After a summer lull in U.S. cases of avian influenza in both poultry and dairy cattle—and no human infections reported in the country since February—the virus is back.

Bird flu’s return threatens major economic losses for the U.S. agricultural system and raises a small but real risk of a human pandemic. Scientists expected bird flu to return. It was highly unlikely that, following three full years of infecting U.S. poultry and making the surprising leap into cows, the virus would simply disappear.

The currently circulating bird flu subtype H5N1 is here to stay. “We’ve resigned to this phase,” says Seema Lakdawala, a virologist at Emory University. “Now we have to figure out what we’re doing next.”

On supporting science journalism

If you’re enjoying this article, consider supporting our award-winning journalism by subscribing. By purchasing a subscription you are helping to ensure the future of impactful stories about the discoveries and ideas shaping our world today.

Scientific American spoke with Lakdawala and other experts about why the virus has returned, what threats it poses, and what people need to know.

How prevalent is bird flu right now?

In poultry, bird flu is on the rise: according to the U.S. Department of Agriculture, 50 flocks of commercial and backyard poultry in the country had confirmed avian influenza infections in October. Farmers cull all birds on infected premises to reduce the virus’s spread, and this month, more than three million animals have been killed to date.

Carol Cardona, a poultry veterinarian at the University of Minnesota, says she’s worried by the fact that the state’s board of animal health has already reported 20 flocks with confirmed infections since the beginning of September. “We’re definitely having a bad year here in Minnesota,” Cardona says.

The outbreak in dairy cattle, which was identified in March 2024, is also still ongoing. The virus is more difficult to track in cattle because, unlike poultry, the animals tend not to die after they are infected. The infection reduces cows’ milk production, however.

Keith Poulsen, director of the Wisconsin Veterinary Diagnostic Laboratory and a large animal veterinarian at the University of Wisconsin, notes that several states, including California and Idaho, are seeing ongoing infections in cattle—but that he knows this only because of informal conversations with colleagues. Meanwhile last month the USDA confirmed Nebraska’s first known dairy infection, suggesting the virus is still spreading among herds. But in general, reporting of infections in dairy cattle is slow and disorganized. “We don’t have enough information to know what our risk is, and that’s a pretty precarious position,” Poulsen says. “We don’t know what we don’t know.”

Why is bird flu on the rise again now?

This month’s nationwide poultry infection numbers represent a stark increase from those of the summer months: June, July and August each saw fewer than one million poultry culled to combat bird flu. But scientists expected that there would be an increase in the disease’s prevalence in poultry as autumn arrived for two reasons. First, hotter temperatures seem to quell the virus, and the weather is getting cooler. “The virus survives better in the cold weather,” says Rocio Crespo, a poultry veterinarian at North Carolina State University. “So we are going to have more outbreaks than we have seen in the summer.” Second, avian influenza is widespread among wild birds, and many of those birds migrate south to warmer climates, carrying the virus with them.

Together, those two factors mean that bird flu cases in poultry have settled into an apparent annual cycle since the current outbreak was first identified in early 2022, with losses generally being lowest in June, July, and August and highest in December, January, February and March.

How is the government shutdown affecting the response to bird flu?

The federal government has been shut down since October 1, when the new fiscal year began with no funding measures covering standard operations. Across the government, only those employees deemed “mission critical” at federal agencies continue to work.

Press personnel for the USDA’s Animal and Plant Health Inspection Service, which maintains the agency’s avian influenza dashboards, did not respond to Scientific American’s requests for details about the office’s staffing during the shutdown. Cardona says that she knows of agency staffers in Minnesota and nearby states who are continuing to work on bird flu, and the dashboards for poultry, dairy and wild bird cases all show updates dating to the month of October.

Much of the U.S. response to avian influenza was always at the level of individual states rather than that of the federal government, which means that surveillance and control plans are still being implemented, Poulsen says. “Surveillance is working,” he says. “We’re finding positives, and we’re dealing with them appropriately.”

Where he sees a key weakness now is in communication between the states, which the USDA facilitated via meetings that are now canceled, Poulsen says. He also says that the agency lacks the veterinarians and support staff to confront the reality of the current animal disease landscape in North America, which includes not just avian influenza but also New World screwworm infestation, foot-and-mouth disease and African swine fever.

How does bird flu relate to seasonal flu in humans?

The seasonal rise in avian influenza in poultry coincides with the beginning of human influenza season, raising scientists’ fears that these flu viruses could mingle, with potentially devastating consequences.

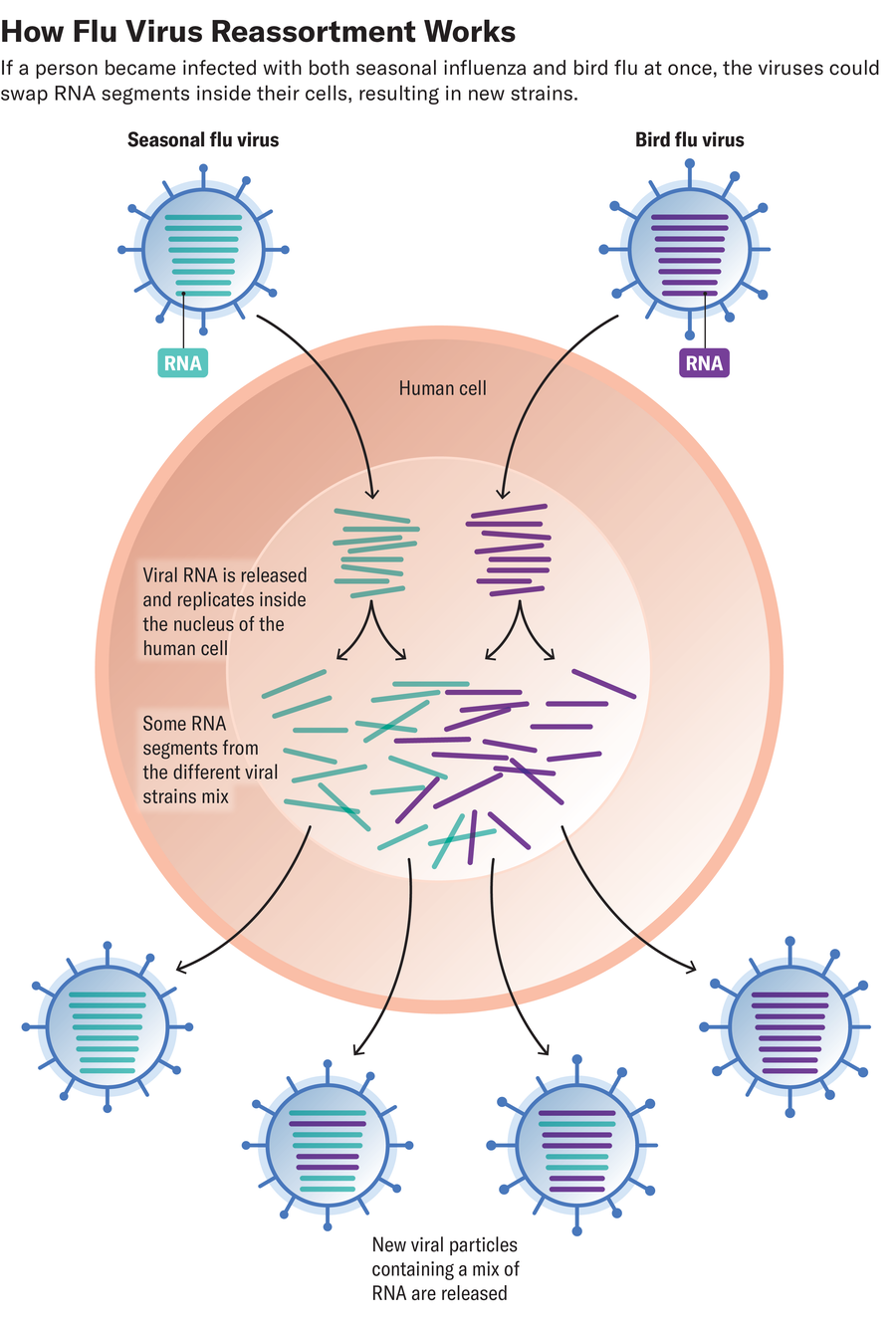

Influenza viruses are prone to swapping their genetic material with each other—a process called reassortment. That’s one major reason that, every year, scientists develop a new flu vaccine to target the specific strains they expect to circulate most. If a bird flu virus gains a seasonal flu’s ability to easily infect humans, the result could be a novel pandemic disease—one to which people would have no existing immunity and that, scientists fear, would have an even higher mortality rate than COVID did during its initial emergence.

Cow udders may offer one venue for such a hybrid virus to develop. But scientists also worry about coinfection in humans—events in which the same person is infected with both avian influenza and a seasonal flu virus at the same time.

Fortunately, it would likely take many such human coinfections for a dangerous virus to emerge because flu reassortment is relatively rare in people, Lakdawala says. “Two viruses have to get inside of a single cell in your body of millions, billions of cells and replicate and make something new,” she says. Unfortunately, the more prevalent each virus is, the more likely such coinfections are, making the matched increase of bird flu and seasonal human flu dangerous.

What are the risks of bird flu?

Most people’s risk from the current strain of bird flu is quite low, experts emphasize. Although the CDC has reported 70 confirmed cases in humans, almost everyone who has been infected had direct contact with infected animals, and most cases have been mild. That’s in contrast to previous outbreaks of other bird flu strains that, estimates suggest, killed as many as half of the people who were infected.

For now, Poulsen is much more worried about how the nation’s poultry and dairy agriculture systems will withstand the virus continuing to afflict the animals these industries rely on. He fears, for example, another spike in egg prices that will be similar to what the U.S. saw in late 2024 and early 2025. So far, milk prices have been more resilient to bird flu’s upheaval, but there’s no guarantee that will remain the case—particularly in an economic landscape that is now shaped by tariff-driven price increases.

“For the general public, they’re going to see more expensive food, or they might not be able to get food,” Poulsen says.

How can people stay safe from bird flu?

Although bird flu is not currently a high risk for most people, experts still recommend several measures to keep yourself and others safe from the virus:

People who regularly interact with animals that are susceptible to bird flu should be more cautious. If you keep backyard poultry, be aware of bird flu rates in your area and handle your birds only while wearing personal protective equipment (masks and gloves) and clothing that stays outside the house. Farmworkers should also wear protective gear and follow biosafety protocols, although scientists are realizing that these workers need better tools to keep themselves safe. “We have excellent personal protective equipment for individuals working in lab settings,” Crespo says. “But many of those do not work that well on the farm.” She’s heartened by a recent workshop held by the National Academy of Sciences to bridge this gap.

What are some of the big questions about bird flu right now?

This year Cardona is particularly interested in how the virus will evolve. She’s seeing evidence that avian influenza has been undergoing substantial reassortment in wild birds. Influenzas are identified by two surface proteins. The bird flu virus that is currently circulating is a subtype dubbed H5N1. But Cardona says she’s now hearing of cases of the subtype H5N2, as well as cases of H5N1 with differing gene compositions. “The virus is putting on its disguises,” she says. “That can change the way the virus behaves in an animal species.”

Crespo is focused on the experience of poultry farmers who desperately want to know how the virus is infiltrating their flocks despite the fact that they have employed a host of measures meant to protect the birds.

And Poulsen wonders how the Trump administration’s work in shrinking the federal government and attacking science will shape the U.S. response to bird flu—and our overall public health system.

But as worried as these experts are by the return of bird flu and the evolving challenges it poses, they’re still in the fight. “One advantage we have over this virus is: we are smarter than it is,” Cardona says. “We really need to start using our brains and figure out how to get to a more manageable state.”