jersey, when the film came out, and saw it with her fellow students. “We took up a whole row in the movie theatre,” she says. “We were the most annoying people to watch that movie with.” Manuel Calderón de la Barca Sanchez, who studies heavy-ion collisions at Brookhaven National Laboratory in New York, told Nature that he, too, organized a group outing of scientists to see it.