In the spring of 2022 the U.S. space community selected its top priority for the nation’s next decade of science and exploration: a mission to Uranus, the gassy, bluish planet only seen up close during a brief spacecraft flyby in 1986. More than 2.6 billion kilometers from Earth at its nearest approach, Uranus still beckons with what it could reveal about the solar system’s early history—and the overwhelming numbers of Uranus-sized worlds that astronomers have spied around other stars. Now President Donald Trump’s proposed cuts to NASA could push those discoveries further away than ever—not by directly canceling the mission but by abandoning the fuel needed to pull it off.

The technology in question, known as radioisotope power systems (RPS), is an often overlooked element of NASA’s budget that involves turning nuclear fuel into usable electricity. More like a battery than a full-scale reactor, RPS devices attach directly to spacecraft to power them into the deepest, darkest reaches of the solar system, where sunlight is too sparse to use. It’s a critical technology that has enabled two dozen NASA missions, from the iconic Voyagers 1 and 2 now traversing interstellar space to the Perseverance and Curiosity rovers presently operating on Mars.

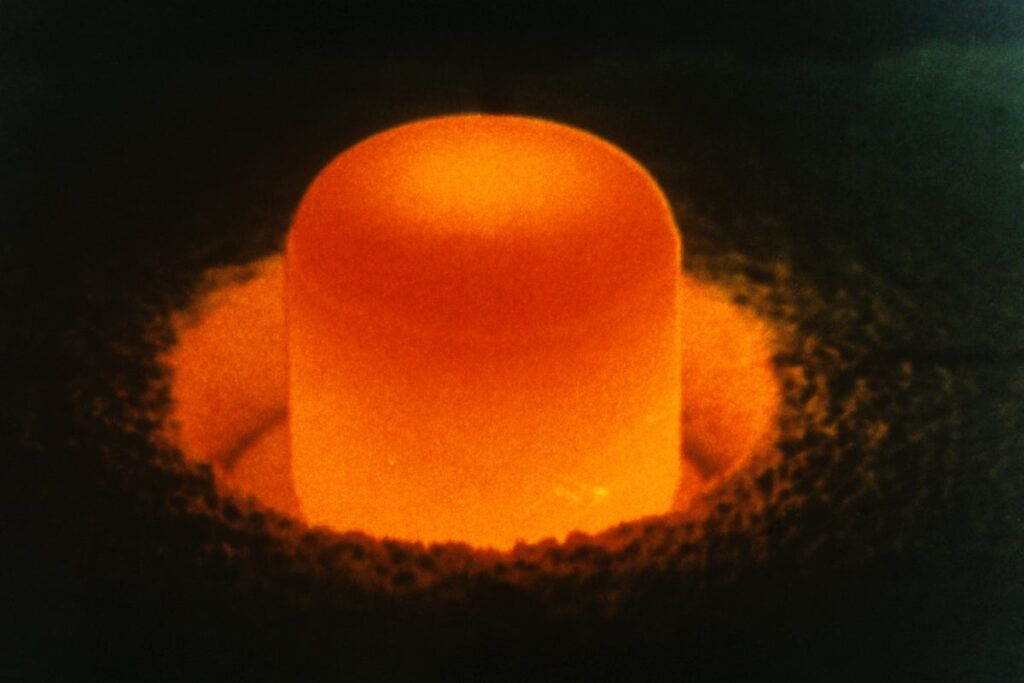

But RPS is expensive, costing NASA about $175 million in 2024 alone. That’s largely because of the costs of sourcing and refining plutonium 238, the chemically toxic, vanishingly scarce and difficult to work with radioactive material at the heart of all U.S. RPS. The Fiscal Year 2026 President’s Budget Request (PBR) released this spring suggests shutting down the program by 2029. That’s just long enough to use RPS tech on NASA’s upcoming Dragonfly mission, a nuclear-powered dual-quadcopter drone to explore Saturn’s frigid moon Titan. After that, without RPS, no further U.S. missions to the outer solar system would be possible for the foreseeable future.

On supporting science journalism

If you’re enjoying this article, consider supporting our award-winning journalism by subscribing. By purchasing a subscription you are helping to ensure the future of impactful stories about the discoveries and ideas shaping our world today.

“It was an oversight,” says Amanda Hendrix, director of the Planetary Science Institute, who has led science efforts on RPS-enabled NASA missions such as Cassini at Saturn and Galileo at Jupiter. “It’s really like the left hand wasn’t talking to the right hand when the PBR was put together.”

Throughout its 400-odd pages, the PBR repeatedly acknowledges the importance of planning for the nation’s next generation of planetary science missions and even proposes funding NASA’s planetary science division better than any other part of the space agency’s science operations, which it seeks to cut by half. But “to achieve cost savings,” it states, 2028 should be the last year of funding for RPS, and “given budget constraints and the reduced pipeline of new planetary science missions,” the proposed budget provides no funding after 2026 for work by the Department of Energy (DOE) that supports RPS.

Indeed, NASA’s missions to the outer solar system are infrequent because of their long durations and the laborious engineering required for a spacecraft to withstand cold, inhospitable conditions so far from home. But what these missions lack in frequency, they make up for in discovery: some of the most tantalizing and potentially habitable environments beyond Earth are thought to exist there, in vast oceans of icy moons once thought to be wastelands. One such environment lurks on Saturn’s Enceladus, which was ranked as the nation’s second-highest priority after Uranus in the U.S.’s 2022 Planetary Science and Astrobiology Decadal Survey.

“The outer solar system is kind of the last frontier,” says Alex Hayes, a planetary scientist at Cornell University, who chaired the Decadal Survey panel that selected Enceladus. “You think you know how something works until you send a spacecraft there to explore it, and then you realize that you had no idea how it worked.”

Unlike solar power systems—relatively “off-the-shelf” tech that can be used on a per-mission basis—RPS requires a continuous production pipeline that’s vulnerable to disruption. NASA’s program operates through the DOE, with the space agency purchasing DOE services to source, purify and encapsulate the plutonium 238 fuel, as well as to assemble and test the resulting RPS devices. The most common kind of RPS, a radioisotope thermoelectric generator, converts the thermal energy released from plutonium 238’s natural decay to as much as 110 watts of electrical power. Any excess heat helps keep the spacecraft and its instruments warm enough to function.

Establishing the RPS pipeline took around three decades, and the program’s roots lie in the bygone cold war era of heavy U.S. investment in nuclear technology and infrastructure. Preparing the radioactive fuel alone takes the work of multiple DOE facilities scattered across the country: Oak Ridge National Laboratory produces the plutonium oxide, then Los Alamos National Laboratory forms it into usable pellets, which are finally stockpiled at Idaho National Laboratory. Funding cuts would throw this pipeline into disarray and cause an exodus of experienced workers, Hendrix says. Restoring that expertise and capability, she adds, would require billions of dollars and a few decades more.

“These decisions are made by people that don’t fully understand the implications,” says Ryan P. Russell, an aerospace engineer at the University of Texas at Austin. “Technologically, [RPS] is on the critical path to superiority in space, whether that’s military, civilian or industrial applications.”

Russell emphasizes that RPS isn’t just critical for exploring Uranus, Enceladus and other destinations in the outer solar system—it’s also a likely fundamental pillar of the administration’s space priorities, such as developing a sustained human presence on the moon and sending astronauts to Mars. While both destinations are relatively close to the sun, the Red Planet’s global dust storms can bury solar panels, and the moon’s two-week-long lunar nights are cold enough to test the mettle of even the best batteries. The latter situation informed the reasoning that drove NASA’s acting administrator Sean Duffy’s directive last week to fast-track a lunar nuclear reactor.

Abandoning smaller-scale nuclear options such as RPS while aiming for a full-scale reactor is “like trying to build a house without a two-by-four,” Russell says. “If you don’t have the basic building blocks, you’re not gonna get very far.”

Another initiative reliant on RPS, NASA confirmed in a statement e-mailed to Scientific American, is the beleaguered Mars Sample Return (MSR) program that the U.S. agency has been jointly pursuing with the European Space Agency. While the White House has proposed nixing MSR, scientists and politicians view bringing Martian samples back to Earth as a key milestone in the modern-day space race against China.

Meanwhile other nations are pursuing or preserving their own RPS capabilities, with Europe’s sights set on americium 241, a radioisotope with a five-times-longer half-life but a five-times-weaker energy output than plutonium 238. Russia has used RPS for decades, and China and India are also developing homegrown versions of the technology.

Notably, despite the administration’s push for commercial partners to take up costly space functions such as rocket launches, RPS is unlikely to find much support in the private sector. “Dealing with [this sort of] nuclear material—that’s not something a company is going to do,” Russell says.

Going forward, the planetary science community hopes to convince Congress that RPS is “critical and foundational,” Hendrix says. The Outer Planets Assessment Group (OPAG), which was chartered by and provides independent input to NASA, expressed its concerns to the space agency in findings from a June meeting, writing that the decision would have “dire implications” for future solar system exploration. White papers prepared by representatives of the Johns Hopkins University Applied Physics Laboratory and NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory, Goddard Space Flight Center and Glenn Research Center conveyed similar sentiments, noting that nine of the 15 existing and future missions recommended in the latest Decadal Survey use RPS.

In short, “you’re just hamstringing your ability to do certain mission configurations and also to get out to and past Saturn if you shut down RPS,” Hayes says. “You can’t argue that scientific prioritization was part of [the White House’s] decision process.”

Although both the House and Senate have released drafts of the 2026 appropriations bill that preserve top-line funding for NASA, neither explicitly mentions RPS. That means the program would fall under NASA’s “discretionary spending,” a category that scientists and legal experts alike say would be more easily manipulated by a presidential administration looking to enforce its political agenda. In other words, without a clear, direct callout for RPS from congressional appropriators, the Trump administration’s plan to shut down the program could more easily come to pass. Hendrix consequently hopes that Congress will add language explicitly funding RPS in its final budget.

“There is a strong interest from Congress in the need for a powerful, deep-space energy source,” says a congressional staffer who is familiar with the NASA budget and was granted anonymity to discuss these issues freely. But “I don’t know that members have quite honed in on [RPS] yet because the worry is so much about [Trump’s] intent to cancel a lot of future planetary missions.”

Fundamentally, political support for outer solar system missions is a moot point without corresponding support for the ability to get there, explains University of Oregon planetary physicist and OPAG co-chair Carol Paty. The decision to shut down RPS “seems like a simple line item,” she says. But the implications are “deeply troubling and concerning. If there are not big missions to drive the community, to drive exploration, to drive training the next generation, where does that leave us?”