– – –

I’m flanked by them in most pictures. Perched atop a yellow parking curb in swimsuits and sneakers, we squint and smile for the camera, a mix of frizzy curls and stray hairs haloing our faces. It’s Memorial Day weekend 1986, and we’re minutes away from learning that Hands Across America will not solve the problem of hunger. But in this shot, we’re full of hope and sisterly adventure, and my diaper, bulging beneath my swimsuit, is, well, full.

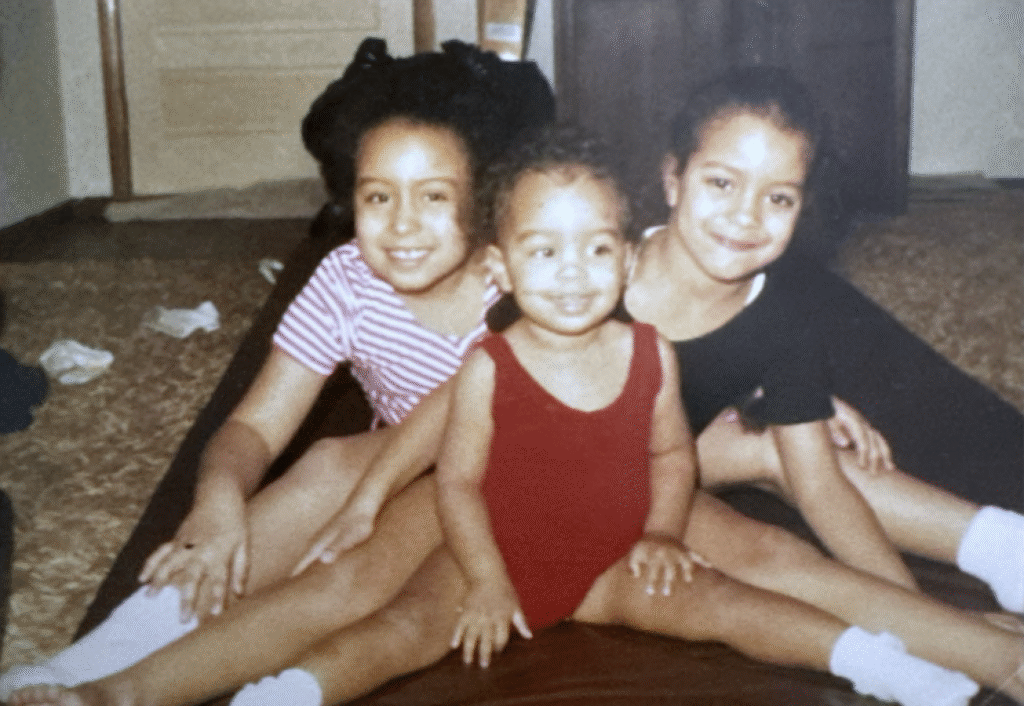

In a photo from the previous year, the three of us pose in leotards, showing off our splits atop a gymnastics mat that’s covering shag carpet. Only Sienna, the middle sister, is a gymnast, but I’ll give it a try soon, and promptly quit. She can keep the hand chalk and stubborn wedgies. But I know exactly why I’m smiling in this picture. I can feel it blooming now in my chest, at forty-two: Safe. Complete. We’re all doing the same thing together.

My sisters, six and a half years and five years older than me, didn’t choose the role-model life. Birth order chose them, and they became my guides for how to be in this world. As the baby of the family, I looked up to them. Took their money. Woke up early to eat the best leftover pizza slices. Okay, and once I hid in Sienna’s closet and took a bite from her school fundraiser chocolate bar, wrapped it back up in foil, and denied it when she discovered the work of my baby teeth. What are you, an archaeologist? You’re just a middle school cheerleader in need of new uniforms. But now, seeing myself as the AuDHD baby of the family, who masked her way through the first forty years of life, my à la carte mimicry of them makes so much sense.

Neurodivergence aside (*laugh track plays), can anyone parse sibling influences in a true or worthy way? I’ll take the bait.

Autumn, the firstborn, embodied a more maternal role. When I started talking later than most kids, trying to say “squirrel” while sucking on my Nuk, or passionately explaining how I loved the clapping of dress shoes across tiled floors, my parents recruited Autumn to translate. She’d listen, make guesses, and give me multiple-choice options, somehow never too tired to try.

When neighbors gifted us a doll from Portugal, she named it “Portugali” and sang lyrics I know by heart:

“I’m Port-u-gali and I love to walk,

Port-u-gali and I love to talk,

Port-u-gali and I love to sing,

Port-u-gali, give me a ring!

Do-do do-do do-deh-do-deh do…”

I sat on our parents’ bed, watching the stiff doll lean right and left in her hand, waiting for the rhyming words I was so good at spotting, mostly just being without any expectations but to giggle when I wanted.

My oldest sister, who skipped two grades in elementary school and left for college at sixteen on scholarship; who answered Jeopardy! questions faster than Alex Trebek could ask them; and read Waiting to Exhale in one night while the rest of us were satisfied watching Angela Bassett start a fire, set the intellectual bar high. When she visited me in DC in my early twenties, she pointed out the NPR building like it was the empty tomb. “How cool is that, Taz?!” I knew the NPR spoofs on SNL better than I knew NPR, but I paid attention, and, a few years later, interned with Michel Martin.

But Autumn also brought a heavy dose of quirk that made my own weirdness okay. We watched Daria together like we were in on a cosmic joke and sang the words to Indigo Girls’ songs as though we knew what fast-fading love could do to a person’s soul. The summer before I was diagnosed as autistic, I intuitively went back to these songs, downloaded them on my phone, and listened as the deep harmonies and storytelling pulled out a chair for me once more.

And when she left for college, and I stayed behind as a rising fifth grader, I wrote her letters with purposely misspelled words, and drew a winged poodle-type creature for her, called it Mini-Habas. Maybe he served as what writer Ann Hood calls the “objective correlative.” The thing that carries the weight of the emotion in a story.

Sienna, born five years and a day before me, acted as a goofy friend who knew how to do everything well. Your TV and VCR acting up? Have Sienna take a look. Not sure what to wear for picture day at school? Ask Sienna if jelly shoes are still in. Feeling a bit drab-headed into senior year? Sienna can give you a bob with a pair of kitchen scissors that would make ’90s icon Monica jealous. Want to imagine breaking the rules by getting drunk off IBC Root Beer? You know who to call. I don’t remember our dynamic ever really shifting, except for the time when I helped Sienna feed her newborn, who arrived seven months after my son. And here’s how you extract the colostrum. Are we even now?

Most of the time, I was thrilled just to watch her work:

Picture us in the ’80s, duh, and we’re standing at the sink of the shag carpet house’s half-bath. Today’s occasion isn’t a fake baptism or Holy Communion with Welch’s and Mikesell’s potato chips. Beloved, today my sister will fit her Barbie’s broken leg with an expertly constructed cast of toilet paper and water, inserting a popsicle stick if she finds a compound fracture.

“I’m going to marry a Hawaiian man and live in Hawaii and be a doctor,” she tells me. I am honored to be a smelly plebeian in earshot of her wisdom.

“Me too. I’m going to marry a Hawaiian man and be a doctor too.” It’s not the first time she’s shared her keys to a good life, but I need to re-emphasize my commitment. She’s the Naomi to my Ruth. The Ren to my Stimpy. The pitcher of water to my frozen juice concentrate. I still cry if Mom is five minutes late picking me up from school. I’m a long way from being able to set a bone across the Pacific.

After Sienna heals the Barbie at the well, I borrow a porcelain doll from Autumn, break its hollow femur, and make no plans to tell her. When she finds the doll, still adorned in its red velvet dress, in perfect condition from the pelvic floor up, I just stare at her, then at the doll, then into the void, hoping for a Christmas miracle. Jesus, be a leg regeneration.

This is how I perceived our bonds as siblings inside the house. I realize, to the outside world, and especially our predominantly white suburb, we looked a lot alike. We functioned as a unit. The Sharp Sisters. As the littlest, the last hurrah, I had to keep up and live up to the good name my sisters made for us. A Sharp sister skipped grades or made the Honor Roll every time or was a class valedictorian. (Imagine my shame when I failed the gifted program test the first time around after interpreting my teacher’s instructions to be “creative” quite literally. It was an IQ test.) She edited the high school paper or won a national essay contest or tried track and field for fun, and clinched a trip to States. She excelled in science or Spanish or both, and performed in the Macy’s Thanksgiving Day parade. These girls turned in their homework, didn’t drink or do drugs, and never worried about parent-teacher conferences. Sometimes they were even asked out by a white classmate who wasn’t afraid of what his parents would say.

Sometimes.

When I couldn’t find a date for the junior prom I’d planned as part of student council (shoutout to Justice Ketanji Brown Jackson, who faced the same predicament), I called Sienna, who was away at college. How humiliating, to be so unlikeable or unattractive that no one would accompany me to a dance for a couple of hours. I cried through my story, embarrassed to admit how I’d failed.

“Taylor, the same exact thing happened to me,” she said.

My sister, the one who’d sent in a picture to Seventeen magazine and was named a semifinalist in some hot mama contest on her first try?

“Yep, the same exact thing, Taz. They think they’re all that.”

That was all I needed.

“Me too,” she’d said this time.

Keep holding on, I’d heard in her voice. Don’t let them take anything else from you. You’re gorgeous, Taz, I’d heard Autumn tell me, often and unsolicited.

There’s a word in The Dictionary of Obscure Sorrows that describes how my sisters have helped ground me in this life:

kenaway (“ken-uh-wey”)

n. the longing to see how other people live their lives when they’re not in public; wishing you could tune into the raw feed of another human existence… if only to give you something to compare your own life against, and figure out whether you’re bizarrely normal or normally bizarre.

I don’t know exactly where I fall on the spectrum of bizarrely normal to normally bizarre, but I lean toward weird no matter what. And I still look at my sisters sometimes and feel the alone-ness of being just a writer, not even a best-selling one, instead of a lawyer or entrepreneur. We aren’t a monolith, it turns out. What did I miss? I ask, or berate, myself on rough days.

Their words, the echoes of “you’re brilliant” and “that’s incredible,” don’t make it all better every time. My sisters have their own lives; they can’t be on call to shore up every place where shame and ableism erode my self-worth. But year after year since 1983, often in moments we didn’t catch on film, they’ve urged me not to turn back from myself. We can see it, they’ve foretold. There’s still more for you here.