August 29, 2025

4 min read

Voting Integrity Messages Fight Misinformation in the Lab. But What about the Real World?

Telling people exactly how voting security works helps defeat election misinformation, experiments suggest. But outside experts question how well that works in the real world

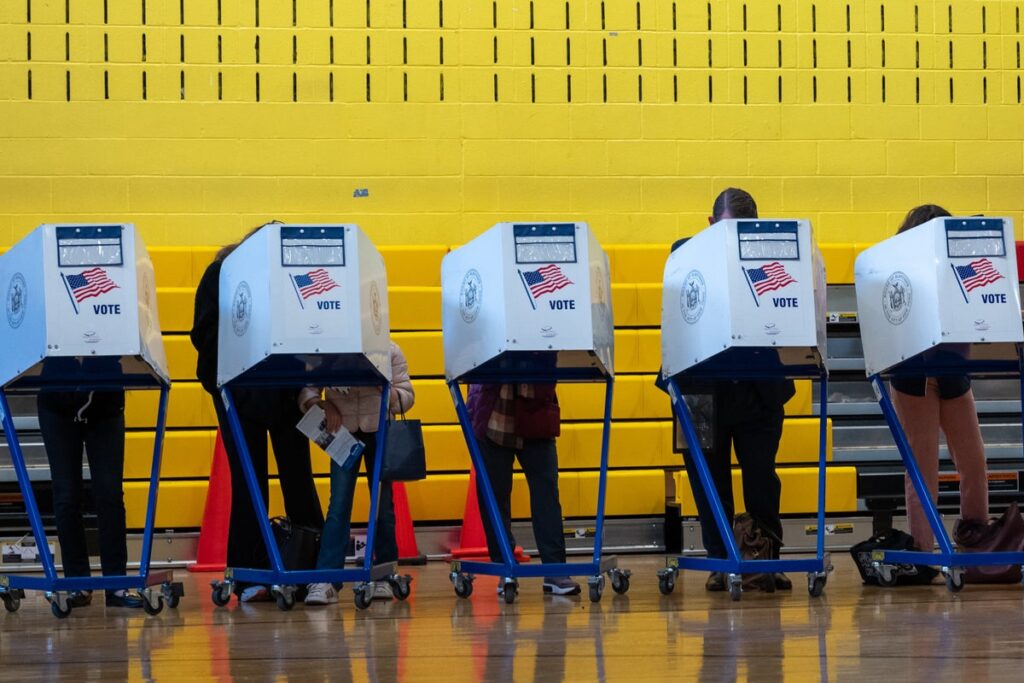

People cast their ballots on November 5, 2024 in New York City.

Wang Fan/China News Service/VCG/Getty Images

Safeguards keep fake ballots from being counted. Election officials regularly update voter lists. Voting machine software undergoes rigorous testing.

Telling voters such simple facts helps combat election misinformation, suggests a Science Advances study released on Friday. In the investigation, researchers performed messaging experiments with voters in the U.S. before the nation’s 2022 midterm elections and in Brazil after its presidential election that same year. With false claims of faked election results having figured into the January 6, 2021, mob assault on the U.S. Capitol and reelected U.S. president Donald Trump having made false claims about mail-in ballots and voting machines in August 2025, combating election falsehoods matters very much, the new study’s authors say.

“Around the world, we’ve seen attacks on election integrity, and it’s become clear that defending democracy requires debunking or effectively countering that misinformation,” says study co-author Brian Fogarty, a political scientist at the University of Notre Dame. What he and his colleagues found most effective was “genuinely novel information,” he says—such as details on exactly how voting security is ensured at the polls and in the counting of votes.

On supporting science journalism

If you’re enjoying this article, consider supporting our award-winning journalism by subscribing. By purchasing a subscription you are helping to ensure the future of impactful stories about the discoveries and ideas shaping our world today.

“The facts actually matter,” says psychology professor Gordon Pennycook of Cornell University, who was not a co-author of the study. “This is a very strong set of experiments, and I think the conclusion is very important: the best way to help guard people against misinformation is to provide accurate countervailing information.”

While Pennycook and other outside experts applaud the experiments as excellent research, however, they question their relevance in real elections. In the U.S. and Brazil, these experts note, voters are immersed in misinformation from talk radio, television personalities and, in the case of the U.S., even the country’s current president—and this fouls the information environment in which straightforward messages about election security can be delivered to them.

“We know people are misinformed. Can just one message in a sea of misinformation offset a diet of misinformation on social media,” and cable television, asks communications scholar Nathan Walter of Northwestern University, who was not part of the study. “Eating one protein shake doesn’t counter all the cheeseburgers you had.”

The study consisted of three experiments. The first two, which respectively included nearly 3,800 respondents in the U.S. and more than 2,900 in Brazil, tested attacks on voting integrity from political leaders of losing parties against “prebunking” information about how votes are secured that were preceded by warnings about conspiracy theories. As a control measure, some participants heard messages with information that was entirely unrelated to voting. Prebunking worked in both the U.S. and Brazil, and it was particularly effective among those most skeptical of election security and had a more lasting effect. Notably, the U.S. voting security information was taken from the (now deleted) “Rumor vs. Reality” section of the website of the U.S. Department of Homeland Security’s Cybersecurity & Infrastructure Security Agency.

The third experiment of 2,000 participants from the first experiment tested prebunking messages with and without the added conspiracy forewarnings. Somewhat surprisingly, the prebunking messages without the forewarnings about conspiracy theories proved most effective in countering misinformation, the study showed. Beliefs in false statements dropped from 19.5 percent in the control group to 12.3 percent in the forewarning group and to 10.6 percent among the participants who received simple explanations without forewarnings.

With the 2026 U.S. midterms ahead, voting groups, civil society organizations and journalists can take the study’s results as pointers to better showing people the lengthy steps taken to ensure that voting fraud is unbelievably rare in elections, writes Natália Bueno of Emory University in a companion article published in Science Advances.

“What seems to matter is this novel factual information is provided in the prebunking message, which is helping people understand how elections are secure,” Fogarty says. “We think these are encouraging findings with important implications for how to communicate with the public about election integrity going forward.” While the Trump administration has removed the DHS webpage with facts about election integrity that was used in one of the experiments, the study authors suggest voting rights groups could turn to the National Association of State Election Directors or National Conference of State Legislatures for similar prebunking explanations.

The U.S. federal government can no longer be considered a good-faith player in ensuring fair elections, however, says cognitive scientist Stephan Lewandowsky of the University of Bristol in England, pointing to the Trump administration’s embrace of 2020 false election claims. That makes even the most scientific prebunking look less useful as a tool for stabilizing democracy, warns Lewandowsky, who wasn’t involved in the new study. “The U.S. is now best characterized as an emerging autocracy with a very tenuous hold on democracy and lawfulness,” he adds.

It’s Time to Stand Up for Science

If you enjoyed this article, I’d like to ask for your support. Scientific American has served as an advocate for science and industry for 180 years, and right now may be the most critical moment in that two-century history.

I’ve been a Scientific American subscriber since I was 12 years old, and it helped shape the way I look at the world. SciAm always educates and delights me, and inspires a sense of awe for our vast, beautiful universe. I hope it does that for you, too.

If you subscribe to Scientific American, you help ensure that our coverage is centered on meaningful research and discovery; that we have the resources to report on the decisions that threaten labs across the U.S.; and that we support both budding and working scientists at a time when the value of science itself too often goes unrecognized.

In return, you get essential news, captivating podcasts, brilliant infographics, can’t-miss newsletters, must-watch videos, challenging games, and the science world’s best writing and reporting. You can even gift someone a subscription.

There has never been a more important time for us to stand up and show why science matters. I hope you’ll support us in that mission.