Metamorphosis: A Natural and Human History Oren Harman Basic Books (2025)

“Metamorphosis is wild,” marvels historian Oren Harman. A caterpillar completely dissolves inside its chrysalis, before reconstructing itself in the shape of a butterfly. The ‘immortal jellyfish’ (Turritopsis dohrnii) reverts from its mature, floating form into a polyp that dwells on the ocean bed when threatened, only to eventually turn back into a mature jellyfish again — never dying of old age.

Survival of the nicest: have we got evolution the wrong way round?

How such weird natural phenomena strike at the core of our understanding of biology is the focus of Harman’s beautiful book, Metamorphosis. The author uses the life stories of four scientists to argue that studies of metamorphosis — drastic changes in the body plan of an organism after birth — have been key to our understanding of the mechanisms of genetic inheritance, organismal development and evolution. It is a sweeping biography that is also part biology textbook, part cultural human history and part personal odyssey.

Harman begins in the 1600s, when philosopher Aristotle’s influence on popular theories was still prevalent and science and magic co-existed in the minds of scholars. “In reports of the highest caliber, sightings of new planets lay side by side with sightings of unicorns and dogs who could bark in French,” he notes. Many people still adhered to Aristotle’s theory that spontaneous generation — the miraculous formation of a living organism from dead material — accounted for metamorphoses.

It was against this backdrop that naturalist Maria Sibylla Merian travelled to South America in 1699 to document the life cycles of insects. According to Aristotle, most insects are ‘imperfect’ animals — born in a state that is completely different from their adult form. Driven by her obsession with metamorphosis, Merian published an illustrated book on the insects of Suriname, which remains a classic for its demonstration of caterpillar–butterfly life cycles.

As Harman shows, the work of naturalists in the seventeenth century led to an understanding that, rather than appearing through spontaneous generation, animals arise from fertilized eggs. Later, studies of butterflies developing in their chrysalises contributed crucial insights to the debate on whether an organism builds itself from scratch, as we now know to be the case, or whether the adult form exists inside the egg and simply grows larger.

Biology as history

Next, Harman turns to zoologist Ernst Haeckel, a nineteenth-century adopter of Darwin’s theory of natural selection. Haeckel viewed it as ridiculous to expect that living organisms could be reduced to simply ‘cold’ physical forces, as his university professors thought. Nor did he take to the romanticism of the natural philosophers, who thought that vital forces animated living creatures.

From egg to animal: retracing an embryo’s first steps

Instead, Haeckel saw biology as a historical science and argued that the ways in which species develop are intimately tied to their evolution over eons. For example, the human embryo changes shape as it develops: from a single cell to a mass of cells, then a body that temporarily has a tail and gills, followed by webbed fingers that later separate as the embryo takes on its mature form. To Haeckel, “Nothing made more clear how we humans had once been amoebas, sea squirts, fish, amphibians, then four-legged mammals.”

Haeckel dubbed this concept the biogenetic law and argued that it accounted for the apparent tendency of animals to become increasingly complex as they evolved. This tendency has been disproven as a law, but is sometimes still used as a rule of thumb. It is known by biologists today as ontogeny recapitulates phylogeny.

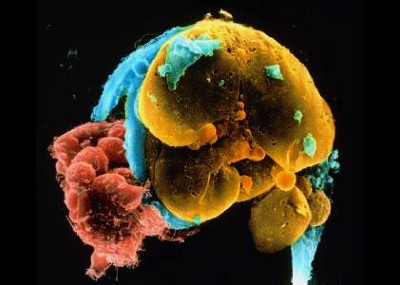

A dragonfly transitioning to its adult form.Credit: Education Images/UIG/Getty

Harman argues that metamorphosis is related to this concept, albeit tangentially, because the rate at which organisms metamorphose from a fertilized egg into their mature form can be explained by the biogenetic law. Haeckel emerges as an early forefather of the field that would come to be dubbed ‘evo-devo’.

The author also notes Haeckel’s tarnished legacy. He promoted theories of race that were related to his biogenetic law, which some historians have argued contributed to the rise of the Third Reich in Germany. Haeckel insisted on the supremacy of “civilized” Europeans and argued that, by flipping the lens of his biogenetic law, it was possible to predict how successful various groups of people would be — if development reveals secrets of the deep past, then it might also uncover aspects of the future of humanity.