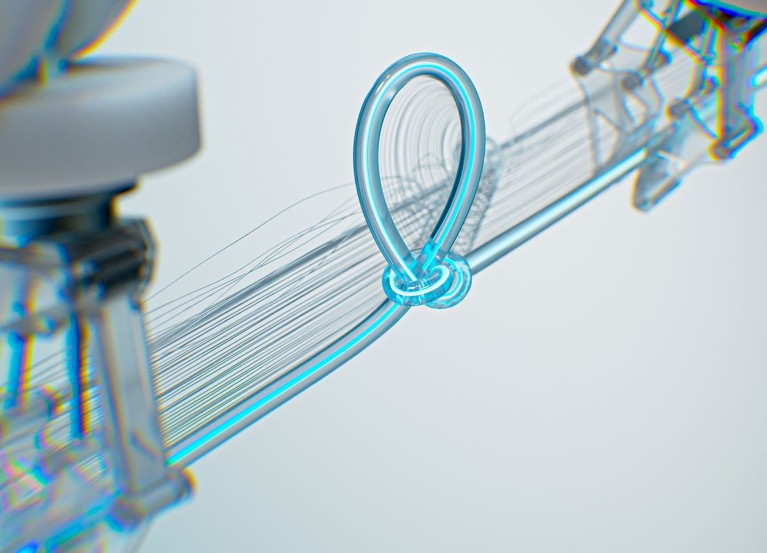

Surgeons could use pre-tied slipknots to precisely control the tension of stitches. Credit: Addictive Stock Creatives/Alamy

Inserting easy-to-release slipknots into surgical thread could help surgeons to tie perfect sutures — tight enough to help heal a wound but not so tight that they damage tissue.

Researchers worked out how to precisely control a knot’s geometry and friction so that they could ‘program’ it to open when tugged on with a specific force.

This allows a surgeon — or a robot — stitching up a wound to pull a suture closed with just the right amount of force, tugging the free end of the knotted thread and stopping when the knot unfurls. Getting the force right is important: stitches that are too tight or too loose can lead to complications.

In simulated operations described in Nature on 26 November1, the slipknot technique allowed inexperienced surgeons to perform sutures as well as their experienced peers. When used in rats, slipknot-aided colon surgery led to blood flow being restored faster, fewer leaks and less scar tissue than is usually the case for conventional stitches.

Stitches made simple

Surgeons usually gauge how much tension is in stitches by look and feel — a skill that takes years to learn and remains variable even in experts.

Adding a slipknot to the thread creates “a kind of built-in mechanical fuse” that limits how much force can be transmitted to the tissue, says Tiefeng Li, a researcher in mechanics and robotics at Zhejiang University in Hangzhou, China, who co-led the team of mathematicians, mechanics researchers and clinicians behind the research. “The surgeon only needs to follow a very simple rule: pull until it unfurls, then you know you are at the intended force.”

A simple slipknot comes undone if the thread is pulled hard enough. Credit: Chaoyang Zhao, Kaihang Zhang, Tiefeng Li

The type of knot used consists of a loop that unravels when one end of the thread is pulled. Although such knots seem simple, the mechanics inside them are complex, says Li. “When a slipknot opens, the thread bends, twists, slides, and rubs against itself, and the geometry of the knot changes very quickly,” he says.