November 18, 2025

4 min read

Heart Rate Irregularity Sounds Bad, but Here’s Why You Want a Bit of It

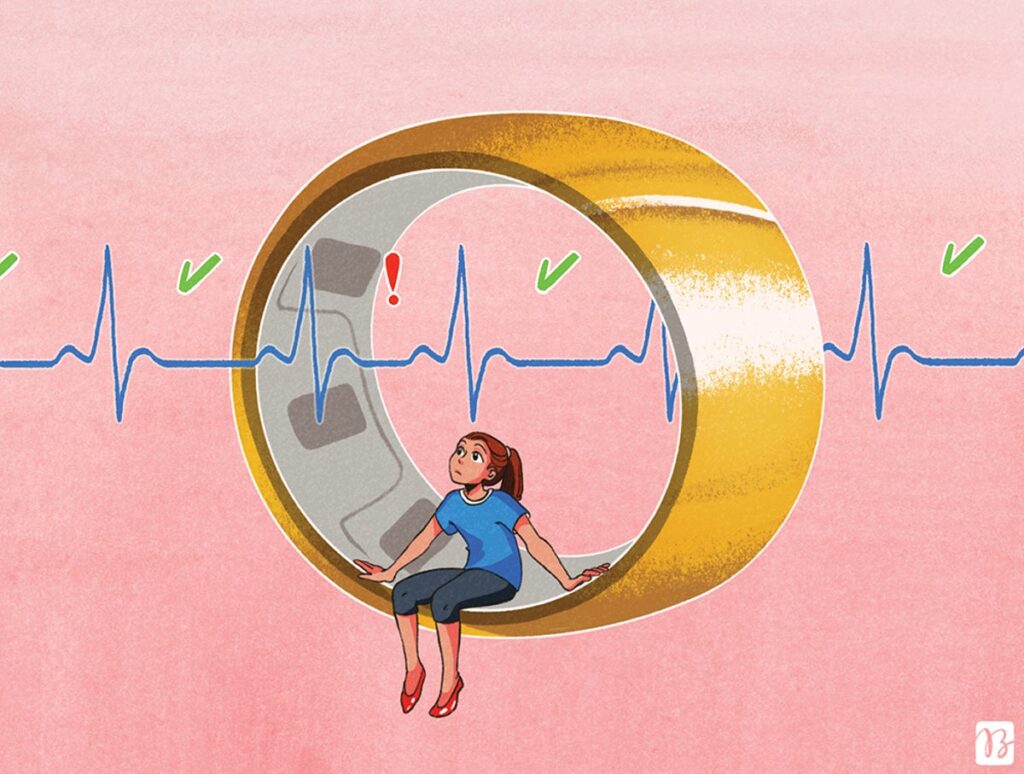

Milliseconds of variability, now detected by fitness watches, can improve well-being

Earlier this year I got an Oura ring to track the state of my health. Soon I was obsessing over my sleep and activity scores. The reports were generally positive except for one: heart rate variability, or HRV. That’s a measure of how much the time between heartbeats changes. Every morning, in bright red, my ring’s app singled out HRV and told me: “Pay attention.”

That didn’t sound good, although I had no idea why. Before wearable fitness watches, rings and bracelets became so common and started including HRV as a data point, I had never heard of it. Even among heart doctors, its use has been limited. “I don’t think HRV is used in day-to-day clinical medical practice,” says Bryan Wilner, an electrophysiologist at the Baptist Health Miami Cardiac and Vascular Institute. “But it’s gained a lot more popularity in regular consumers with these noninvasive monitors.”

Suddenly, we are all paying attention to HRV. And as reams of data are collected from hundreds of thousands of people like me, the measure has the potential to become a far more significant tool for diagnosis and therapy, although it isn’t there yet.

On supporting science journalism

If you’re enjoying this article, consider supporting our award-winning journalism by subscribing. By purchasing a subscription you are helping to ensure the future of impactful stories about the discoveries and ideas shaping our world today.

The average person’s heart rate is between 60 and 100 beats per minute when they’re at rest, but it fluctuates all day long. Standing up after lying down changes your heart rate, as does jogging or fielding stressful questions at work. The time between beats changes, too, and that’s what HRV captures. Unlike arrhythmias, which are potentially dangerous disruptions in the heart’s electrical activity, HRV measures the very slight variation in periods—a matter of milliseconds—between consecutive heartbeats, tracked over a few minutes or longer.

“There is no specific [HRV] number for what’s bad, what’s good.” —Attila Roka, electrophysiologist

Both heart rate and HRV reflect the differing effects of the two branches of the autonomic nervous system. The sympathetic nervous system, colloquially known as “fight or flight,” increases heart rate; the parasympathetic, or “rest and digest,” slows it down. Generally, the lower a person’s heart rate, the higher their HRV. A high HRV indicates a body that adapts to stressors and can recover more quickly. It’s a sign of a balanced autonomic nervous system and a higher level of cardiovascular fitness. Low HRV signals the opposite—that the body is less able to adjust to the ups and downs of life. Stress, anxiety, high blood pressure, inadequate sleep, dehydration and new medicines are among the many things that can lower HRV. Disease can reduce it, too. In people recovering from heart attacks or living with heart failure, low HRV is associated with a higher risk of death and further illness. “HRV is a window into how the autonomic nervous system is interacting with our heart,” Wilner says. Oura states on its app that it flags HRV because it is a sign of stress and recovery.

“There is no specific number for what’s bad, what’s good,” says Attila Roka, an electrophysiologist at the CHI Health Clinic Heart Institute and an assistant professor at Creighton University in Omaha. Anywhere from roughly 20 to 70 milliseconds is considered within normal range. The measure is highly individual, although it generally goes down with age. Mine hovered around an unusual 14 for weeks, and that’s why my ring alerted me.

An electrocardiogram is the gold standard for measuring HRV. Cutting-edge pacemakers and defibrillators monitor it, too, and experts are investigating the use of HRV with heart disease patients to predict the onset of atrial fibrillation (Afib) in time to prevent it, says Pamela Mason, chief of cardiac electrophysiology at UVA Health in Virginia. Afib is an irregular, rapid heart rhythm that can lead to blood clots and other problems. Physicians also use Holter monitors, small devices that patients wear on their chests for a few days, to capture a full picture of cardiac activity, including HRV.

Devices like Apple watches and Oura rings work by looking at pulse fluctuations rather than electrical heart signals. Few studies have examined how accurate these devices are. But what’s more important for the average person, experts say, is the relative change over time. “You need to get a baseline HRV,” Wilner says. “HRV is most powerful when you’re measuring it over several weeks and can see a graphic trend on how it’s being affected by everything that’s going on in your life.”

HRV might one day be used to assess mental health. “If you’re in a constant fight-or-flight kind of state mentally, you’re going to lose heart rate variability,” Mason says. Conditions such as depression and bipolar disorder are likely to be associated with dysregulated nervous system activity. Even among people without medical or psychiatric disorders, studies have found a link between decreasing parasympathetic activity and emotional upset, suggesting HRV tracks psychological states.

Low HRV, in relatively healthy people, does have some remedies. “The best way to improve heart rate variability is exercise,” Mason says, “and it’s going to need to be more strenuous than gentle walks.” Pick up the pace to pick up your HRV. Drinking more fluids—water is good—also helps.

For people like me, Mason’s advice is to not obsess. Instead consider what you could do to take better care of yourself. Prodded by red HRV alerts, I drank more water and consumed less caffeine, went to bed earlier, and engaged in vigorous exercise more regularly. Since then, my HRV has been higher than 30! Not that I’m obsessing over it.

This article was made possible by the support of Yakult and produced independently by Scientific American’s board of editors.