Places Charles Johnson’s drawings appeared when he was a young cartoonist:

- A catalog for a magic company

- Mimeographed church bulletins

- The Daily Egyptian

- The Southern Illinoisan

– – –

For more than forty years, Charles Johnson has been a fixture on the literary scene in Seattle, along with two other African American writers, both transplants: the late Octavia Butler and the late August Wilson. Like they did, Johnson has produced work his own way, avoiding the expectations that many would impose on a Black writer. This journey of distinction for Johnson began in 1982, with his second published novel, Oxherding Tale, a quasi–slave narrative and rogue’s narrative steeped in both Eastern and Western philosophy. Johnson has since published twenty books, and has received numerous accolades for his work, including the National Book Award for Fiction for his novel Middle Passage, a MacArthur Fellowship, and a Guggenheim Fellowship.

Born in 1948, Johnson grew up in the Chicago suburb of Evanston, home of Northwestern University. He first came to prominence as a political cartoonist and illustrator when he was still a teenager: At the age of fifteen, he was a student of cartoonist and mystery writer Lawrence Lariar’s. In 1969, he attended a lecture by Amiri Baraka, which inspired him to draw a collection of racial satire titled Black Humor, which was published by Johnson Publishing Company, the publisher of the widely read magazines Ebony and Jet. A second collection of political satire, Half-Past Nation-Time, was published by Aware Press in 1972. During this period, Johnson earned a BS degree in journalism at Southern Illinois University. He then went on to earn his MA in philosophy at the same university, while taking fiction-writing classes with the legendary John Gardner. In 1976, Johnson joined the faculty in the Department of English at the University of Washington, where he taught until his retirement in 2009.

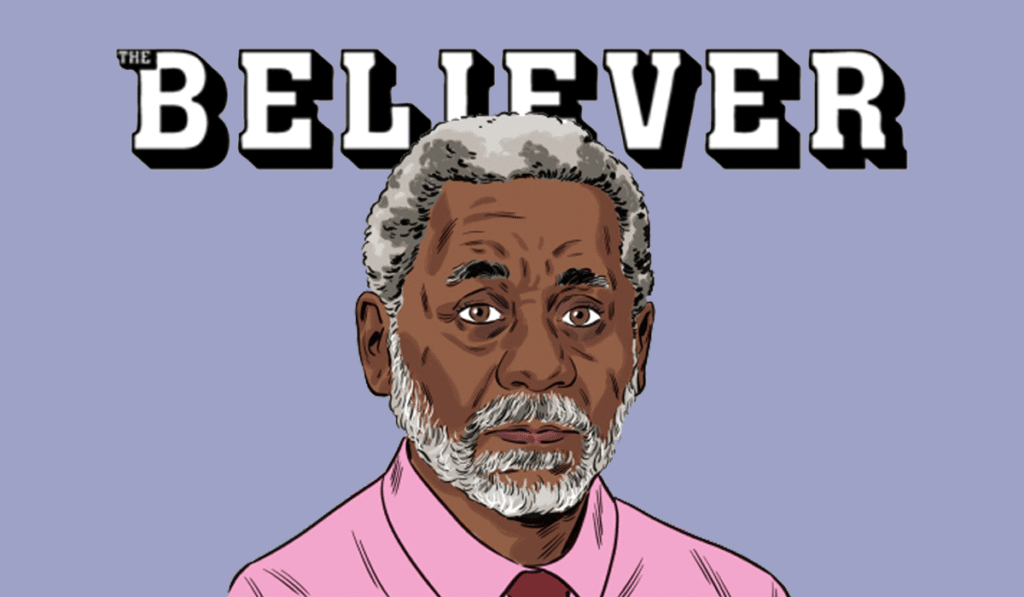

I sat down with Johnson on a mild afternoon at Third Place Books in Seattle’s Ravenna neighborhood, not far from Johnson’s home. To take advantage of the weather, we opted for an outside table, where we enjoyed good coffee, good food, and good conversation. Preferring the nickname Chuck, Johnson is confident but humble and soft-spoken; his eyes sparkled with intelligence. He keeps his hair in a short Afro, completely gray, with a well-groomed halter-like connected beard, also gray. As we spoke, I observed something of the scholar about him, in the way that his spectacles dangled against his chest from an elastic cord encircling his neck.

—Jeffery Renard Allen

– – –

I. TWIN TIGERS

THE BELIEVER: How do you define yourself as a writer?

CHARLES JOHNSON: I don’t call myself a writer. One of my books is titled I Call Myself an Artist.

BLVR: So you’re an artist?

CJ: Yes.

BLVR: I’m going to phrase the question differently. Would you call yourself an experimental writer in the usual sense of whatever that term means: someone seeking to innovate, break rules?

CJ: I’m a philosophical writer because my background is in philosophy. I work with different forms and genres to realize, I hope, fiction that is philosophically engaging and capable of transforming our perception in some way. As for experimentation, Clarence Major—he’s an experimental writer. And Ishmael Reed is as well. I’m not an experimental writer. The thing about it, too, is I started out as a cartoonist, as a visual artist and journalist. When I was in my teens, drawing was my first passion. Still is to a large extent. So I’ll say I’m an artist. Today I might be doing visual art. Tomorrow I might be doing literary art. Last night I got together with some old buddies for Wednesday-night martial arts class. We’ve been doing this since 1981, training together, every Wednesday night. As an artist, there are different ways to express myself.

BLVR: You see martial arts as a form of self-expression?

CJ: It is. Well, when I was young, back in my teens, it seemed to me reasonable that I needed to develop myself in three areas, to the best of my ability. One was mind, one was body, one was spirit. For mind, I chose philosophy, which seduced me when I was an eighteen-year-old undergraduate at Southern Illinois University. Even though I was a journalism major, I stayed on and got my master’s in philosophy. And then I kept going until I got my PhD in philosophy at Stony Brook University. So that was for mind. For body, I chose martial arts when I was nineteen. My first dojo was in Chicago, and was a little like a monastery. I began working out there, without knowing anything about the world of martial arts. It was a cult in the sense that the members of the school blindly followed the leader, but I didn’t know it. This was during the time of the Chicago Dojo Wars, as they were called. My school was in competition with another school, run by a flamboyant guy who called himself Count Dante. Count Dante. You’d see him sometimes in the martial arts magazines. [Laughing] I don’t know anything about his system or his style, but I do know that somebody from his school came by our school one night to invite us to participate in a tournament. He was really arrogant. He said, If you think you’re up to it, you can come try out in our tournament. Our master wasn’t there that night, but when he found out, he told all of us, Somebody comes in like that again, tell them to leave. They don’t leave, you go over here to the wall and take down a weapon. Give one to him and you take one. Now, these were traditional weapons, Chinese weapons, you know—spears and staffs and swords. And if he won’t leave, kill him. I’m thinking, What? He’s telling us to kill. He said killing was within our rights when somebody invaded our space and we gave them fair warning. It was a rough school. I thought some nights I’d die in there, but I stuck with it until I got my first promotion. Southern Illinois University was about six hours away. I couldn’t keep up at that dojo, but I continued with karate on campus. I went through three karate systems, you know, and then settled on Choy Lee Fut kung fu in 1981 when I went down to San Francisco to work on a Black PBS TV show called Up and Coming. Wherever I lived, I always looked for a school to train at.

When I came out this way, I discovered there were branches of the Choy Lee Fut school, one here in Seattle and one over in Bremerton. I was able to continue training here in Seattle until the one school here closed. After it closed, our teacher, Grandmaster Doc-Fai Wong, gave me and a buddy permission to start classes in Seattle. He gave us the name Twin Tigers. We taught for ten years. My buddy passed away a couple of years ago, but I still get together with a couple of old friends on Wednesday nights. We go through our empty-hand sets. Then we go through our weapons sets so we don’t forget them. Choy Lee Fut has over 130 sets because it combines three martial arts lineages, one from Mr. Choy, one from Mr. Lee, and another one from Chan Yuen-Woo, who taught Fut Gar. Choy Lee Fut is one of the old Shaolin monastery fighting systems.

So mind, body, and spirit. For spirit I chose Buddhadharma. Buddhadharma, for training and cultivating the spirit. I was born a cradle Christian, and I still am to a degree. But the Buddhadharma offered something that was good for me when I was young.

BLVR: How old were you when you were introduced to Buddhism?

CJ: Fourteen.

BLVR: And how did it happen?

CJ: Back then, my mother was an avid reader and a member of three book clubs. One of the books that came into the house was on yoga. I read a chapter on meditation and afterward I told myself, Let me see what this is like. For half an hour, I practiced the method of meditation described in this chapter. It was amazing. My consciousness changed during that half hour of focusing. I’d never done that before, and the experience affected me for life. It made me more conscious of the operations of my own mind and it also made me have more compassion for people around me, more empathy. I began to approach the study of Buddhism and other Eastern philosophies in a scholarly way and read everything I possibly could. As both an undergraduate and a graduate student, I took courses in Hinduism and Taoism.

BLVR: That was back in the ’60s?

CJ: Yes, back then, when there was all kinds of stuff floating around.

BLVR: You mean people like Alan Watts?

CJ: Yes, Alan Watts. And D. T. Suzuki was very important at the time because he interpreted Japanese Zen for a Western audience. He did it in a particular way to make it intellectually interesting to academics. Something I didn’t care for was what I call “fuzzy-bunny Buddhism,” the feel-good stuff. With Buddhism, you must get it right. It’s not any old thing you make it out to be.

Buddhism grows and evolves in every country it goes to. It has a particular flavor here in America, because Americans are very interested in politics and social justice. I think this is because we draw on Christianity’s emphasis on the social gospel about changing the world that had such an impact on Martin Luther King Jr. So there is that quality to the American Buddhist convert community.

BLVR: What impact has Buddhism had on literature in our country?

CJ: There’s very little written about the spiritual register in our literature, especially in fiction. Truth to tell, I don’t know American poetry as well as I know the fiction.

BLVR: In terms of my question, I’m thinking about two aspects of American fiction: the tradition that deals with spiritual questions, and the tradition that deals with philosophical questions. Would you say there’s also a lack in terms of philosophical fiction?

CJ: Going all the way back to the nineteenth century, Americans have been anti-intellectual, very suspicious of intellectuals, particularly of European intellectuals. The emphasis is on the common man, so to speak, right? You see that bias starting with Jefferson in the eighteenth century. The century that followed gave us philosophically interesting writers like Hawthorne, Melville, and Emerson the transcendentalist. But then something happens around the turn of the twentieth century with the rise of naturalism. Our writers become less philosophical and less focused on the spiritual register. Part of that has to do with the fact that naturalism in fiction is a subset of naturalism in science and sociology. Naturalism does not involve spiritual experiences. Of course, naturalism offers a deterministic view of the world. Biology, the environment, cause and effect—that’s all that really matters in the naturalistic orientation.

I think there’s more to human experience—and that experience is much, much larger than that.

In the twentieth century we don’t have much in the way of a spiritual/philosophical register in American fiction. William Gass, a trained and important philosopher, was one such writer. My former teacher John Gardner wasn’t a trained philosopher, but he explored ideas like Sartrean existentialism in his novel Grendel.

And then among Black writers I would say that Jean Toomer is philosophically interesting. Toomer was a follower of Gurdjieff. I wrote a preface for Toomer’s collection of aphorisms, Essentials, which was edited by the late Rudolph Byrd. Richard Wright is also interesting, even if he was largely a Marxist thinker.

BLVR: I would argue that Wright became an existentialist.

CJ: He was by the time he moved to France. Of course, over there he hung out with Sartre and Simone de Beauvoir. And he started getting into phenomenology. He owned a copy of a philosophical work by the founder of phenomenology, Edmund Husserl. I read, in fact, that he worked with it so much he had to get another cover for it because it was falling apart.

Ralph Ellison is also worthy of attention as a philosophical writer. In Invisible Man he addresses Marxism and existentialism, then plays on Freud, and so forth.

BLVR: Ellison seems to define the idea of race and racism as ultimately absurdist in an existentialist sense.

CJ: His novel is absurdist. Those writers to me are the ones I found to have a philosophical kind of register. Still not, though, a spiritual register. Not in Wright, not in Ellison. Only in Toomer.

– – –