You’ve Always Been This Way is a column written by Taylor Harris, a late-diagnosed neurodivergent woman and 1980s preschool dropout, who identifies every moment from her past that filled her with shame, and mutters, “Yep, that tracks. I see it all now.”

– – –

In another world, I write to you about special interests and solitude, of rumination and soft tees, of parenting and partnering with a nervous system born to be bubble-wrapped. In that world, I dissect memories and recast them here as alive and something like art. I hope to write you from that place soon. The world of niche and quirk and whimsy matters too. We deserve reels of Black men singing Natasha Bedingfield on tandem bikes and Taylor Townsend coming home to herself with a honey deuce and smile at the US Open.

That world exists, but feels like the thin layer of oxygen my middle school science teacher said sits trapped between ice and the freezing pond water below. A pocket of air as hope. We might breathe long enough to find the broken ice we’d fallen through. But I never understood how you could get close enough to suck in air without water soaking your lungs.

Today I don’t write from that layer of air. Or maybe I do. Perhaps this is breathing. Forgive me if you don’t find fancy writing or wit here. Find, instead, my sentences bland, my syntax as precise as my early cursive writing. Find my form lacking, but the words, at bone level, true or close to it.

– – –

Year after year and within those years, days, and within those days, hours—in small talk and emails and phone calls and doctor’s visits and playground socials—I have apologized. Hedged my words with more words. Hesitated. Deferred. Gone low in stature. Assumed I know less than most people.

It’s never about missed social cues or sarcasm for me, but I mask and move by pre-emptively making myself small. I sit myself down as the student, rarely the professor, who has so much to learn about this big and busy world of efficient doers. If our world looks like Richard Scarry’s, I’m constantly looking on from another page.

For forty years, I’ve buffered the friction of living in this world with a brain that generates and processes about 40 percent more information at rest, by defaulting to thirty-one linguistic flavors of “my bad.” The record sounds like:

You’re probably right. Let me research. Let me change. Fix myself. Pray. Let me despise my brain. I missed something critical. I should not speak or present myself until I am worthy or smart enough or just enough.

And that works well enough. Until there’s an issue of justice.

Even then, I tread on lily pads. I wait. I hold in my body a guttural fear of being wrong, along with a compensatory core belief that I can get to the bottom of things. Just clear my schedule, order some takeout, and put the kids to bed. I feel the need to be an expert before I comment on anything, because I could be wrong, and what’s worse than being wrong? This means I can publish a book about motherhood and genetics in 2022 and still slink back from the conversation when the topic is Motherhood and Genetics in 2022. Eventually, my need to speak up slips through the tangles of doubt, and I can apologize only for my delivery, not the content.

And while I’ve missed a thousand other injustices occurring at the same time as this particular one that’s seized my focus, trying to quiet myself with an internal game of “what about [x]?” only engenders a watered-down nihilism that does no one any good. So today, I write from this place, knowing it’s not enough:

For almost two years, we have seen inside children’s skulls, their faces torn back like wallpaper we’ve changed our minds on.

A gray foot sprouting up in a garden of rubble. A shredded corpse lowered with rope and hands from a rooftop—A man was lynched today. Tell me, what does it mean to rest in the cool of a tent with IV fluids when fire rains down at night?

Forgive me, but these things should not be.

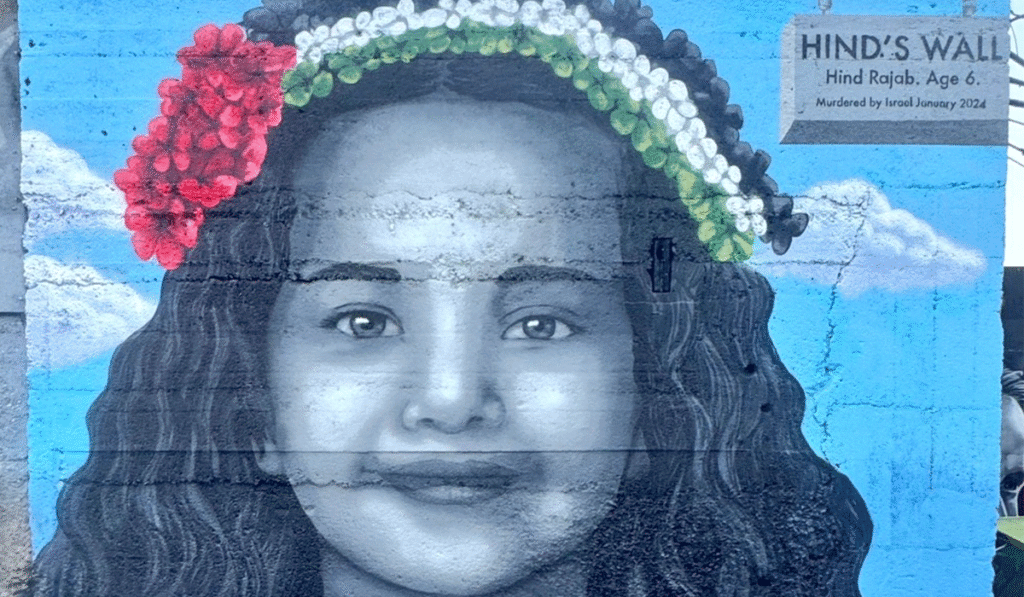

We’ve heard Hind, worried over soiling her dress with blood before over three hundred bullets silenced her body.

What is left to say?

In the beginning—where is the beginning?—I stayed quiet. I adhered to the messages that this was a longstanding dynamic I had no business trying to understand, let alone comment on. Too complicated and deep-rooted. I prayed for the hostages and their families, but did not post online. I did not reach out to friends who were clearly grappling with a sort of devastation they’d only heard stories about before. I am sorry that I didn’t offer what I could have in those early days, which was compassion, even without great understanding. It’s fair to ask how I could publicly lament these dead when I did not publicly lament those?

But as the number of dead Palestinians continued to grow exponentially, and I followed the accounts of journalists in Gaza, sometimes until they were assassinated or evacuated, and read books and listened to interviews and viewed horrific image after image, I made the decision to share stories and posts that resonated with me. To those from my childhood who emailed with concern over my concern with the dead and starving Palestinians in Gaza, I know you respect me. You reached out in good faith. I see you, and I remain unmoved in my conviction, that even if I cannot cite every relevant date or confrontation throughout history, we are witnessing a live-streamed genocide.

The US is helping to fund the forced removal and/or erasure of a people, and that is not new to us. I cannot listen to Ta-Nehisi Coates or Trevor Noah compare Gaza and the West Bank to segregation in the American South and apartheid in South Africa and conclude they’ve been duped by propaganda.

I know that in the big picture, I do not matter. I have my thoughts, humility, and great empathy for those who carry terror and trauma deep in their bodies. Yet I am anchored in my understanding that any person or people with unchecked power can enact indefensible harm against others.

In my lived experience, there is always a point. Maybe an eerily silent march toward erasure obscures the point, or maybe the point is different for all of us, the fulcrum’s balance varying by culture or privilege, religion or age. But allow me this: Whether universal or individual or tied to nation or diaspora, there’s a moment when we sense the hushing of ancillary noise. Our brains no longer register hunger or thirst or the need for sleep, and we realize for the first, or fiftieth time…

There’s a chance the arc won’t bend toward justice here.

If no one steps in, if no miracle prevails, it will be too late. We will have lost too much or too many, and, even if the arc, years from now, begins a glorious justice-ward march, woe to anyone who forgets how mercilessly humans with weapons and power have often decided others’ erasure was their rightful inheritance.

I’m begging you to tell me, what am I missing?

I could list a hundred reasons why my view should be discounted. Maybe it’s mere rumination cosplaying as point of view. Perhaps my justice sensitivity hastily overrides my reasoning. But we have blown past any reasonable point, if such a thing exists. (The dead and traumatized on any side of conflict are always too many.) So I will use my nailbed-sized platform as a writer and mother and human to say I’m okay being wrong on this one. I’ll continue to look to Ta-Nehisi and Amerie, Kiese and Amanda Seales, and other public intellectuals and artists who’ve said what I’ve been too scared to say. And most importantly, Palestinians who have continued to share their lives with us, in hopes we might stop autographing the missiles that obliterate their family trees.

It’s hard to believe my words matter when I don’t know how many more civilians will have died by the time this column is published.

So I’ll just ask one more question: Where is the end?

For two years, we have seen inside these beautiful babies’ skulls, their faces peeled back in a way no surgeon could fix, even if hospitals were still hospitals and not places where people were carried in order to bleed out on the floor.