– – –

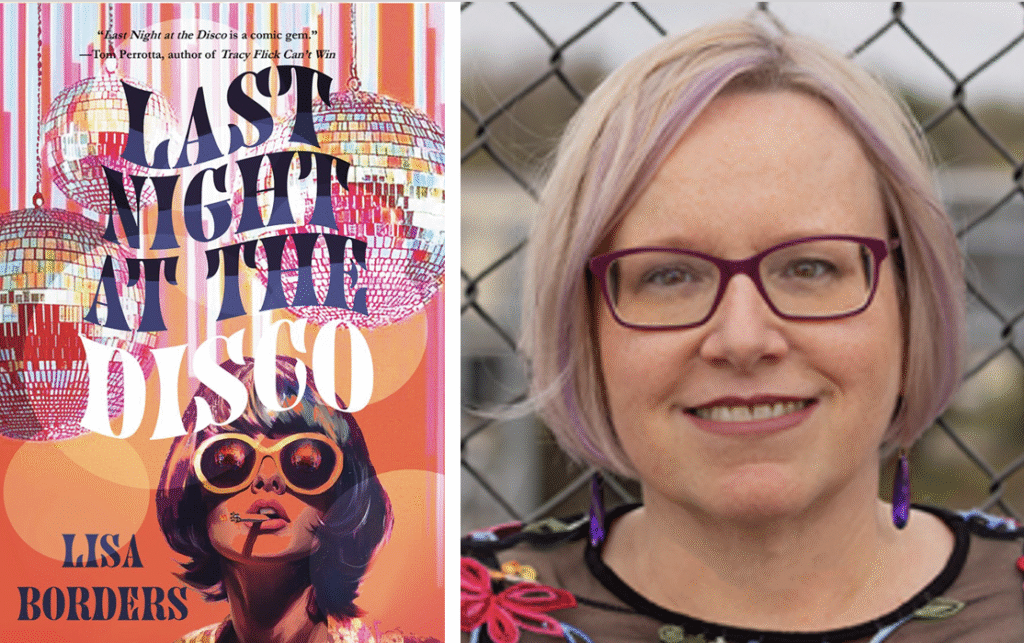

In 1977, a New Jersey junior high school teacher who spends her weekends at Studio 54 discovers two musicians who become among the most influential artists of the 1980s. Decades later, having burned bridges with them both, she tells her story in hopes of securing her rightful place in rock ’n’ roll history. Written as an email to former Rolling Stone publisher Jann Wenner, frequent Tendency contributor Lisa Borders’s Last Night at the Disco has been praised as “hilarious” by Publishers Weekly, adding, “Readers will be hooked by this tragicomic romp.” Today, we’re thrilled to share an excerpt from the book.

– – –

Johnny met me outside the club. He had glitter on his eyelids and below his brows, but was otherwise dressed unremarkably: plain black T-shirt, jeans, tooled leather boots. An ordinary costume that somehow accentuated his beauty. We headed inside and nabbed the last open table.

Before I divulge the contents of my first in-depth conversation with Johnny Engel, let me de-romanticize the CBGB myths that some rock magazines—certainly not yours!—have promulgated. Bear in mind that I was no fussbudget, no cleaning-obsessed Jersey casalinga like my mother; I’d lived in the Village, waitressed there, read my poetry there. But CBGB was filthy even by Village standards of that era. The table we sat at was wet with beer, dripping off the sides; cigarette ashes mixed in with the sluice. My seat cushion was so grimy-looking that I worried my dress would be permanently stained. The bathroom—I can’t even talk about the bathroom. Suffice it to say that, after a used hypodermic needle crunched under my heel, after I peered into a feces-stained toilet whose seat was broken off and propped unhelpfully against the wall, I learned just how much my bladder can endure in one night.

A braless waitress with an unflattering Toni Tennille bowl haircut came by and wiped a filthy-looking rag over the wet table, nearly hitting me with the slosh. She grudgingly took our orders: a beer for Johnny, a gin and tonic for me.

I broke the ice by asking where he was from originally, for Johnny’s accent was clearly not of the tri-state area.

“Michigan,” he said. “Small town, not too far from Detroit.”

“I haven’t lived anywhere besides New York and New Jersey,” I admitted. In college, I’d occasionally told my classmates that I’d lived in Paris when I was a child; it was true emotionally, if not literally. I should have lived in Paris. But I got the sense that wasn’t the tack to take with Johnny.

“I hadn’t lived anywhere besides Michigan up until last year,” he said. “For six years after high school, I worked an assembly line for GM. I wanted desperately to be a musician, gigged on weekends. But I knew I’d never make it the way I wanted if I stayed there.”

“That’s why most artists move to New York,” I said.

“Yeah, but the job I had was plum. Great salary. Amazing benefits. People thought I’d lost my mind to give it up.”

“What made you do it?”

“When I turned twenty-five, I realized time was running out. If I wanted to make it in rock, I couldn’t wait any longer. I had to try.” Johnny sighed. “The band I had in Michigan was glam, or at least, what passed for glam. I moved here to form the ultimate glam band, but the songs I wrote never quite fit that sound. And then last month, glam rock died.”

“Glam rock died?”

“Well, Marc Bolan died. It’s pretty much the same thing.”

The waitress put our drinks in front of us. I took a sip of mine, calculating how best to proceed. I knew nothing of glam rock, but I thought Johnny might enjoy introducing me to his world.

“I don’t know much about that kind of music,” I said. “Is the band we’re seeing tonight glam?”

Johnny laughed. “The Ramones—no. They’re not glam.” He took a swig of his beer. “But I find their music really exciting. I still love glam, but I kinda think this, what’s happening here”—he gestured widely with his arms, toward the grimy tables surrounding us, the emaciated junkie couple making out in the corner, the dingy stickers that covered the inside of the club’s walls—“is the future of music.”

“Interesting,” I said. This poor, deluded man! The future—a much more glamorous future!—was happening a train ride away, at Studio. As if to emphasize this point, a shirtless man who looked and smelled like he hadn’t showered in weeks slammed into our table, spilling our remaining drinks. Johnny stood up. He towered over the guy.

“Sorry, man,” the guy slurred, and darted back into the crowd. Johnny sat back down.

“The future?” I asked, raising a playful eyebrow.

He smiled and shrugged.

The waitress appeared with two more drinks. “You guys might want to stand when the band comes on,” she said.

Johnny thanked her, then looked at me. “I didn’t mean to monopolize the conversation. Tell me about yourself. How long have you been teaching?”

“This is my third year,” I said. “The teacher thing is temporary for me. I’m a poet. But I wasn’t making it financially, and had no choice but to give in to the bourgeoisie for a while.”

“Poet and teacher by day, tripping the light fantastic by night,” Johnny teased, and I laughed a little.

“You really must come to Studio with me next weekend,” I said. “It’s not as debauched as its reputation.”

“Oh, I don’t have a problem with debauchery,” Johnny said.

– – –

We got up from our table as the floor in front of the stage grew crowded. Four guys in jeans, T-shirts, nearly identical leather jackets and dark hair took the stage. The one on the left snarled and sneered; the lead singer hid behind his hair. Had no one taught them how to perform? Their songs were two-minute assaults, like dodging gunfire. Give me Donna Summer, I thought; give me The Village People. Give me joy and glamour any day over noise and filth. I repeated this like a mantra to myself as I steeled against the onslaught of the band’s noise.

Finally, at the point where I thought I would truly have to leave, the Ramones exited the stage.

“What did you think?” Johnny asked.

“It was… different,” I said. A guy to my right vomited all over the floor, nearly hitting my shoes. Johnny ushered me away.

“Not your thing at all, huh?” He smiled.

“No,” I said. “But I’ll come back if you’ll come to Studio with me next weekend.”

Johnny nodded. “Sure, I’ll try anything once.” O, the fantasies in that moment!

We left CBGB and found an all-night diner, where we had coffee and pie and talked some more. I’d dearly missed those kinds of nights in the Village: a new conquest, the excited late-night conversation. By the time we left the diner, it was nearly three a.m. The next train back to Jersey wasn’t until eight.

“You can stay over at my place, if you want,” he said.

O, did I want!

– – –

But my evening at Johnny’s ended up being a disappointment. We talked for a little while, sitting close on the sleeper couch in his tiny studio. I filled him in on Aura, on how she was bullied at school, grieving the loss of her father—though I kept to myself the special nature of my relationship with her father— and how I’d decided to be her mentor. I gave all my best signals, but he never put a hand on my thigh or leaned in for a kiss. By four a.m., he said he was exhausted, and gave me a T-shirt to sleep in. We lay side by side on the thin, hard mattress; it was quaint, nearly Amish. But how to get the Rumspringa started?

I’d never been in a situation like this with a man where he hadn’t tried something. What made Johnny so different, so courtly? Was the Midwest like that? Briefly I entertained the notion that he wasn’t attracted to me, but I quickly dismissed it. I’d never met a guy who wasn’t attracted to me. No, as I drifted off to sleep, I decided that he was simply a gentleman. Even my parents would love him!

– – –

Click to preorder Last Night at the Disco from bookshop.org.

– – –

From the novel Last Night at the Disco by Lisa Borders, releasing on October 7, 2025. Reprinted with permission of Regal House Publishing.